In the first edition of our book, Alchemically Stoned: The Psychedelic Secret of Freemasonry, we posed the following question after exploring Count Alessandro di Cagliostro’s use of an entheogenic elixir of Acacia in his Egyptian Rite of Freemasonry:

“Was the sprig of Acacia added to Masonic ritual on account of its DMT content, or did certain Alchemically-inclined Freemasons [such as Cagliostro] who were privy to the Acacia’s entheogenic mysteries take it upon themselves to interpret and apply it in that manner?”[1]

Indeed, many species of Acacia are known to be rich sources of the powerful psychedelic compound dimethyltryptamine or DMT, an entheogen with a long history of ceremonial use among various tribes in South America, the Caribbean, and elsewhere.

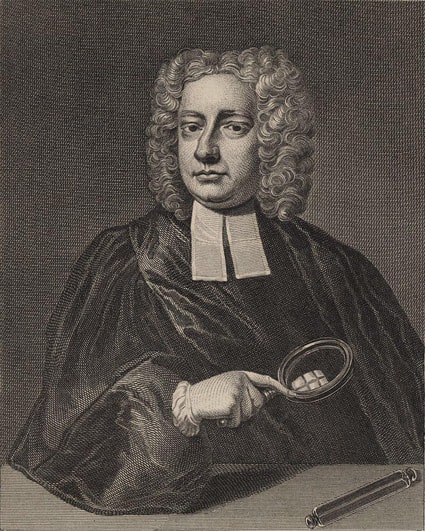

Recent evidence appearing in the forthcoming second edition of our book suggests that entheogenic alchemical elixirs may have been at the heart of Freemasonry since the 1720s, merely a few years following the fraternity’s inception in 1717. For, in 1719, alchemist, philosopher, clergyman, and engineer, John Theophilus Desaguliers (1683-1744), was elected third Grand Master of the Premier Grand Lodge in London.

Before Desaguliers’ election, there was no mention of a sprig of Acacia anywhere in the rituals of Freemasonry. Instead, the earliest rituals make reference only to a sprig of Cassia, a cinnamon-like plant native to China.[2] However, following Desaguliers’ stint as Grand Master, as is evidenced in the various exposures of the era, Cassia became Acacia in virtually every Lodge in Europe. As Desaguliers was instrumental in rewriting the Master Mason degree in the 1720s[3], it is likely that he was behind this particular alteration as well. If so, then we would need to be able to demonstrate that Desaguliers had an invested interest in and working knowledge of entheogenic plants. Tellingly, Desaguliers was a Fellow of the Royal Society where he served as research assistant to fellow alchemist and scientist, Sir Isaac Newton. As we know from Boyle’s Wish List, the Royal Society was no stranger to psychoactive drugs.

Before Desaguliers’ election, there was no mention of a sprig of Acacia anywhere in the rituals of Freemasonry. Instead, the earliest rituals make reference only to a sprig of Cassia, a cinnamon-like plant native to China.[2] However, following Desaguliers’ stint as Grand Master, as is evidenced in the various exposures of the era, Cassia became Acacia in virtually every Lodge in Europe. As Desaguliers was instrumental in rewriting the Master Mason degree in the 1720s[3], it is likely that he was behind this particular alteration as well. If so, then we would need to be able to demonstrate that Desaguliers had an invested interest in and working knowledge of entheogenic plants. Tellingly, Desaguliers was a Fellow of the Royal Society where he served as research assistant to fellow alchemist and scientist, Sir Isaac Newton. As we know from Boyle’s Wish List, the Royal Society was no stranger to psychoactive drugs.

Robert Boyle is often recalled today as the father of modern chemistry. In addition to his earth-moving theory that elements constituted “perfectly unmingled bodies” which were constantly colliding and in motion, Boyle is perhaps best known for Boyle’s Law, a physical law describing the inversely proportional relationship between the absolute pressure and volume of a gas, when the temperature is kept constant in a closed system. A founder of the Royal Society, which was created for the purpose of promoting the scientific method, Boyle was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1663 and was eventually elected its President in 1680 – although he declined the position. However, what Boyle and the Royal Society are not remembered for are their fascination and pursuit of “hallucinogenic drugs.”

In fact, in 1670 and later in 1689, natural philosopher, architect, and polymath, Robert Hooke FRS, whom Boyle recommended be the Curator of Experiments at the Royal Society in 1662, delivered two lectures to the Royal Society on the psychoactive and physical effects of hashish. As Dr. David Harrison points out in his study, The Genesis of Freemasonry, “[Hooke’s] friend, sea captain Robert Knox, brought back from his travels a ‘strange intoxicating herb like hemp’ from one of his trips and gave it to Sir Isaac Newton’s rival, Robert Hooke.”

