A Translation Suitable for Rosicrucians

Several translations of the Emerald Tablet never really spoke to me. There is one version of the Emerald Tablet, however, I treasure for my own path. In this post, I give a full translation of Wilhelm Christoph Kriegsmann’s Emerald Tablet of Hermes, which is highly suited to Rosicrucian students.

The spiritual alchemy I practice is the path of Alois Mailander and J.B Kerning. This entails a specific focus on drawing down divine consciousness and spiritual properties into the human body as a descended thought-light (Mailander’s Baptism of Water), followed by enlivening our ardent internal prayers within the blood as we fully receive the grace from the above and beyond (Mailander’s Baptism of Blood). In this unique path of spiritual alchemy, everything that is experienced from divine grace is made pregnant in the blood in the course of realizing the Holy Spirit in our embodied reality.

Therefore, Kriegsmann’s translation of the Emerald Tablet with its instructions to transcend our consciousness into the higher realms and to “gather the forces, the higher and lower into one” are explicitly practical for anyone interested in Mailander and Kerning’s bodily art of spiritual alchemy.

Therefore, Kriegsmann’s translation of the Emerald Tablet with its instructions to transcend our consciousness into the higher realms and to “gather the forces, the higher and lower into one” are explicitly practical for anyone interested in Mailander and Kerning’s bodily art of spiritual alchemy.

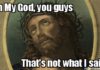

The author, Wilhelm Christoph Kriegsmann (1633-1679) is unfortunately mostly forgotten today. Only Mike A Zuber has given it deserved attention in his recommended in-depth paper titled “Between Alchemy and Pietism Wilhelm Christoph Kriegsmann’s Philological Quest for Ancient Wisdom.”

Out of all of his Theosopher writings, Kriegsmann is best known for his translation of the Emerald Tablet of Hermes, particularly because he believed the original to have been written in Phoenician.

In fact, in his book, Kriegsmann attempted to restore the original lost Phoenician Tablet.

Zuber writes:

Based on his philological skills, Kriegsmann sensed a Semitic original behind the Latin renderings of the famous Tabula Smaragdina. (As Julius Ruska noted after the discovery of the Arabic source, Kriegsmann’s basic intuition had indeed been correct.) Yet according to the young philologist, Hermes was neither Egyptian, as tradition held, nor had his Tabula first been written in Greek, as those who held the writings of Hermes to be forgeries would have it. Rather, the ancient sage was identified as Phoenician and had thus originally composed the Tabula in this lost language

I would only add, that while Kriegsmann is largely considered a Pietist, I alternatively view him as a Rosicrucian in all but name. My reasoning is that although Kriegsmann explored the subject of spiritual alchemy through the Theosopher lens, he also delved into the subject of Hermes in depth, and, coupled with his treatise on the Kabbalah, his bent is far more occult and Hermetic, when viewed alongside key pietistic theologian figures, such as Boehme, Lead and Pordage.

As an example: Keeping true to the Rosicrucian flavor we have come to appreciate, Kriegsmann taught that it was Hermes himself who was the founding father of the German nation. What’s more, Kriegsmann mentions the Rosicrucian Fama manifesto itself in his writings.

To illustrate my point, there is a page in Kriegsmann’s Ḳabalah oder: die wahre und richtige Cabalah where like the later Qabalah of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Kriegsmann offers a table of Kabbalistic correspondences, along with a set of angelic names. His book also includes an angelic alphabet, coupled with magical uses for the spheres of the Tree of Life I’ve not seen before. So, was Kriegsmann a Theosopher or Rosicrucian? You tell me.

Originally, I intended to save this translation for one of my books. But, I am interested in whether or not those of you in our Pansophers community see the same value in this treatise as I do.

Note: I have added a dark red title in brackets to better help highlight Kriegsmann’s revealed version of the Emerald Tablet, because he first provides the standard translations to compare.

Translation of the Emerald Tablet of Hermes

By, Kriegsmann, Wilhelm Christoph[1]

Such as is expressed in the common Latin idiom,

rendered from the Phoenician

The Words of the Secrets of Hermes Tresmegistus[2]

1) True, without lying, certain and most true.

2) What is below is just as what is above, and what is above is just as what is below, for accomplishing the miracles of a single substance.[3]

3) And just as all things have come from one by the contemplation of one,[4] so have all begotten substances come from this one substance, by accommodation.[5]

4) Its father is the sun, its mother the Moon, the wind carried it in its belly, its nurse is the earth.

5) The father of this entire will[6], of the whole cosmos,[7] is this.

6) Its power is whole, if it turns toward the earth.

7) You will divide the earth from fire, the subtle from the dense, delightfully,[8] with great talent.

8) It climbs from the earth into heaven, and again descends to the earth, and receives the power of the things above and below. Thus shall you have the glory of the whole cosmos. So may all darkness flee from you.

9) This is the strong strength of all strength, because it will conquer every subtle substance and will penetrate every solid.

10) Thus has the cosmos been created.

11) Hence, the accommodations will be marvelous, of which this is the manner.

