In the Rosicrucian Tradition, many have pointed to the message of universal reformation and the healing of humankind’s ills. One of the most important documents in this regard is, of course, the Fama Fraternitatis. In the preface to the 1615 edition of the Fama we are told that after humankind’s fall, the treasure of wisdom once known to earlier generations of Adam had become all but lost. Those who can recognize its signature, however, are able to recover it:

Although now through the sorrowful fall into sin this excellent Jewel [of] Wisdom hath been lost, and meer Darkness and Ignorance is come into the World, yet notwithstanding hath the Lord God sometimes hitherto bestowed, and made manifest the same, to some of his Friends…

…That [s]he, [wisdom], doth shine and give light in darkness, and to be a perfect Medicine of all imperfect Bodies, and to change them into the best Gold, and to cure all Diseases of Men, easing them of all pains and miseries.[1]

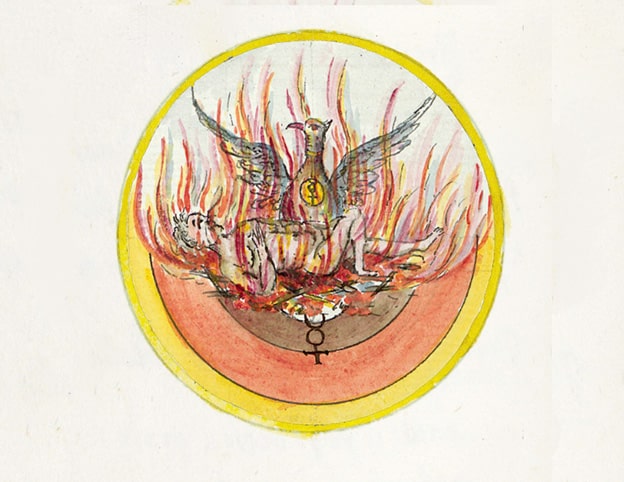

The clue for discovering this “treasure” would seem to lie in that stated above—a jewel, wisdom, a perfect medicine, a cure; one that eases all pains and miseries, and transforms that which is imperfect into pure gold. The symbol invokes imagery of alchemy, yet not just of material alchemy, but something more inner and more spiritual in nature; an alchemy connecting the spiritual, ensouled, and material worlds together as a whole.

Paracelsus is mentioned in the Fama as being important for his reading of the Book M and for his “vocabulary”. In the generations following Paracelsus, his Theophrasta Sancta became an influential doctrine of physis, or natura, that addressed not only subjects of nature and science, but also their interaction within actualized theological realities. Taken as a whole, the mutual interactions of spirit, soul, and body were combined in a “Spherical Art” involving two lights: one light of grace and the other of Nature [2]. Interlacing both the divine and natural worlds, Paracelsus’ doctrine would thus give rise to early conceptions of Christian theosophy—a wisdom of God revealed through both scripture and nature. One that was later influential in Rosicrucian thought.

The origins of theosophy (not the modern movement founded by Helena Blavatsky) can be found in mystic cosmogonies illustrating emanations of the divine descending into the material world; one also revealing spiritual knowledge leading to direct experience (or wisdom) with that source. The term was originally used to describe Christian or Judaic systems for understanding the divine, combined with pious approaches applied to this understanding. In Rosicrucianism, the work of Jacob Boehme often comes to mind when considering theosophy in the Christian context, while other scholars describe theosophy as being akin to, if not synonymous with, Pansophy.[3] To get a better understanding of this influence of theosophy on Rosicrucianism, Paracelsus’ theological, alchemical, and medical doctrines become of particular interest. Yet also, because of the precedent established before him, the work of Marsilio Ficino is significant for influencing Rosicrucian ideas of health and healing as well. Both Paracelsus and Ficino present doctrines illustrating an intersection of nature and faith within a holistic ecosystem.

Many are aware of the duties of a Rosicrucian stated in the Fama Fraternitatis: that they are to perform nothing other than “to heal the sick, and that, gratis”. Some interpret this in a literal, material sense, taking it to mean that a Rosicrucian should do nothing other than to heal sick people physically, with medicine derived from botany or chemistry. The prevailing view of medicine at the time, however, wasn’t that health only focused on the exertion of physical forces on the body, but it was also concerned with the state of one’s soul and spirit. External agencies such as daimones, planets, and elemental spirits were seen as affecting one’s psychic and physical reality as well. Paracelsus and Ficino carried forward classical concepts of vitalism, pneumatism, humourism, as well as the astrological influences of planets on nature, souls, and matter. They combined these influences with their own unique views related to religion, and these theories became doctrinal to much of Western Esotericism following the Renaissance. [4]

Rather than adhering to strict materialist views of healing, it’s thus important to point out that the Rosicrucian concept of healing the sick would likely have involved the physical, psychic, and spiritual states of a person. As we again note how the Fama makes no short mention of Paracelsus (although not of “one of our fraternity”) and, meanwhile, since members of the Manifesto group were noted Paracelsian physicians (particularly Tobias Hess), we’re perhaps just scratching the surface of understanding how these earlier, holistic, magico-religious theosophies were to the Rosicrucian worldview.