“It is a certain plant which grows very common in India… Tis call’d, by the Moors, Gange; by the Chingalese Comsa; and by the Portugals, Bangue.

The Dose of it is about as much as may fill a common Tobacco-Pipe, the Leaves and Seeds being dried first, and pretty finely powdered.

[It taketh] away the Memory and Understanding; so that the Patient understands not, nor remembereth any Thing that he seeth, heareth, or doth, in that Extasie… After a little Time he falls asleep, and sleepeth very soundly and quietly; and when he wakes he finds himself mightily refresh’d, and exceeding hungry.”[4]

Moreover, in 2010, the Royal Society put on display Boyle’s Wish List, a list of items Robert Boyle wanted to acquire for the Society to study. To our surprise, among those items were listed:

“Potent Druggs to alter or Exalt Imagination…procure innocent sleep [and] Pleasing Dreams…exemplify’d by the Egyptian Electuary and by the Fungus mentioned by the French Author – [namely,] hallucinogenic drugs.”[5]

Chris Bennett explains in his magnum opus Liber 420: Cannabis, Magickal Herbs and the Occult,

“[Egyptian Electuary is] a likely reference to Egyptian hashish electuaries such as majoon or dawamesk. The…‘Fungus mentioned by the French Author’ may allude to a reference to an agaric mushroom in a possible entheogenic context recorded by Rabelais…‘Agaric’ is a species of mushroom that includes known psychoactive strains, such as Fly Agaric.”[6]

For, as Professor Dan Merkur, a faculty member of the Toronto Institute for Contemporary Psychoanalysis and visiting scholar in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto, wrote in his 2014 article, Drugs and the Occult,

“Robert Boyle adopted Ashmole’s trope, stating it was ‘possible or lawful…by the help of a red powder which is but corporeal and even an inanimate thing to acquire communion with incorporeal spirits.’”

In [Ashmole,] for purposes of mystification, [the powder] is additionally called the red stone.”[7]

“[The] stone,” Merkur added further, “was psychoactive.” Similarly, in The Origins of Tantra, Drugs and Western Occultism (1990), O.T.O. ritual discloser, Francis King, said of Ashmole: “I think [he refers] to processes designed to extract hallucinogens from plant and animal substances.” Thus, we know that Robert Boyle and the Royal Society had been investigating hallucinogenic drugs virtually since the latter’s inception.

Recall that, as the biographer of Elizabethan magus, Dr. John Dee, Ashmole was the first to publish the mysterious account of the alchemist, Sir Edward Kelley, who became Dee’s personal seer in a series of angelic communications following his discovery of a magical red powder. With his sharp, rational mind, like Merkur and King after him, Boyle saw straight through the mystification of his Fellow, Ashmole, and perceived immediately that what he and Kelley were on about must have been some sort of psychotropic drug. It is from this background which the sprig of Acacia crept into Freemasonry.

Contemporaneous with Desaguliers’ reworking of the Master Mason degree, in December of 1723, a Masonic exposure appeared in the London-based newspaper, The Post Boy, that remains one of the more curious examples of the literary genre. Its flowery, alchemical language is consistent with the chemical pursuits of Desaguliers et al. Moreover, it makes reference to a “Grand Elixir,” possibly an elixir of Acacia, as part of the ne plus ultra of Masonic attainment. In his paper for Heredom Vol. 7, The Post Boy Sham Exposure of 1723, Brent S. Morris, the editor for the Scottish Rite Journal, concluded that The Post Boy exposure was fraudulent. However, with all due respect to our Illustrious Brother, for reasons to be explained below, we are not so quick to dismiss its admittedly curious contents.

The final of the forty-two questions and answers posed in the Post Boy exposure contains the following exchange.

“Q. What qualifies a Man for the Seventh Order [of Masonry]?

A> Thefe five Things. Firft, Conqueft over Nature. Secondly, the Compofition of the Grand Elixir. Thirdly, The Maftery of the great Work. Fourthly, the Chaining of the Golden Dragon. Fifthly, the Enjoyment of the Silver Lady, & c.”[8]

In the paragraphs which follow, we’ll attempt unpack some of these cryptic points and see how, if at all, they might relate to the psychedelic pursuits of the Royal Society – and to the sprig of Acacia in Freemasonry.

