In the 18th century, Karl Christian Friedrich Krause developed a philosophy he coined as panentheism. Although bearing the mark of influences taken from philosophers leading back to antiquity, Krause’s panentheism presents an important stage in the development of philosophy in the modern age, where his universal system brought together the classical Western traditions, Eastern philosophy obtained from influences such as the Upanishads, as well as the language of illuminism that was common in the post-Kantian era.

In terms of Rosicrucianism, Krause’s ideas were compatible with the universal ideologies of reform advanced in the Rosicrucian manifestos. Additionally, by following in the footsteps of figures such as Johann Amos Comenius, who’s own development of pansophy is crucial in the same regard, it should be clear how Krause’s panentheism becomes a torch bearer for the same type of pansophic idealism moving forward and beyond the 19th century. On a practical level, evidence shows how Krause’s philosophy was adhered to by groups like the 19th century Lichte Liebe Leben Lodge (a lodge whose namesake is referred to by the GD in their Cipher Manuscripts), as well as Heinrich Traenker’s Pansophia Lodge and Pansophic Society.

In the classical age, ideas surrounding mysticism and science were intrinsically entwined with philosophy, where metaphysics and theology often carried mutual influence and were often harmonized. The concept of science that we understand today would not have even carried the same connotation then. Meanwhile, the term mysticism sees substansive use in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when discourse moved towards a separation of science and religion. A major shift arrived in the era of scientific revolution where, in the 16th-18th centuries, inquiry into the natural world became increasingly empirical (i.e. leaning more towards the results of sensory perception or observable phenomena) and eventually leading to more rational methods of science taking favor (unfortunately, to some degree) over the past sciences attached to classical metaphysics and cosmology.

Although some were harboring mystical-scientific sympathies still at this time (like Copernicus, Galileo, Bacon, or Newton) by the time the Age of Enlightenment arrived in the 18th century, the Rationalist influences of Rousseau, Hume, Locke, and Kant gained acceptance as an advancement of philosophy and science putting an end to the “superstitious” and “dogmatic” tendencies of the classical and middle ages.

As the gaps between philosophy, science, and mysticism grew wider (or conflated in materialistic ways such as the case with some forms of deism) groups like the 18th century Gold Und- Rosenkreuzer, for example, began to appear as conservative and “anti-enlightenment” for holding a pietistic and revelation-orientated position towards mysticism, alchemy and magic. [1] On the opposing side of this debate, there was Weisphaupt’s Illuminatti—a group that pursued deism with a rejection of religious and faith-based texts, favoring instead an orientation towards acquired knowledge through rationalist science and philosophy. Similarly, groups like the Post Nubila Lux lodge and the De Dageraad in the Netherlands favored a rationalist form of pantheism, holding the more deistic view that God’s signature was present in the observable world through his laws and patterns existing in nature, yet without immanence. For many deists of the period, there was no interaction between God and the world, God had simply created the world and left it alone. Yet his signature was present in its structure, observable through scientific observation.

In contrast, the position Krause took with Panentheism avoided both the deistic position that sees God as separate and uninvolved with the world, as well as the pantheistic position that sees the observable and natural world as equivalent to God. Krause’s panentheism can be considered as a reconciliation of these two views, bridging together both the world of nature and reason, while at the same time resolving the problem of Cartesian dualism (mind vs. body) and Deistic dualism (God separate from cosmos).

Like the late Platonists such as Plotinus or Proclus, panentheism asserted a transcendent One, Monad (or God) that was unlimited by observable or intelligible reality. [2] In addition, since this transcendent divine was thought to holistically envelop and pervade all aspects of reality—including immanent deity recognized as the supernatural or divine working within the natural—panentheism might also appear reflective of ideas found in classic Hermetic texts such as the Corpus Hermeticum or Latin Asclepius. [3]

With foundations of philosophy reconciling nature, science and the divine, it becomes clear why panentheism presents a valuable system of mystic thought at a time when rational dualisms and cartesian distinctions gave rise to perceived separations between these figures. In some ways, Krause may be seen to be reiterating what emerged in the classical era, yet his contribution is valuable for presenting such ideas within the framework of the philosophical and conceptual discourse of his period.