12) Therefore, I am called Hermes Tresmegistus, having three parts of the philosophy of the whole cosmos.

13) What I have said about the action[9] of the Sun has been completed.

Ordinary Summary of the Emerald Tablet

1) It is true, and separate from every wrapping of falsehoods.

2) Whatsoever is below, it is like that which is above. Through this are gained and accomplished the marvels of the work of a single substance.

3) In this way too are all things created from one, by the contemplation of one;[10] thus have all things been made from this one thing through connection.[11]

4) Its father is the Sun, its mother the Moon, the wind carried it in its womb, its nurse is the earth.

5) It is the mother of all perfection.

6) Its power has been completed,[12] if it is changed into earth.

7) The earth separately from fire, the subtle and thin from the thick and dense, and that decently, with modesty and wisdom.

8) It ascends to this point from the earth, to this heaven from the earth, and from heaven it descends back to earth, and it receives the power and effectiveness of things above and below; in this way you will acquire the glory of the whole cosmos; therefore, you will drive out all shadows and blindness.

9) For this <is> the strength winning out[13] over every other strength and power; for it is able to pierce and get under things subtle as well as things dense and hard.

10) By this has this cosmos been founded.

11) And hence its connections are marvelous, and its accomplishments a thing to wonder at; since this is the path through which these marvels are accomplished.

12) And for this reason, they have called me by the name Hermes Tresmegistus, since I have the three parts of the Wisdom and Philosophy of the entire cosmos.

13) My word has been fulfilled, which I have spoken about the work[14] of the sun.

Latin Translation of the Hermetic Tablet

Preserving the idiosyncrasies of the Phoenician context

A Description of the Secrets of Hermes Tresmegistus

(This is the author’s translation based on all his analysis afterwards)

1) Truly, not falsely; certainly and most truly, I say.

2) These things below share forces with those things above, and the one with the other in turn, to produce a single substance, most marvelous of all.

3) And in what way all things have been drawn out from the single word of the One God, so too are all substances continually created from a single substance, by the arrangement of Nature.

4) This <substance>[15] has the Sun as a Father, the Moon as mother; as if it is carried by the air in its womb, it is nursed by the earth.

5) This is the cause of all perfection in things throughout this cosmos.

6) It reaches the highest perfection of its forces if it returns to the ground.

7) Divide into parts the earth after it has experienced the flame, and diminish its density with the most delightful substance of all.

8) Climb, with the utmost shrewdness of your intellect, from the earth into heaven, and thence again descend to the earth, and gather the forces of the higher and lower things into one; thus, gain possession of the glory of the whole cosmos; and so, be no more considered a man of desperate lot.

9) This substance now shall be stronger than strength itself; of course, it will get under bodies, both subtle and solid, by piercing them.

10) And thus, whatsoever the universe contains has been created.

11) Hence do works become marvelous, which are put together in the same way.

12) Thus the name of Hermes Tresmegistus has been lain upon me, because I have been understood to be a Doctor of the three parts of the Wisdom of the cosmos.

13) These are the things which I thought should be indicated concerning the most outstanding work of the Alchemical art.

—

Chapter 3

Now to the Tablet itself. It is called “Emerald,” because it was prepared with emerald stone, and it is believed to have held the words of Hermes inscribed upon it, following the customary system in Hermes’ age of entrusting the arts and sciences to posterity. There is no doubt that it was called in Phoenician and Hebrew לוח ברקת, The Tablet of Emerald, as the divine tablets of stone are named in the works of Holy Moses, **, “The Tablets of Stones,” that is, “stony.” But this is its inscription: “The Words of the Secrets of Hermes Tresmegistus.” These things ought least of all to be passed over, since at the beginning, the tablet’s Phoenician Genius casts off its Latin garb and sets about going forth into the world naked. Of course, the way in which it is said,[17] “the words of the secrets,” is from the East, not from Greek or Latin; and must be explained with the help of Hebrew. The word ** (which, in its meaning of “word” as well as “substance,”[18] produces the greatest honor for holy speech and its kin) sometimes is taken up with a certain unique elegance for literary monuments—that is, public letters, pamphlets, etc. A clear indicator of this usage[19] can be found in Esther, book 9, the final verse, where “royal letters, teaching about the holiday of Purim” (of which mention is made at verse 29) are called **, “Purim words,” that is, “description should be kept, as with the holiday of Purim,”[20] etc. Add to this also the name of “The Books of Chronicles” in the Holy Tome, **, “the words of days,” that is, the monuments encompassing the history of the age, “Day- or Time-Books.”[21] Hence now, the meaning of the inscription on our Tablet will be, A Literary Monument, etc., concerning the Secrets, etc. And in fact, we have written the name Hermes thus: **, Cherem Thlismegiisdos. We shall cite the proofs of this matter below. Next, in the elegant style of Hebrew and its related languages, Hermes begins the tablet: for those declarations concerning business of great importance bring together particles of affirmation, repeating that weighty **.[22]

Tresmegistus preserves the custom, and in order to arouse the greater passion in the reader, promises that he will bring forth great things with that reliable and serious collection[23] of affirmative words (True, without lie, certain, and most true). This done, he begins to write superbly: “What is below is just as what is above, and what is above is just as what is below, for accomplishing the miracles of a single substance.” These words, to the neglect of a truly deep investigation, have thus far been interpreted by the majority of translators, such that you can question without harm,[24] whether or not the things that any number of outstanding philosophers have said in illustrating them, they said not with an understanding of Nature but rather of the Hermetic sayings; but you weep deeply for the abuse of the same things. We shall indicate their true meaning in a few words of Hebrew.