Prior to Paracelsus, however, there was Ficino’s Three Books of Life, itself a work synthesizing an understanding of physics, medicine, and health through a multitude of esoteric concepts. These include astrological sympathies, talismans, spiritual influences, the humors, and more. Well-steeped in the natural science and philosophy of his time (which was requisite in the Scholastic education) Ficino wanted to “cure the diseases of ignorance and impiety”[5] through the beneficial effects of spiritus. These occur via the virtues of substances, sounds, and other spiritual forces and their influence over the soul and body.

It is by means of spiritus that good influences from music, odors, colors, foods, and astral influences can be transmitted to the body and bring it into harmony with the soul and physical nature, thus granting it health. [6]

Ficino’s spiritus demonstrates how souls, spirits, and bodies are bound together in a natural cosmic order of mutual confluence. His view also provides a proto-theosophical template that prescribes causes to occult powers emanating from higher divine or natural sources.

But just as mirrors are prepared to receive images by their clear, smooth, glassy nature, so our souls may be prepared for the influx of higher forces, the divinities (numina). Our souls are prepared in that their nature is intellectual, in that they cling to the divine certainties through faith, they move themselves towards them in most ardent love, and they firmly remember them in hope. Finally, if our souls have bodies naturally accommodated to them and carefully readied for them…certain instincts slip down from these deities (superi) into our minds, like vibrations transmitted from the strings of one lyre to another lyre similarly attuned… It is thus [how] marvels, dreams, prophecies and oracles come to us. [7]

Thus the healing of the body begins first by addressing the state of the soul, exposing it to either divine or natural powers. This results in the body moving into harmonious accord with it, much like the relationship between strings on a lyre vibrating in unison. There is a magical component to this as well, as the power of harmonization can not only cause beneficial health but perform miracles.

Ficino is… asserting that our rational souls, appropriately prepared by alienation from the body, can be directly attuned to receive the power of the intelligences beyond the heavens, and that these deities (probably to be identified with Ideas in Nous or Angel) can impart to the highest parts of our soul certain paranormal powers, including the power to perform wonders and to predict the future.[8]

The effect of Ficino’s work Three Books of Life would reverberate throughout the Renaissance, bearing significant influence on not only views of magic and esotericism, but on tomes of magic and occultism in general. A good example is Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa’s Three Books on Occult Philosophy, a work that covers similar ground and was produced some fifty years after Ficino. Ficino’s earlier Three Books seems like an important model for Agrippa.

Returning to Paracelsus, even though he is often portrayed as a lonely figure with limited outside influences, he also learned and studied, and even received a doctorate degree at Ferrara in 1516. It’s thus hard not to consider (even if he did reject much of others’ views) that the priest-physician guise he adopted had been well-established by Ficino some decades before him. It is Paracelsus’ definition, however, that appears most close to the Rosicrucian ideal. With a doctrine adopted as the “Theologicis Theophrasti”[9], Paracelsus may not have been “of our fraternity” but he was certainly an important role model. Several of his doctrines, including the body, soul, and spirit as the tria prima (Salt, Sulphur, and Mercury) are followed within some Rosicrucian circles unto this day. His magico-medical theories, which were combined with Christian and folk leanings, also made him well-accepted by others highly influential to the Rosicrucians. The radical Lutheran pastor Valentin Weigel, for example, theologized many of Paracelsus’ ideas. The theologian Johann Ardnt too endorsed Paracelsian thought as seen in his work describing a mystic union with Christ. Ardnt was also quite influential in the thought of Johannes Valentinus Andreae.[10]

Paracelsus’ own theosophy—which really seems a proper theosophy since his goal is a natural religious philosophy based on biblical and anatomical principles descending from the divine—acknowledges concepts that (even though, again, he often rejects the thoughts of others) correspond with Empedocles’ four elements, the humoral fluids, and other ideas formed around variations of souls and spirits that containing divine, astral, or natural attributes. For Paracelsus, this range spanning heaven, the stars, and the physical world is reflected in humans as well, where we have an elemental body, a sidereal (astral) body, and an immortal body. In an individual, these have a role in the overall constitution of a person’s being, enfolded in a cosmos where the macrocosm of the heavens above corresponds with the microcosm below.