The alchemist is said to work with Nature, gently assisting in Her processes, rather than dominating and controlling Her. Therefore, the “Conqueft over Nature” is likely an allusion to the conquest over one’s own lower nature; to the subduing of the passions, as it is said in Freemasonry. The “Compofition of the Grand Elixir,” we’ll return to below. “Maftery of the great Work,” conversely, is analogous to the perfection of the ashlar in Freemasonry and to the production of the philosopher’s stone in alchemy. These are straight forward enough. The others will require more explication.

Before we get to “the Compofition of the Grand Elixir,” the last two qualifications, the “Chaining of the Golden Dragon” and the “Enjoyment of the Silver Lady,” require some explanation. In alchemy, special emphasis is laid upon metals and their transmutation into silver and gold, which were seen as the perfection of the metals. Unlike the so-called “base metals,” silver and gold do not corrode, rust, or patinize. The motif of the transmutation of base metals into silver and gold was further extended into the realm of spiritual metaphor, where it became an analogy for the illumination or enlightenment of the alchemist himself. Further, silver and gold were treated as complimentary opposites, likened to the moon and the sun, respectively; to a silvery, lunar queen and a golden, solar king, engaged in a perpetual hierogamy or hieros gamos. As the alchemist and Freemason Count Alessandro di Cagliostro wrote in the rituals of his Egyptian Rite, “It is thus that you may bring about the marriage of the Sun and Moon.”[9]

Peter Levenda rightly associates this sacred marriage ritual with that of another pair of commplimentary opposites: Shiva and Shakti. Indeed, like China, long before Western Europe, India was possessed of its own rich alchemical tradition, which understandably left discernable marks on Western alchemy. In his remarkable book, The Tantric Alchemist: Thomas Vaughan and the Indian Tantric Tradition[10], Levenda explains,

“The Indian influences had been watered down considerably by the time alchemy had reached seventeenth century England via the trade routes that existed between China, India, Central Asia, and the Levant over the course of some two thousand years or more. But where the cultural content of Indian alchemy would have been diluted with the passage of time and geographical distance, the essential practical content would have been preserved, much the same way algebra was taught in American secondary schools is empty of its Arab content, even though it had its origin in the Middle East…”[11]

Intimately connected with Ayurveda and Tantric yoga, Indian alchemy, like Western alchemy, was centered upon a coniunctio or union of opposites: god with goddess, sun with moon, linga with yoni, etc.

“In the alchemical context, Shiva represents the Moon and Shakti, the Sun.

The waning of the Moon is said to represent the depletion of Shiva’s seed, while the waxing phase represents his accumulation of seed. …To the Tantric alchemists, the Sun – Shakti – depletes the seed of the Moon, Shiva.

In biological terms, Shiva resides in the cranial vault, asleep. Shakti, as the coiled serpent Kundalini, rests at the level of the lowest cakra at the base of the spine. …The various practices known as Kundalini yoga, however, are designed to…coax [Shakti’s] subtle essence to rise up the spinal column (or its subtle equivalent, the susumna pillar) to the level of the cranial vault…as the serpent goddess Kundalini mates with Shiva…”[12]

It is in this context which the “Chaining of the Golden Dragon” and the “Enjoyment of the Silver Lady” should be understood. Whereas in Tantric alchemy, Shiva represented the moon and Kundalini Shakti, the sun, in Western alchemy, it is the Rex who represents the sun and the Regina, the moon. Recall when Levenda said that “where the cultural content of Indian alchemy would have been diluted with the passage of time and geographical distance, the essential practical content would have been preserved.” While the essential practical content of Tantric alchemy has been preserved in the West, the particular cultural content, e.g., Shiva and Shakti, has virtually vanished. Ergo, the “Chaining of the Golden Dragon” is a masculine analogue to the coaxing of the solar serpent goddess, Kundalini Shakti, from Her resting place, and the “Enjoyment of the Silver Lady,” a feminine analogue to the sexual union which takes place in the lunar cranial vault, once associated with the god, Shiva, but here transformed into the “Silver Lady.” As the Swiss psychiatrist, C.G. Jung, wrote in his monumental alchemy study, Mysterium Coniunctionis, enantiodromia, the exchange of attributes between two opposites, is actually quite common in alchemical literature.[13] Cf. the red lion turned white with the gluten or tears of the eagle, and the white eagle turned red with the blood of the lion, etc. etc.

The choice of the cranial vault as the dwelling place of Shiva is interesting. Aside from the injunction in Liber Platonis that the true vas hermeticum, the sacred vessel wherein the alchemical transmutation is said to take place, is the humal skull, also located in the “cranial vault” is the pineal gland, suggested by Dr. Rick Strassman in his book, DMT: The Spirit Molecule, to be the possible source for endogenous DMT production.[14] Other sources point to the lungs as the possible place of origin, lending credence to the notion that yogic techniques such as pranayama or breathing exercises may occasion psychedelic, mystical experiences. In any case, the implication is that the stone of the philosophers may be produced both within and without the human organism; that is, there are internal and an external forms of alchemy.