Sometimes, we notice that it happens here that particles indicating likeness, whether inseparable or separated, indicate not only likeness but also agreement or fellowship. Thus, when king Ahab of Israel, as he was going to battle against the king of Syria, sought from king Josaphat of Judea: “Will you go to war with me against Ramoth-Gilead?” Josaphat responded, “Just like you, so am I; just like your people, so are my people; just like your horses, so will be my horses.” (1 Kings 22). That was the same as if he had said, “I will be there for you; my people will be there for your people; finally, my horses will be there for your horses; allies in fighting with the king of Syria.” Rabbis says that these sorts of utterances are **, “for the sake of shortening speech,” since those things would be thus expressed in full: “I will be just as you, and you will be just as me; my people will be just as your people, and your people will be just as my people,” etc. Such is the reciprocity, so to speak, in our Hermetic words. These things, laid out in this particular idiom of the Sacred Tongue, imply not bare likeness to higher and lower things (as it seemed to interpreters), but also agreement and union, which a Son of Hermes should note well. Then this is added to it: “for accomplishing the miracles of a single substance.” It should be remarked that the prefix ﬥ, joined to infinitives, makes up such gerundo-participial phrases, and are explained through the conjunction ut:[25] and that hypallage[26] is also common to Hebrew, as when two substantive words run together, the one which is used as an adjective[27] and should be taken adjectivally comes first (for instance, Psalms 37:2, **, “just as the greenness of a plant,” that is, “just as a plant of greenness,” that is, “just as a green plant”). Therefore, the following words in the tablet, **, produce this meaning: “in order to produce a single substance, most marvelous of all.” Judge now, ye Son of Hermes, about those who want “miracles of a single substance” to mean the gold-producing Philosophers’ Stone.

—

Chapter 4

Light is shed on the next four clauses

Hermes continues: “And just as all substances have come from one by the contemplation of one, so have all begotten substances come from this one substance by accommodation.” It deserves to mentioned here that the Hebrew root from which the term meaning contemplation has derived means, apart from “to contemplate,” also “to pronounce,”[28] so that you can cleverly render the word ** as “speech” or “word”, with this meaning occurring at times in the Holy Scriptures. As for what Hermes said, “they have been begotten,”[29] it has frustrated the talents of many—that is, since those men could not sufficiently grasp how all substances are said to be begotten from one substance by accommodation,[30] etc. Yet the matter is secure: Tresmegistus has used the past tense in place of the present, following an idiosyncrasy of the Phoenicians and Hebrews, who tend to speak thus when there is an indication of not what was or what will be, but what occurs constantly or should occur. By the term “accommodation”, though, none other than the work of Nature is intended. Of course, Nature is order and arrangement,[31] i.e. **, accommodation of causes, just as Aristotle and all the rest of the Philosophers will grant me. It was not unusual for the Phoenicians and Hebrews, however, to use the term ** for indicating the operations of Nature, as one would likely surmise then, since to today’s Rabbis today as well, the natural flowing[32] of the constellations into these lower matters is called **, that is, accommodation, or the order and arrangement of the stars.

Based on these facts, Hermes’ intention cannot fail to emerge quite clearly. What follows, His father is the sun, his mother the Moon, the wind carried it in its own belly, its nurse is the Earth, does not need literal explanation. I only want it to be noted that, by the term ** here, “air” is meant; but then the past-tense “carried,” like “they have been born” above it, must be taken in a present-tense sense. The editor,[33] however, attached to what came before it the following words, This is the father of the entire will, of the whole cosmos, with the word Father exchanged for the term mother;[34] for these things should not be drawn to the earth, since they relate to a marvelous being for Philosophers, which is the father, **, that is, the cause, the origin of all perfection in this universe. Moreover, the pronoun “this” is used erroneously in place of a local particle, for according to the Hebrew-Phoenician ** it is masculine, and has been substituted for the masculine ** and in place of a feminine, because of the carelessness of the translator; “this”,[35] which the word “substance”[36] demanded, has been kept. Its force is whole if it turns towards the earth, says Hermes further down. That is, The virtue of that substance is **, conveyed by nature to the highest degree of perfection, if it (the substance) returns to the ground, etc., and not if its material turns or changes into the material of the earth, as some people put forward rather foolishly.