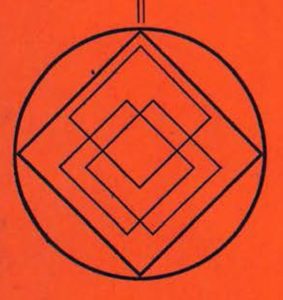

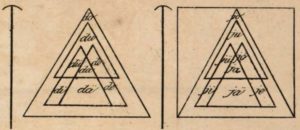

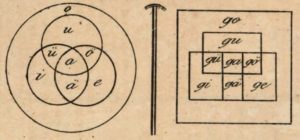

[The formula for Krause’s system is well explained through descriptions he produced through diagrams. For an explanation and diagrams of this system, please see the addendum at the end of this post]

Krause’s Background

In his formative years, Krause studied under the German Idealists in Jena: Friedrich W. Schelling, G. W. F. Hegel, and Johann Gottlieb Fichte. After receiving his doctorate in philosophy (1802), Krause began writing his own work. This, at first, fit squarely within the philosophical climate of the time that was decidedly post-Kantian; a period where inherent knowledge of the world was dependent upon mind and perception. For Krause, although he considered himself a legitimate successor to Kant, he had already begun to develop his own views of a “harmonious rationalism” that both resolved Kant but took another direction:

I can actually be regarded as Kant’s first successor, but I was so original, self-sufficient without intending it; that what appears as a continuation of Kant, was already the main thing I completed in 1803. This was before I was able to completely look at the relation of my own research and work to the Kantian, because I had then read and thought through Kant’s writings only very little. Rather, the main teachings of my system, completed in the years 1805 and 1806, were the key to the Kantian quest and made it possible for me to understand and appreciate the Kantian project from the highest standpoint…

…Kant considered the categories merely as finite concepts of the understanding, and they can only be considered as applicable to temporal sense perception. Therefore, he says explicitly that they are not rational concepts of ideas of reason, because, rather, an idea of reason is an infinitely extended category’ (Krause 1869: 228). [4]

Krause’s eccentricity made him distinct from his peers, but at times, this made him enemies. His devotion towards developing a concept of universal harmony brought him to the doorstep of Freemasonry when, after moving to Dresden to teach philosophy of law in 1805, he was initiated into the Lodge “Archimedes zu den drei Reißbretern” in Altenburg. Later that year, through a referral from the Archimedes Lodge, he became affiliated with the Loge zu den drei Schwerdtern und den wahren Freunden (Lodge to the three swordsmen and true friends), in Dresden. In the spring of 1808, he was elected as “redner” (lecturer) of that lodge. [5] So convinced was Krause of Freemasonry’s role in promoting social unity that he called the fraternal lodge a place where “a general association of all people will emerge, as humanity, blissfully linked, as church and state.” [6]

That next year, he wrote Höhere Vergeistung der echt überlieferten Grundsymbole der Freimaurerei (Higher Spiritualization of the True Traditional Fundamental Symbols of Masonry- 1809) and in the following year, Die drei ältesten Kunsturkunden der Freimaurerbrüderschaft (The Three Oldest Craft Records of the Masonic Fraternity – 1810). For his open discussion of secret Masonic symbols in these works, however, he was at first alienated, and eventually expelled from the lodges. [7]

Krause, however, continued his pursuit of establishing a universal brotherhood. In 1811, he published Das Urbild der Menschheit (The Ideal of Humanity). This work elucidates Krause’s idealism of universal harmony on a social scale, with humanity reflecting and working through the agency of God and nature:

Nature thus shows us the whole gradation of her internal spheres of life, and we are thus enabled to infer a similar gradation in her vital powers. Unregulated as the firmament may appear to us when presented by the waves of light, the mind yet feels the virtue of a higher sense of beauty and vitality wherein lies an inimitably beautiful rhythm and symmetry. This aspect of the firmament thus fills the breast with a pure and sublime sense, and reminds [hu]man[kind] that it should neither chain its spirit to itself nor the earth; and while this spectacle teaches us the impossibility of penetrating the depths of the heavens with intact vision, it at the same time encourages us to live out all our powers in this life as a worthy citizen of the terrestrial world. [8]

Reason and Nature, the two hemispheres of the universe, do not live isolated and separate from each other, but God, who created them both and bestowed upon them their inner free life, uniting them both socially into the highest, most complete, and universal harmony throughout the entirely of their being; and this eternally according to immutable laws…

…Yet we can still clearly behold the most intimate part of the interpenetration of Reason and Nature, for we ourselves belong to it, as all our spiritual and corporeal powers are consecrated to it. As, in fact, mind and body are the master-works and inmost sanctuaries of Reason and Nature, so Man is the living unity of the two and the inmost and most glorious part of that harmony of Reason and Nature which is established by God. [9]

Krause’s Influences

In his writings, Krause referred to many philosophers and schools of thought that he considered as his intellectual forebearers.