In China, internal alchemy is referred to as neidan, while external alchemy is referred to as waidan. Closely aligned with the practices of qi-gong and tai chi, neidan concerns the manipulation of the nervous, libmic, and endocrine systems for the production of an internal essence or elixir, not unlike the production of Shiva’s lunar seed in Kundalini yoga. Waidan, on the other hand, which is more closely related to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), is identical with laboratory alchemy and concerns, through the manipulation of minerals, metals, plants, fungi, insects, and animals, the production of the same elixir vitae that is common to all true forms of alchemy.[15]

As one might expect, various species of Acacia have played an important role in Indian alchemy as well, where Acacia catechu has long been used as an additive to betel quids. Betel quids are consumed ritually by putting a small amount of the herbal blend in the mouth between the gum and cheek, similar to how chewing tobacco is consumed, allowing the active compounds to be absorbed by the mouth. Depending on the mixture, betel quids can act as either a stimulant or a sedative. In India, too, are two more species – Vachellia nilotica and Acacia farnesiana – from which are prepared traditional Ayurvedic medicines such as aphrodisiacs and muscle relaxants.[16]

Apropos the qualification of “the Compofition Grand Elixir,” we can only speculate that its composition was similar if not identical to that of Cagliostro’s elixir of Acacia. Although, Cagliostro was only one among a number of different Freemasons to be preoccupied with alchemical elixirs.[17] Indeed, in our next article, Alchemical Elixirs and Egyptian Freemasonry, we provide ample evidence that the use of elixirs and libations was somewhat central to the practices of the high grades of 18th century Masonic ritual.

Was Desaguliers employing a similar Acacia-based “Grand Elixir” privately in his own Masonic rituals? There is no evidence that this was the case, so we do not know. But, it is perhaps the only model which explains both the switch from Cassia to Acacia in the Master Mason degree during Desaguliers’ stint as Grand Master and Cagliostro’s use of an elixir of Acacia in an entheogenic context in his Egyptian Rite several decades later. None of this occured in a vacuum, and there is no doubting the psychedelic pursuits of the Royal Society from which both Ashmole and Desaguliers emerged.

We can think of no better way to close this article while at the same time providing pretext for the reader (and a sneak peek at what’s to come) than to end it with the pertinent quote from Cagliostro’s Egyptian Rite, which shows without a doubt that an elixir of Acacia has indeed been employed in an entheogenic, Alchemico-Masonic context in the past.

“The acacia is the primal matter and [when] the rough ashlar or mercurial part has been purified, it becomes cubical …It is thus that you may bring about the marriage of the Sun and Moon, and that you shall obtain…the perfect projection. Quantum suficit, et quantum appetite[18].”[19]

“The candidate…shall drink [the red liqueur placed upon the Master’s altar, thereby] raising his spirit in order to understand the following speech which the Worshipful Master shall address to him at the same time.

‘My child, you are receiving the primal matter… Learn that the Great God created before man this primal matter and that he then created man to possess it and be immortal. Man abused it and lost it, but it still exists in the hands of the Elect of God and from a single grain of this precious matter becomes a projection into infinity.

The acacia which has been given to you at the degree of Master of ordinary Masonry is nothing but that precious matter. And [Hiram’s] assassination is the loss of the liquid which you have just received…’”[20]

P.D Newman

Author of “Alchemically Stoned: The Psychedelic Secret of Freemasonry.”

Again, another enjoyable post! On behalf of all fans at Pansophers, thank you P.D Newman!

New readers, don’t forget to subscribe to our blog to stay updated. We’ll never send you any marketing emails. Just updates of our top latest blog posts!

WORKS CITED

Alleyne, Richard. “Robert Boyle’s Wish List.” The Telegraph, May 3, 2010.

Bennett, Chris. Liber 420: Cannabis, Magickal Herbs and the Occult. Trine Fay. Waterville, OR. 2018.

Churton, Tobias. Deconstructing Gurdjieff: Biography of a Spiritual Magician. Inner Traditions. Rochester, Vermont. 2017.

Desaguliers, John T. Cours de Physique Experimentale. Tome Premier. Paris, France. 1751.

Deveney, John P. Paschal Beverly Randolph. State University of New York Press. 1997.