—

Chapter 5

An inquiry[37] into the meaning of the seventh and eighth etchings

Now we shall have to make do with the common translator, although unwillingly. He writes: You shall separate the Earth from fire, the subtle from the dense, delightfully, with great talent. It climbs from the earth into the sky, and again descends to the earth, and receives the power of the things above and below. I say that “he” writes thus; in fact, I should rather believe anything else than to have faith in those who maintain that Hermes said these things. These utterances contain absolutely nothing Hermetic, nothing Philosophic, nothing indeed either secure or true. Rightly would I ask of the translator, by what[38] fire, then, or by what path should I split fire? Likewise, how would I use the subtle and the dense, delightfully separated with the cunning of Oedipus, for the task of Philosophy? A hard turn, by god, for the greatest Hermes! This man, though he once spoke before the world in the common tongue with the greatest wisdom about the pinnacle of Nature’s secrets, now is forced to have recourse to a translator’s cold language,[39] which would have once incensed and disgusted even the worst of his students in this same business; but from where, you say, did the translator take those words, if Hermes did not pass over them in the actual Phoenician copy of the Tablet?

I shall say honestly what I feel: listen, you who are noble. Both Hermes and his translator are free from blame. The first had written: **, etc. This translates in the way we have said, considering that 1) the term ** should be constructed with the word **; 2) ** is a substantive noun; 3) ** is prefixed to the noun **; 4) the prefix ** in ** circumscribes the adverb, in the particular style of Hebrew; 5) the words ** do not relate to the next clause; 6) finally, the present is indicated by the participles **, **, and **, following the habit of the Holy Language. Indeed, six-hundred of those that were consulted on the dialects of Hebrew and Phoenician would render it hardly differently, when matters are thus compared. On this account,[40] it is fare for the translator to be acquitted of the charge; and there is absolutely no doubt that Hermes, intending to pass down an account of producing Philosophers’ Mercury, deliberately used these words that allow various meanings, that it would not be easy for anyone immediately to set foot into such secrets. Nevertheless, whatever sort of substance it is, we are going to be the first (and this is our weakness)[41] to tease out the true meaning of the Hermetic speech, unless we are completely mistaken. Therefore, the word ** properly indicates such a manner of separation which comes from “distinguishing” or “breaking apart,” etc., and thus is connected to a bare accusative, as is well known. Next, recognize that ** is connected to the term **, in an adjectival sense, in the most elegant Hebrew style, by which a substantive, with the preposition ** or ** coming before it, is employed periphrastically as an adjective and expounded: “earth out of fire,” that is, “aflame,” “having endured fire,” as in Psalms 16.4, **, “their offerings out of blood,” that is, “bloody;” or, using Vatable as translator, “blood-offerings.”[42]

Next, the phrasing ** governs participles,[43] and that of the word ** diminishes the subtle and renders it thin, etc. The word ** properly indicates the rich[44] thickness of the earth, as is clear from 1 Kings 7:46, where the bronze vessels of Solomon are said to be poured **, in the thickness of the earth, that is, in the rich and clay-filled soil, etc. Also, the prefix ** in ** must be treates as **; that is, “Beth of aid,” as the Rabbis says, because in this passage it indicates a helping cause, by virtue of which something comes to be. But as to why the term ** (that is, delightfulness, sweetness) is applied to Hermes,[45] you will almost learn from the words of Rabbi Solomon, according to Master Buxtorf: **, “All the sweetness of fruits is called Devasch.” Consider this, too, that the superlative degree is expressed, in the well-known style of the Hebrew Language, with an abstract noun: just as delightfulness is used here in place of a most delightful thing. Consider, you, what sort it is.

Finally, the words ** should hardly refer to this previous clause—perhaps for the reason that the following participles cannot have the force of a present indicative; for however usual it may be for Hebrew to indicate the present of an indicative with participles, yet this is the reason for our manner of speech: a pronoun must be attached to the first of the participles, so that it typically should be taken as a third person along with the rest. The lack of a pronoun in the Latin is proof that none of that stuff[46] was apparent in the Phoenician context. Thus it happens that we make participles, with their typical force, fit the creator of the Hermetic work, not the material. For this reason now, there is also the fact that we reckon that these words, in the greatness of his talent, should be claimed by another period,[47] so that finally, this sense emerges: “You shall distinguish earth which has undergone fire, thinning out (so to speak) its abundant thickness, for the good of the finest substance of all.