The beginning of the doctrine of this art is the world: it

encompasses the four elements in the way that they reside

in their mother. The intermediate [part of the doctrine] is

the human being: it encompasses the concordance of the

two [the microcosm and macrocosm]. [11]

In Paracelsus’ cosmology, which seems to contain faint traces of neo-Platonism, all things connected to the Earth are considered as feminine. Another dual, or higher, feminine aspect connects to the Earth from above, to the macrocosm. The idea echoes the terrestrial and celestial Aphrodite (Aphrodite Urania and Aphrodite Pandemos) discussed by Plato in his Symposium, discussed later by Ficino. All things masculine, according to Paracelsus, find their place between these two, partially removed from either the macrocosm or the Earth (ie the microcosm). Because of this distinction, Paracelsus sees that males and females must be treated differently for illness or disease since that which is female has its root in the matrix (ie the macrocosm, or cosmos) and that which was male does not. [12]

This offers a glimpse into Paracelsus’ view on the relationship between agents in his theosophy. Souls, bodies, powers, or spirits interact and participate in motion together based on their mutual affinity or sympathy. In his reasoning, the female who receives a seed and nourishes life is bound not only to Earth—such as a seed planted in the earth produces life—but also the matrix (the cosmos) that itself gave birth to the world.

Paracelsus’ cosmic-material synchronization extends into his chemistry. His approach to medicine from plants, for example, comes from a science originating in Galenic and folk practices called phytognomonica. This practice seeks remedies via plants or substances that hold similar, or sympathetic, properties to the thing which needs healing. [13] For example, substances that were yellow would be used to treat ailments connect to the stomach or bile. Leaves in the shape of kidneys might be used for treating these organs in the body. This was also referred to as a Doctrine of Signatures, and seen as a legible legible “book of Nature”. [14] As the famous botanist William Coles once stated, the doctrine existed because “God would have wanted to show men what plants would be useful for.” Similar ideas of medical sympathy are also found behind Paracelsus’ concept of poison, where he considered how a certain substance would affect a like ailment. As Paracelsus is famously quoted as stating, “All things are poison and nothing is without poison; only the dose makes a thing not a poison.”

These principles carry over into the heavenly or religious realm as well. For Paracelsus, Christ was a priest of healing, not only because he could perform miracles, but just for being pious to God.

The honesty of the physician means being as steadfast and truthful as the chosen apostles of Christ, for the physician is not less with God. [And] inasmuch as God is truth, and [God] institutes the physician, how could he make him an old wife or a fool (Daschen)? On the contrary, God must make him in truth. This is the basis of the fourth pillar of medicine. [15]

In addition to this fourth pillar, the first pillar of Paracelsus’s theosophy involves an intimate knowledge of earth and water, the second pillar includes astrology, and the third pillar was alchemy. Paracelsus’ fourth pillar was focused on virtue; on excellence being with God. [16] The Paracelsian doctrine thus included knowledge of all realms—from the Earth, through the substances and stars, all way to the higher powers found in the heavens. Franz Hartmann acknowledged the same in his Life of Paracelsus:

The medicine of Paracelsus deals not merely with the external body of man, which belongs to the world of effects, but more especially with the inner man and with the world of causes, never leaving out of sight the universal presence of the divine cause of all things. His medicine is therefore a holy science, and its practice a sacred mission, such as cannot be understood by those who are godless; neither can divine power be conferred by diplomas and academical degrees. [17]

Within the totality of his medical and theological overview, the work of Paracelsus was likely that which appeared in the minds of the writers of the Manifestos when they referred to “healing” or “curing the sick”. In these terms, healing or curing would ultimately mean bringing a person, a soul, or a body into closer sympathy with the divine powers of the heavens or substances of the natural world. Reaching the highest reality of the spiritual world through grace, or through Nature, would thus be the ultimate goal for the prime “health” or “curing of the ills” for the individual.

The rose is magnificent in its first life, and it is adorned by its taste…. It must rot, and die as such, and be reborn: Only then can you speak of administering its medicinal powers [18]

[1] The Fama Fraternitatis Rosae Crucis, preface. published in 1615, Frankfurt

[2] Joscelyn Godwin, Christopher McIntosh, Donate Pahnke McIntosh. Rosicrucian Trilogy: Modern Translations of the Three Founding Documents. 2016. Weiser p.