He was clear about how panentheism was a universal system of philosophy rather than just a system of science and metaphysics. In his Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, Krause presents a list of philosophers who approached their own version of a universal system; each of them as precursors. These included Bernard Telesio, Fracesco Patrizzi, Giordano Bruno and Thomas Campanella.

Telesio, in Krause’s view, introduced some of the earliest examples of the scientific method embracing sensory perception, while also developing theories of soul, temperature, and physics. For Krause, Telesio’s system was universal in the sense that it worked first through natural philosophy, rising from there to the human world, to the immortal soul, to divine virtue, and then further to God. [10]

Patrizzi, (a student of Telesio’s) developed his own system detailed in his Nova de Universis Philosophia, a text that is considered to be a proper introduction of Pansophy, in the late 16th century. In Patrizzi’s system, the cosmos begins as an emanation of light, with God as the first principle of all things. Everything is animated in his universe, with the whole world unified and connected through space and light. Four levels exist in Patrizzi’s cosmological system: Panaugia, or “All-Splendor”; Panarchia, or “All Principles”; Pampsychia, or “All-Soul” and Pancosmia, or “All-Cosmos”. [11]

Next, Bruno’s influence shines through ideas presented in his De monade, numero et figura liber (1591; “On the Monad, Number, and Figure”), which saw God in everything and everything within God’ with God effective in every point of the universe, as well as comprising the entire universe itself. For Bruno, God is the essence of beings, the substance of substances, the unity (entitas), through which things are (entia), the unity (monas) and the unity of the units (monadum monas). One might also consider how Bruno’s own form of panpsychism parallels that which is discussed in Krause’s panentheism. [12]

Campanella, like Telesio, sought a complete reformation of science, one that would also acknowledge the spiritual world. Practical philosophy, the philosophy of religion, and the philosophy of history were all considerations in Campanella’s system. He himself saw revelation and nature as the only sources of knowledge, with God openly bearing all through these two means of his creation, a creation itself that revealed the living book of the world. This book, if read correctly with an uninhibited, dispassionate spirit and with help from the external senses, was to reveal the entirety of nature. Campanella recognized nature as a living being, as well as being intrinsically connected to the spirit of man, revealing the basic truths of all science and unlocking all art. [13]

A review of Krause’s influences should also include John Amos Comenius. Like Comenius, Krause envisioned a human society based on free association that would encompass the whole world. Krause’s system of panentheism appeared to aspire to the same ideals approached by Comenius through: “a thorough abrasion of all science…a lamp of the human mind… a fixed norm of truth for all things … a reliable tablature for all business of life … [and] a blessed ladder to God …” [14]. It is without question that Krause was influenced by Comenius, as he comments on Comenius’ Panegersia (Universal Awakening) in the Tagblatt des Menschheitlebens (Daily Sheet of Human Life) in 1811.

Krause’s Outward Influence

During his lifetime, Krause’s public influence was not huge, although he did have many peers whom he exchanged ideas with. His rift with the Masons in Dresden probably didn’t help matters, and he thought that his failure to secure his former teachers’ position (Fichte) as Chair of Philosophy in Jena, was due to the turbulence he caused with the lodges. At the end of his life, Krause died penniless. It is known however that he influenced the likes of educator Friedrich Froebel (who invented the kindergarten system of education) by introducing him to Comenius’ works. He was also known to have exchanged some of his theories with Arthur Schopenhauer—the transcendental idealist philosopher cited by Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Freud, and Jung as important influences. The merits of Krause’s system however went largely unnoticed for generations.

One who did closely follow Krause’s ideology, however, was Johann Leutbecher, the founder of the Licht, Liebe Leben Lodge of Erlangen. Like Krause, Leutbecher was rather eccentric for his time, attempting several times to get his irregular LLL recognized by the Grand Lodge through petition and failing each time. [15]

A sense of Kruase’s influence on Leutbecher can be found in books he later wrote on Krause and Comenius: his Abriss der aesthetik oder der philosophie des schönen und der schönen kunst (Outline or philosophy of the aesthetics of beauty and fine art) [1837], and Lehrkunst (Art of Teaching) [1854].