Climbing from earth to the sky by the brilliance of intellect, and again coming down to earth, and joining together the virtues of things above and below.” Thus shall you have the glory of the whole universe. These words should also be put into this next clause—if not in word, then in meaning, for the entire period (ascending by the keenness of talent, etc.) of content[48] about which Hermes wrote, like a sort of summary, encompassing once and for all everything that came before, needs the following: If you ascend by talent, etc., know that you shall have everything that you seek. So, beware! You might think that those words impose the need on you of new operations, of which no mention has been made previously.[49] And so you have what you will on this topic.[50]

—

Chapter 6

A discussion of the ninth, tenth, and eleventh clause

Tresmegistus adds next: So may all darkness flee from you. Darkness, in this passage, is the same thing as ignobility; and the dark, חשכים, are the ignoble, and men of downcast lot, against whom are arrayed the נכבדים, famed and honored men, so-called from כבד, glory, which is the term Hermes wisely sets in opposition[51] to darkness. Because it then reads, This is the strong strength of all strength, because it will conquer every subtle substance and will penetrate every solid one. Thus, one must understand that substance, which is brought out at Nature’s command by the Philosopher from the Philosopher’s material, is the strongest of all (for it is a well-known element of Hebrew style, when a superlative word is indicated by the joining together of cognates and synonyms[52]) of course, since it is able to subjugate and penetrate beings both subtle and dense (יציק, like that which is poured out of metals). Thus was the universe created. How? Pray, speak, Tresmegistus![53] One shall speak on your behalf, for the sake of your students—indeed,[54] your descendants!

It is the author Sanchuniathon, the most ancient Phoenician, and one who (according to the witness of Philo, In Eusebius’ On the Preparation of the Church,[55] book 1, chapter 9, which he wrote entirely about the origins of things) drew from your records. Therefore, he, in Eusebius book 1, established two particular material principles for the founded[56] universe, one of which he calls “blowing” or “spirit,”[57] as though it were active; and the other he calls passive, “gloomy chaos,”[58] that is, following the reading of the Renowned Bochart (towards the end of Tome 2 of The Holy Geography of Canaan); in the Phoenicio-Hebraic dialect, כהות ערב, “evening gloom,” to which he gave the name ἄερος ζοφώδους, “shadowy air.” Here he almost reaches Moses, who at Genesis 1 also makes mention of the Spirit (**, that is, if you translation out of the particularities of the Sacred language according to the meaning of certain things, “a violent breath,” etc.) and of the shadows over the face of the abyss.[59] He adds, ἐκ τῆς ἀυτοῦ συμπλοκῆς τοῦ πνεὐματος ἐγένετο Μὼτ τοῦτο τινές φασιν ἰλὴν, οἱ δι’ὑδατώδους μίξεως σῆψιν—that is, based on its (chaos) intermingling with the Spirit, there emerged Mot (which term, according to the judgment of the Renowned Bochart, comes from the Phoenicio-Hebraic **, with the meaning of “matter,” just like the Arabic **, etc.), which some translate as “mud,” others as “the rot of a watery mixture.” And Sanchuniathon agrees with Holy Moses, who says: the Spirit roused itself (**, that is, just as the Arab Lexicographer, if I am not mistaken, translates wonderfully in the Renowned Hottinger’s Selections,[60] discourse 2, thesis 8 (b), **** shaking, roused by constant movement and shaking, etc.) on the surface of the water. From this mixture, it seemed to him that there was made Πᾶσα σπορὰ κλίσεως καὶ γένεσις ὅλον, “all the seeds of creation and the origin of everything,” etc.

I return now to you, great Hermes, to ask about your opinion concerning the creation of the universe. You wrote in the Tablet about that universal Spirit of the universe, which your Philosophers call their Mercury. But that is the very thing which, at the beginning of things—of seeds, of creatures[61]—brought it forth from the formless mass of ancient Chaos (according to you)[62] and rendered it fit for begetting.

Therefore, you say well—nay, extremely well!—that the world was created thus, that is, all things began through this universal principal,[63] by the approach of this universal Spirit to the special seeds of each being. You go on wisely: Hence, the accommodations will be marvelous; the manner of which is as follows, that is, according to your Language: **, hence, those natural operations become things worthy of wonder, (whether they come about through nature alone, or also through artificial arrangements[64]) which are established for this type of created universe. This is the meaning of the words: Whenever the word “accommodations” can be used both for the operations of Nature (being, so to speak, purely natural) and for other things which arise through nature because of the former artificial arrangement, the future “they will” is in fact used in place of the present.

Following a not uncommon habit of Hebrew, the present appears in general statements **, as Rabbi Aben Esra says; that is, in the speech of carrying out what will be, and a phrase similar to it, **, which occurs at Genesis 31:35: **, “I am dealt with in the manner of women,” etc. To there has Hermes pursued his secrets.

—

Chapter 7

The meaning of the remaining two clauses explained

There follows a nominal subscription of such a sort: Therefore I have been called Hermes Tresmegistus, having three parts of the Philosophy of the whole cosmos. It has dashed many men of outstanding intellect upon its waves and rocks, some of whom, given how they measured the three parts of philosophy with a division of substances into Animals, Vegetables, and Minerals, began to suspect that the substance of the Philosopher’s Stone should be sought in those kingdoms, as they call them, by a son of Hermes; everyone else has misused the authority of the famed Count Trevisan in particular, because they thought that the particle “therefore” should be applied to what came before, and they did not sufficiently understand how the construction of the Philosopher’s Stone produced Hermes Tresmegistus.