[3] Carlos Gilly, Amphitheatrum Sapientiae Aeternae – Schauplatz Der Ewigen Allein Wahren Weisheit: Vollstandiger Reprint Des Erstdrucks Von [hamburg] 1595 Und Des … Einer Aus Dem 1 (Clavis Pansophiae) p.11, transl., Frater Acher

[4] Such older ideas of medicine can be found in Pythagoras, for example, and his views on healing through music and harmony with the planetary spheres. Other doctrines bearing an understanding of the humors and vitalism include the medical works of Galen.

[5] Celenza, Christopher S., “Marsilio Ficino”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/ficino/>

[6] Hankins, James. 2003. Ficino, Avicenna and the Occult Powers of the Rational Soul. In La magia nell’Europa moderna: Tra antica sapienza e filosofia naturale, ed. Fabrizio Meroi and Elisabetta Scapparone, I, 35-52. Atti del convegno (Istituto nazionale di studi sul rinascimento) 23. Florence: Leo S. Olschki. p. 1

[7] Ibid. Hankins. p. 10

[8] Ibid. Hankins. p. 11

[9] See: L Andersson, B., Martin, L., Penman, L. and Weeks, A., n.d. Jacob Böhme And His World. Brill. 2008 & Carlos Gilly, “‘Theophrastia sancta’ – Paracelsianism as religion in conflict with the established churches”, in: Transformation of Paracelsism 1500-1800: Alchemy, Chemistry and Medicin (Glasgow-Symposium 15-19 September 1993), Leiden, Brill, 1998, pp. 151-185.

[10] Andrew Weeks, “Valentin Weigel and Anticlerical Tradition”, in Daphnis Volume 48: Issue 1-2, pp. 140–159. Brill, March 2020

[11] Paracelsus. Weeks, Andrew. (2008). Paracelsus (Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, 1493-1541): Essential theoretical writings. BRILL. p. 623

[12] Ibid. Weeks. pp. 617-719

[13] Consider the Book of Nature in relationship to the Rosicrucians.

The works of Paracelsus also had an influence on the Italian alchemist Giambattista della Porta, who wrote books on the same subject in the mid-to-late 16th century. For example, see: “The maidenhair of

Paracelsus”. (2012, February 23). Plant Talk. URL: https://www.nybg.org/blogs/plant-talk/2012/03/learning/the-maidenhair-of-paracelsus/

[14] Pearce J. M. S. “The Doctrine of Signatures.” Eur Neurol 2008 Epub

[15] Ibid. Weeks. p. 263

[16] Ibid. Weeks. p. 75

[17] Hartmann, Franz. The Life of Philippus Theophrastus Bombast of

Hohenheim, Known by the Name of Paracelsus and the Substance of his

Teachings. 1887. London. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. LTD. p. 167

[18] Ibid. Weeks. p. 17

An interesting read Ian. I have interpreted healing the sick to be less humanocentric and more to do with the healing of Nature – the raising of the lower to the higher, and so the work of the Adept is to raise themselves, and in doing so, they raise (heal) the whole of Nature, albeit just a little, including all those they come into contact with. This relies on one simple assumption – Omnia Sunt Unum – all are one.

This is not too far from what you have written, and I certainly agree on the raising of the Soul (of Nature) to apotheosis.

Thus do we, not for ourselves.

Keep up the good work.

Kasmillos

Thanks for your comment, Kasmillos. In my own path, I’ve come close to an understanding of sympathetic magic involving recognition and piety towards divine beings and the forces of Nature. This, to me, reflects a Hermetic view relating to how the Micocosm is connected to the Macrocosm. I agree about the raising of the Adept and healing a portion of nature, as being part of nature ourselves. That seems to be the place where, through the ages, we have been told where to first look first. But then the reminder is eventually we see that the work comes not of our accord and is a service to others.

I really appreciate seeing a fellow initiate looking at the purpose of our work this way.

& Unum omnia est — one everything is.

Ian

A very thoughtful and in depth article, thank you for it. Part of these realizations may have come from the Cabbalistic concept of “Tikkun” (meaning: repair,restoration, adjustment and so forth). My interpretation is to see it as an ultimate Healing on all levels and thus the goal of “Reunification” is the main purpose of this process. There is a way of reading the account of our Biblical creation as “in the image of Vav” implying that our ultimate destiny is to be a Universal Connector to bring about this Reunification and thus healing to all the Worlds.