Diesem, John L. “The Acacia, Its Origin and Meaning to Masonry.” Plumbline, summer 2004.

Faulks, Philippa. The Masonic Magician: The Life and Death of Count Cagliostro and His Egyptian Rite. Watkins. London. 2008.

Harrison, David. The Masonic Enlightenment: John Theophilus Desaguliers and the Birth of Modern Freemasonry. Knight Templar Magazine. http://www.knightstemplar.org/KnightTemplar/articles/enlightenment.htm. Accessed Nov. 4, 2018.

Jung, Carl G. Mysterium Coniunctionis. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ. 1989.

Levenda, Peter. The Tantric Alchemist: Thomas Vaughan and the Indian Tantric Tradition. Ibis Press. Lake Worth, FL. 2015.

Mackey, Albert G., Encyclopedia of Freemasonry and Its Kindred Sciences, New and Revised Ed. The Masonic History Co. New York and London. 1919.

Morris, S. Brent. “The Post Boy Sham Exposure of 1723.” Heredom, vol. 7, 1998, pp. 9-38.

Newman, P.D. Alchemically Stoned: The Psychedelic Secret of Freemasonry. The Laudable Pursuit Press. Norman, OK. 2017.

Ouspensky, P.D. In Search of the Miraculous: The Teachings of G.I. Gurdjieff. Harcourt, Inc. San Diego, New York, London. 2001.

Ratsch, Christian. The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications. Park Street Press. Rochester, VT. 2005.

Schatan, Deborah. “Mahjoun (Moroccan Hash Jam).” Munchies. http://www.google.com/amp/s/munchies.vice.com/amp/en_us/article/d7kgev/mahjoun-moroccan-hash-jam. Accessed Nov. 5, 2018.

Strassman, Rick. DMT: The Spirit Molecule: A Doctor’s Revolutionary Research into the Biology of Near-Death and Mystical Experiences. Park Street Press. Rochester, VT. 2001.

[1] Newman, p. 46

[2] While Cassia does contain both eugenol and coumarin, a stimulant and sedative, respectively, it is not possessed of any real entheogenic value.

[3] Harrison

[4] Fish

[5] Alleyne

[6] Bennett, p. 310

[7] Partridge

[8] Morris

[9] Faulks, p. 214

[10] Thomas Vaughan left his alchemical journals to Sir Robert Moray, the first president of the Royal Society and one of the first Speculative Freemasons. Therefore, it is likely that Desaguliers and perhaps even the author of the Post Boy exposure was familiar with Thomas and Rebecca Vaughan’s peculiar brand of Western Tantric alchemy.

[11] Levenda, p. 48

[12] Ibid. at p. 157

[13] Jung, p. 334

[14] Strassman, pp. 60-68

[15] Compare this notion of an internal and an external alchemy with the following description of the Fourth Way by its founder, Armenian mystic, G.I. Gurdjieff. Gurdjieff was initiated into a form of Sufism, a mystical sect of Islam, which had its own vibrant alchemical traditions. “The Fourth Way is sometimes called the way of the sly man. The ‘sly man’ knows some secret which the fakir, monk, and yogi do not know. […] Of the four, the fakir…by a whole month of intense torture…develops in himself a certain energy, a certain substance which produces certain changes in him. […] The monk…[through] a week of fasting, continual prayer, privations, and so on, enables him to attain what the fakir develops in himself by a month of self-torture. The yogi…knows that this substance can be produced in one day by a certain kind of mental exercises or concentrations of consciousness. […] In this way the yogi spends on the same thing only one day compared with a month spent by the fakir and a week spent by the monk. […] A man who follows the Fourth Way knows quite definitely what substances he needs for his aims and he knows that these substances…can be introduced into the organism from without if it is known how to do it. And so…he simply prepares and swallows a little pill which contains all the substances he wants and, in this way, without loss of time, he obtains the required results.” (Ouspensky, pp. 50-51) In this regard, the ways of the fakir, monk, and yogi may be likened unto neidan or internal alchemy, while the way of the “sly man,” on the other hand, may be likened unto waidan or external alchemy. As Tobias Churton points out in his book, Deconstructing Gurdjieff, the Armenian mystic was also a “closet Freemason.” (Churton)

[16] Ratsch, p. 29

[17] Vide the Masonic rites of Martinez de Pasqually, Pyotr Ivanovich Melissino, Hermann Fichtuld, Baron Hans Heinrich von Ecker und Eckhoffen, and Friedrich von Koppen.

[18] “Take as much as you need and as much as you have appetite for.”

[19] Ibid. at p. 214

[20] Ibid. at p. 225