They divided into various opinions on the subject of the Tablet—and they were combined not seldom with a great loss of truth. Moreover, in order for such Syrtes[65] to learn in the future how to avoid those that cherish truth, they should note before all else that the particle “therefore”[66] in the Latin translation has its accent on the penult, not on the antepenult; and thus it is made up of two things: an adverb of similarity and a conjunction, (which) look toward the substantive word **; for thus do the words of Hermes have it, straight from the source: **. Moreover, there is an exceedingly elegant ellipsis of the causal conjunction ** or ** which comes between.

Once this has been recognized, the sense will be clear: And so I have been called Hermes Thlismechüstos (Tresmegistus) because I have the three parts of the Wisdom of the whole universe. But concerning those three parts of Wisdom, one must not judge following the division of bodies into **, as the Rabbis call it—that is, having breath possessing movement, and still,[67] or Mineral. Rather, one must rightly hold onto <the lesson> from chapter 2 book 3 of Aristotle’s Metaphysics, combined with chapter 6 book 12—that all Philosophy is divided into three parts according to the number of substances. The First of these treats with immoveable substance, and is called Theology or Metaphysics; Second Physics pays heed,[68] and is engaged with moveable, corruptible substance; finally, the third, dealing with moveable, incorruptible substance, is called Astrology.

The deviser of these three parts of Philosophy, Hermes, since he was deemed to be divinely decorated by them, with the intervention of supernatural revelations, began to be called by the majority of the Phoenicians **, Hermes of the three revelations, that is, for whom three revelations divinely befell. When the Greeks heard this, being constantly given over to foolishness by just moving names from Phoenician into Greek, immediately put their hands to the title and, corrupting it because of a certain similarity with Attic words, produced from Thilismechüsdos (just as utterances doubtless are spoken, with the pronunciation of Phoenician words departing somewhat from Hebrew), so that it became τρισμέγιστος, with the ** turned as usual into a Greek “P.” Anyone person will be able, by their own efforts, to gather the rest from what has been said. Finally, Hermes concludes in this way: “It has been completed, what I have said about the operation of the sun.” But what has Hermes[69] said? Rather, the Translator, apart from, perhaps, his thought process. Of course, in the ancient Phoenician copy of the tablet, there was **, which was immediately rendered by the translator: concerning the operation of the Sun. But oh, what a fine operation of the sun. Indeed, I am hardly convinced that that word is, **, “sun;” but that is thus used here, a fact I do not deny. What might be indicated by that phrase apart from “sun,” you ask us? I shall say it in a word: The art of alchemy because its name comes from the same root as the name for the Sun (see Our Conjectures on Tacitus’ Germania), and that with the form of the word **; then why should it be strange if translators, thinking too little about the etymology of Alchemy, corrupted it to “Sun.” When they have translated it more correctly: “The things have been finished, which I had taken up to say about the work of Alchemy.” How the sons of Hermes translate (as though I were advising them) seems, based on the circumstances, to lie with both the Doctor and his students. But the term ** is properly used concerning the most outstanding work of Alchemy just like par excellence;[70] so also with the Greek phrase “Alchemical making;” and at times with the term “maker of Alchemy” (as testified to by Master Reinesius, Varius Lectures, book 11, chapter 5), etc.

—

Chapter 8

The subject of the tablet is put together

I have briefly discussed the text of the Hermetic Tablet; it should remain to lay something out about what pertains to the matter itself. But since great men demand care for their own business, I would be thought rash if I, in my youth, undertook to lecture about such challenging topics. The story goes that the tablet teaches about the Philosophers’ Stone, which creates gold and silver. So the most famous of the Alchemists think; but the author of Fame remitted to the brothers of the Rosy Cross, a man renowned to us, accuses these men of falsehood, writing: “So too must the same Tablet teach the Method of the Philosophical Stone, which Paracelsus claims no differently in Archidoxis, but rather the text itself proves it. Then he says that, as regards this knowledge, the man called Tresmegistus. Having the three parts of Philosophy; who wants, however, to believe that either the making or knowledge of the stone creates Tresmegistus, having the three parts of Philosophy?

Then it would be that one of them would be so completely blinded by shine of pay that he knew a bit more neither of God than other things, and gold would be regarded as the highest good. Indeed, men’s knowledge is much more important than the knowledge of the stone,” etc. Moreover, that tablet teaches about the operation of the Sun and the influence of the ethereal Spirit, as the words clearly indicate. And previously, in Hermes’ day, it was not necessary to call metals by the names of the planets, etc. In sum, it teaches that all creation comes from spirit, all natural motion and change comes through Spirit; for Spirit exists before the body. “Thus, that they call themselves Hermetic philosophers, do not know what ‘Hermetic’ is, and so, that they dub “Hermetic,” know how to demonstrate with a letter, or to prove what is known from Hermes; without which, one person would foolishly enough imagine one thing, another another.” So he says, the meaning of which lies in the hands of the Reader.