Regarding Krause and Masonry, Leutbecher is quoted as saying the following:

…Masons will make unknown territory a known one. On the basis of the eternal revelation of the One God in nature and its laws, which are at the same time also the laws of the human being, as already recognized by our brother Krause, and always looking back on this book open to every spirit, he bases himself on the scientific-practical system of the free development of man, as indicated in the Masonian carpet, into the sphere of the ever-godlike existence on the irrefutable historical date of Ur-sabaeism. He shows ingenuously how man came to the eternal truths of a self-contained natural religion which were contained later in the Cults, Mysteries and the words of the philosophers. [16]

We can thus get a sense that Leutbecher’s concept of Freemasonry was also one of a universal fraternity, like Krause; open and embracing to all.

Another who supported the writings of Krause was Heinrich Traenker. In the publication put out by his Universal Pansophic Society in North America, the Pansophic Intellectualizer, Traenker published Krause’s Ideal for Humanity in volumes from July 1936 to March 1940. In the same publication, Traenker writes the following:

An expounder of pansophy, too, was the freemason K. Chr. Fr. Krause, who always considered himself a follower of Comenius. Krause completed the pansophy of Comenius in the philosophic aspects. He also tried to reform freemasonry in a pansophic sense. Herein he met great resistance, [but] in its stead he founded on March 21, 1808, the “Universal Union of Humanity [17]

Additionally, in Traenker’s Constitution of the Societas Pansophica Universalis of 1932, he published this, connecting Krause to the original Rosicrucian movement:

All-wisdom is the universal law; alone through will and love to be fashioned by all thinking beings into the wise deed. Wise deeds guarantee an ultimate progress of the individual as well as of humanity, so that the eternal good and the greatest happiness reach gradually all of humanity in order that it can work in the spirit and will of the great:

General Reformation of the Fraternity of the Rose Cross

From the year 1614 and the therewith ideally connected

&

Universal Brotherhood

Founded by Brother K. Chr. Fr. Krause on the 21st of March, 1808,

and also to complete in an ideal-real manner the highest pansophic idea

The ambition of Traenker’s Pansophic Society was an ideal of universal reformation and brotherhood—ideas that are similarly expressed in both the Rosicrucian manifestos and Krause’s Ideal for Humanity. What Traenker was referring to regarded the date of 1808 remains unknown. During that spring, however, Krause was elected as his lodge’s lecturer. And, it is also pointed out elsewhere, that after his expulsion from the lodge, he sought to organize a foundational reform of the Grand Lodge. This event might appear as the motivation for the creation of Krause’s new “Universal Brotherhood”. [18]

But perhaps the most revealing clue of Traenker’s ambitions to align his Pansophic Society with Krause’s Universal Brotherhood is seen on the cover of the Pansophic Intellectualizer. As we shall see in the following addendum, the image is modeled off of Krause’s diagrams.

Krause’s Philosophy

(The items of this section largely derive from Göcke [see bibliography], with additional research into Krause’s work)

For Krause, the absolute is called the Orwesen, indicating a complete “unity of being”. This is based on the root of the word Or meaning “joined” and wesen meaning “being”. The next ontological level down, denoting the first distinction or state of difference from the absolute, is called the Urwesen, indicating a “unity-as-origin”. For this, the root Ur figures as the “primordial”, and when combined again with the term wesen, indicates a point of origin, or first matter, from the condition of the absolute. The result of these two conditions reveals a “God of the philosophers” (the Orwesen) on one hand, and the “God of religion” (the Urwesen) on the other; with neither equated with the entirety of the universe per se.

Krause’s view in Panentheism held that the world exists as part of God in as much as God is Orwesen (the absolute). However, it is also distinguished from God in as much as God is Urewesen (God as the grounding or foundation of the world.) The concept sees a similarity in late Platonic philosophy where the demiurge appears as the first difference from the “One” (as the Nous/Mind of the One) involving the principle of logos (meaning “reason”, “order”, “measure” or “plan”) who organizes the cosmos.

What Orwesen and Urwesen further relate to are the Brahman and Atman of Hindu philosophy, giving a fuller view of Krause’s model. Whereas Brahman is the universal principle (indicating the ultimate reality) Atman is considered the self or soul of that principle. Those following Kabbalah might find similarity with the Ain Soph (the principle of limitlessness, beneath the “Ain” which is “no-thing”) and the Ain Soph Aur (the limitless or eternal light which extends out of the Ain Soph).

Krause’s visual diagrams then can be applied equivocally to each level (or aspect) of reality to illustrate his philosophy. The model is essentially based on the principle of unity (the Orwesen) being comprised of opposing essentialities of selfhood and wholeness that themselves contain parts that are both distinct and unified (the Urwesen). For Krause, all unities (including both the absolute unity as well as the differing unities which are constituents of it) are based on smaller unities of unity and difference.

Krause’s model applies to most circumstances where a need to understand essentialities in terms of the relationship between their constituents and wholeness is involved. In Krause’s philosophy, he used these diagrams not only to address the idea of God or the universe but also the individual subjects of science, the world, the ego, the body, the mind, nature, reason, and humanity. The same model, in other words, applies to each aspect of reality being looked at.

Using the circular diagram above, the following for example can be stated in relation to Orwesen and Urwesen:

If we conceive of Orwesen as o, then the analysis of Orwesen, in itself, begins with the recognition that there is an opposition of essentialities i and e. Because Orwesen cannot be in any opposition, [by its own definition as the absolute] the opposition between i and e is an opposition [with]in the essence of Orwesen itself. Since, however, because of the unity of the divine being, the relata of the opposition have to be united themselves, [indicated by] ä, and have to be united in so far as they constitute the intrinsic nature of Orwesen, there has to a principle of unity, u, that Krause calls Urwesen, in virtue of which this is possible and actual. Urwesen, u, is both separated from i, ä, and e, as well as united with each of them, ü, a, ö. Now because selfhood and wholeness are reason and nature, because humanity is the union of reason and nature, and because the world is the union of nature, reason, and humanity, we can, in a first step, let i refer to reason, e to nature, and ä to humanity and then will be able to see that the world is an intrinsic determination of Orwesen. When, in a second step, we consider Urwesen, u, to be the principle in virtue of which the world exists, we immediately see that as the principle of the world, Urwesen is both separated from and united with the world: u, ü, a, ö. All of this, even the distinction between Urwesen and the world is an intrinsic and essential determination of the one divine being, Orwesen. [19]

Furthermore, the following could be stated for the ego, mind, and body, since for for Krause, the grounds for the unification of nature and reason only become fully understandable once the ego can accomplish the fundamental intuition of God. Additionally, since the goal of humanity was to achieve this fundamental intuition where the ego directly intuits the nature and existence of the highest principle of science—nature, reason, and humanity are thereby fully interconnected:

When o denotes the ego as such, i denotes the ego-as-mind and e denotes the ego as body, then the fundamental intuition of the ego, in itself, will enable you to see that in the ego there is a union of mind and body, that entails a union of reason and nature, ä. That the ego is not reducible to either i, ä, or e, and is not in external opposition to mind, body, and their union, just means that the ego, in itself, is also the higher unity of these essentialities, u. In virtue of its being the higher unity, however, it is at the same time united with i, ä, and e, visualized as ü, a, and ö. [20]

Concerning science, in Krause’s Das Eigentümliche der Wesenlehre (1890), on page 137 he states “The one science is the structure of all the individual sciences, all of which are in it, just as the structure of every individual essence is in Essence. Or, rather, all is in itself and for itself in the one science as the structure of both finite and individual beings.” Here, this is explained in accordance with the diagram:

First: when o represents the organic system of science as such, i, e, and u represent the principal sciences of selfhood, wholeness, and the principle of their unity, Urwesen, where Krause addresses the union of selfhood and wholeness, humanity, as the fourth principal science, ä. This immediately entails the existence of further special sciences that investigate particular features of the relation between selfhood, wholeness, humanity, and Urwesen: ü, a, and ö. That is, for instance, ä is the science of the relation between selfhood as part of the world and the principle in virtue of which selfhood exists in the world. second: If i, e, and u represent any three categories, we obtain, according to Krause, immediately further categories by looking at the unities and differences of these categories as represented in the diagram, where i, e, and u can also represent the same category or only two different categories. [21]

Conclusion

Ultimately, Krause’s panentheism approached a reconciliation between metaphysics, reason, intuition, rational thought, and science. Yet, it also provides a robust model of mystic philosophy with several possibilities that can applied to aspects of matter, God, religion, science, as well as the cosmos.