Lest we grant more to the Tablet than is fair, or diminish the glory of its subject in any way, we at least allow to Hermes that the language explicitly concerning none of the gold- / silver-producing stones belong to Gebrus, Lullius, Trevisanus, Valentinus, Parecelsus, etc.; such that, in the opinion of Garland and others, by “lower things,” he meant the body; by “higher things,” the soul; by “miracles of a single substance,” the virtue of a perfect Stone; by “Sun,” gold; by “Moon,” silver; by “wind,” Mercury, by “nurse,” yeast; etc. But we offer a nautical[71] interpretation for those who believe that the tablet absolutely must have been graven by the hands of Alchemists, and that because it does not treat with the gold-producing Stone, etc. Let it not happen that a son of Hermes advance to such a point of rashness. Moreover, in order for my reader to grasp in a few words what we ourselves feel about the subject at last, I follow a number of Philosophers of outstanding talent and say:

The Emerald Tablet deals with the UNIVERSAL MERCURY OF PHILOSOPHERS, which strips both thin and dense bodies by penetrating them, drawing that as pay for its efforts, if you will. By That it never cease to exist, since it exists everywhere…Concerning, of course, the fifth Universal essence of the four elements, for which today the things below and the things above join hands in fellowship, bringing it to light as though it had to be advanced at the command of Nature,

Sun, the source of FIRE, seed;

Moon, lady of WATER, seed;[72]

Wind, the host of the AIR, menses;

Earth, the prince of the LAND, milk

Through this the plans bloom, and living creatures draw life, and minerals grow, and the heavens give birth, and Nature, at last, is nature. You have, my friends, what I think about the Tablet.

Copyright: Samuel Robinson

Footnotes:

[1] https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/8884/28/0/?fbclid=IwAR2zhdPJRIL2NZ6KBlwhHX73ARCjBcLHim763SkjObPjIuGQahNYx9Qb_xs

[2] Written as Trismegistus in the text, but more often today called Tresmegistus (“Thrice-greatest”)

[3] ad perpetranda miracula rei unius. The grammar of this selection is clear, but the meaning of unius rei is a little confusing. Res literally means “thing,” and it can be used in as many (if not more) situations as the English word “thing.” I have translated it as “substance” throughout.

[4] Just unius; maybe rei has fallen out in ellipsis (“from one thought of one substance”) or maybe a substantive person (“from one person’s one thought”). Maybe God (“the One”)?

[5] adaptatione, literally, the act of “fitting” or “adjusting” something to something else.

[6] thelesmi, seems to be a neologism, from the Greek root θελ- (“wish” “will”), turned into an abstract noun by the suffix –ismus (exactly like the English “–ism”).

[7] mundi, often translated “world” (compare Spanish mundo) but technically refers to the entire universe, or all of created existence.

[8] suaviter, the exact connotation of “pleasant” or “delightful” is unclear here.

[9] operatio, literally “working” or “labor” (the act of work), but in Christian authors it can mean “charity” or “beneficence” – “What I have said about the beneficence of the Sun…” It can also mean “religious performance” or “offering” (maybe verging upon “rite”), so there are a lot of possible connotations to tease through.

[10] See note 2 above. per considerationem unius could refer to the thing referenced by unius performing the act of contemplation (which seems to match the first translation), but it could also refer to someone else contemplating the thing referenced by unius.

[11] conjunctio, “joining together”

[12] perfecta, “done completely”

[13] palmam praeripiens, literally, “snatching the palm <of victory> first”

[14] opus, similar to operatio, but often refers to the thing produced than the act of production.

[15] ea, without any noun; feminine nominative singular, probably modifying an understood res.

[16] incisa comes from incido, meaning “to cut into,” but its perfect passive participle can be used as a noun meaning “division,” “section,” or “clause” (here, it refers to each of the numbered statements on the Tablet).

[17] loquendi forma, literally, “the shape of speaking.”

[18] rei, see note 2. I

[19] Cuius rei luculentum indicium, “a bright pointer of which thing,” rei not referring to “substance” here as it does in note 2; this is its regular usage in Latin, and it will appear occasionally throughout the text.

[20] Beschreibung wie es mit dem Feste Purim gehalten werden soll

[21] Tag- oder Zeit-Bücher.

[22] I think this is Hebrew for “Amen”

[23] συναθροισμῶ, “a collection,” “a union.”

[24] ut non injuria ambigere possis, “so that you can doubt not with damage,” exact meaning of iniuria here unclear

[25] ut in Latin means “as” with an indicative mood verb, but with a subjunctive (like we see here), it indicates purpose: “in order to <do something>,” or just “to <do something”

[26] This is a rhetorical device, from the Greek word ὑπαλλαγή, “exchange,” “interchange.” It refers to an adjective modifying the ‘wrong’ noun in a sentence; e.g., “She let out a lonely sigh,” where “lonely” properly describes the girl and not the sigh. The author provides his own example in the next sentence.

[27] epitheti, from Greek ἐπίθετος, which means “additional,” but in the context of grammar means “adjectival.”

[28] Meditari and eloqui

[29] natae fuerunt

[30] quei omnes res natae ab una re dicantur adaptione. This is very strange sentence: quei is not a normal Latin form, appearing instead to be an archaic nominative plural in agreement with omnes res natae (literally, “all which born things”) or perhaps an unorthodox spelling for quī, an adverb formed from the relative pronoun meaning “how”; dicantur could come from a first conjugation verb meaning “to dedicate,” or a more common third conjugation verb meaning “to say”; and adaptione seems to be a typo for adaptatione, “accommodation.” The most logical translation is the one I have provided (the scholars do not understand how all things can be born from one thing), but it still is a little confusing.

[31] dispositio, literally, “distribution” or “arrangement,” from dispono, meaning “to place around” or “to put in difference places,” but here it seems to be emphasizing the orderly arrangement of scheme of the universe.

[32] Influxus literally means “flowing in,” but there is one instance in the dictionary where it is paired with stellarum and means “influence” : stellarum influxus, “the influence of the stars.”

[33] Paraphrastes, “one who makes a paraphrasis / paraphrase / summary.”

[34] in nomen matrem versā, could also be translated “turned into the term mother.”

[35] This whole section is about the grammatical gender of the various word; the Emerald Tablet uses hic, a masculine form, when it should have used haec, the feminine form.

[36] τὸ res, literally, “the thing,” but mixing Greek and Latin suggest the author had something particular in mind; it seems like he wants to emphasize that he is not talking about res in its literal sense (“thing,” “substance”), but about res the word, with a particular grammatical gender.

[37] inquiritur, literally, “it is asked into.”

[38] quoniam means “since,” but it seems like a typo for quonam, “who,” “what,” which is how I’ve translated it.

[39] interpretis frigore sermoni adsuescere, “to have recourse to language with the coldness of a translator,” the exact interplay of the words is confusing, but the sense is straightforward.

[40] quo nomine, literally, “by which name.”

[41] quae nostra est tenuitas, literally, “which is our slenderness.” This word can be negative (“smallness,” “insignificance,” “poverty”) or positive (“fineness,” “minuteness”), and it is unclear whether the author is bragging or (as seems more likely) trying to affect humility.

[42] A distinction between ex sanguine, sanguinea, and sanguinarius. The last two are roughly synonymous, but sanguinarius is less common.

[43] praesens est participiis; praesens is also used of the grammatical present tense, so this might read something like “it is present with participles,” although what that means is unclear.

[44] pingem, likely a typo for pinguem, “fat,” “rich,” “fertile.”

[45] voce Hermeti appelletur, literally, “it is named to Hermes with the term.” I have never before encountered an impersonal passive with appello, “to call,” “to name,” but this seems like the sense of the passage.

[46] eius rei nihil, “nothing of that thing.” I believe res is referring to all the grammatical discussions the author has just engaged in regarding pronouns.

[47] periodo, which can also mean “sentence;” I think it’s used here to mean “clause,” like incisum.

[48] rerum, it seems to not mean “substance” here.

[49] Very strange grammar, but this seems like the most sensible translation

[50] Atque haec de his Tibi habeto, literally, “And have for yourself these things about these things.”

[51] ἀντιθέτην, “opposed,” “set against,” “opposite”

[52] coniugatorum

[53] Tresmegisti is in the genitive case, which should not normally be used with a plain dic—literally, it says something like “Speak of Tresmegistus!” Possibly a typo for Tresmegiste, the vocative, as I have translated it.

[54] quidam, “a certain man,” “certain men” in the text (“a certain man will speak for the sake of your students, for your descendants”), but it would make more sense if it were a typo for quidem, “indeed.” This entire section is rather obscure.

[55] ap<ud> Euseb<ii> de praep<aratione> Evang<elica>, my interpretation of the abbreviations.

[56] conditi, can also mean “hidden”

[57] πνόην sive πνεῦμα. Both literally mean “blast” or “blowing” (like the wind), but are more often used of one’s breath.

[58] χάος ἐρεβώδες

[59] super faciem abiissi. The literal meaning here is unclear; believe that abiissi is an unorthodox spelling of abyssi, which means “a deep chasm,” but in Christian authors becomes an epithet for Hell (the abyss).

[60] analecta

[61] rerum seminium creaturarum, no punctuation or conjunctions, but sometimes authors will do that for rhetorical flourish.

[62] te auctore, literally, “with you as author”

[63] per hoc universum, literally, “through this whole thing”

[64] artis dispositiones, literally, “arrangements of art”

[65] What this means is unclear; the Gulf of Sirte (Syrtis in antiquity) could refer one of two bodies of water on the North African Mediterranean, so Syrtes could refer to both bodies, or perhaps to the people that live there.

[66] itaque

[67] animatum, vegetans, ac silens

[68] audit, literally, “hears”

[69] dixi Hermes, literally, “I, Hermes, have said.” The author is either echoing the dixi from the citation, or this is a typo for dixit. The meaning is not appreciably different (unless the author is calling himself Hermes), so I have translated it as dixit.

[70] κατʹ ἐξοχήν, literally, “in accordance with pre-eminence,” “premiere”

[71] neuticam, I have translated it as an unorthodox spelling for neutiquam

[72] Semen vs. sperma