The implications suggested by his system appear as boundless as they are revealing. To deduce, for example, that the physical world is a part of the divine and that the divine is present in all aspects of the world (as others have pondered before—but yet, additionally, to suggest that reason, nature and humanity are all aspects of that world) means to accept that the divine is present in all aspects of reason, nature, and humanity—yet, as well, that each participates with the nature of the divine itself. To then suggest also that ego is not comprised solely of “self-identity” (as might be considered for example in the Freudian sense) but instead, that ego is the union of ego-as-mind and ego-as-body, then the physical world being conjoined in reality with the “mind of the world” may be brought forth.

For philosophers and mystics alike, Krause’s panentheism is a valuable resource. Rarely does a figure come along who appears as driven intellectually as they seem genuinely touched both intuitively or spiritually. Even this though is explained through a description of Krause’s panentheism:

It is found in the intuition of Essence, that Essence as the one—as itself or in itself, under itself, and through itself—is everything, [and yet] also the epitome of everything finite. Therefore, this insight is resolved through recognizing that the One is—in itself and through itself—also everything. And, because it is known through the intuition of Essence that God is also everything—in and through Himself—that the organic system of science can indeed be called panentheism. [22]

…a four-fold whole… nature, reason, humanity, and above these, God. It can therefore be said that the whole of science proclaims itself through spirit as knowledge of God. And, as a natural science, as a rational science, as a human science […], and as a science of God, provides that God is recognized as being above the world. [23]

Bibliography

Göcke, Benedikt Paul (2018). The Panentheism of Karl Christian Friedrich Krause (1781-1832): From Transcendental Philosophy to Metaphysics. Peter Lang Gmbh, Internationaler Verlag Der Wissenschaften.

Krause, Karl Christian Friedrich (1887). Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie: Aus Dem Handschriftlichen Nachlasse Des Verfassers (History of Philosophy, From the Author’s Handwritings). Otto Schultz, Liepzig.

Krause, Karl Christian Friedrich (1821). Die drei ältesten Kunsturkunden der Freimaurerbrüderschaft. (The Three Oldest Arts of the Masonic Brotherhood) Arnoldischen Buchhandlung, Dresden.

Krause, Karl Christian Friedrich (1828). Vorlesungen über das System der Philosophie. (Lectures on the System of Philosophy) Göttingen: Dieterich, Printed by CPI books GmbH, Leck.

Krause, Karl C. F. 1890. Das Eigentümliche der Wesenlehre, nebst Nachrichten zur Geschichte der Aufnahme derselben (The Peculiarity of the Doctrine of Beings and the History of their Inclusion). Leipzig: Otto Schulze.

Krause, Karl C. F. (1869). Der zur Gewissheit der Gotteserkenntnis als des höchsten Wissenschaftsprinzips emporleitende Theil der Philosophie. Vorlesungen über das System der Philosophie (Philosophy Leading to Certainty of the Knowledge of God as the Highest Scientific Principle. Lectures on the System). Prague: Tempsky.

Krause, Karl Christian Friedrich (1900). The Ideal of Humanity and Universal Federation. T. & T. Clark, Edinburgh.

Copenhaver, Brian P. (1995). Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge University Press

[1] See, McIntosh, Christopher (2012). The Rose Cross and the Age of Reason: Eighteenth-century Rosicrucianism in Central Europe and Its Relationship to the Enlightenment. State Univ of New York Press (pp 13-14)

[2] Krause referred to the absolute as “Orwesen”. See the addendum for an explanation.

[3] Copenhaver, (C.H. V.2; 1992:18) “The one who alone is unbegotten is also unimagined and invisible, but in presenting images of all things he is seen through all of them and in all of them….the lord, who is ungrudging, is seen through the entire cosmos….there is nothing in all the cosmos that he is not. He is himself the things that are and those that are not. Those that are he has made visible; those that are not he holds within him.”

[4] Göcke, p 13.

[5] About Karl Christian Friedrich Krause The Freemason. (n.d.). Freemasonry Research Forum and Virtual Library of Rare Masonic Books. https://www.freemasonryresearchforumqsa.com/krause/about-karl-christian-friedrich-krause.php

[6] Krause, Karl C. F. 1903. Der Briefwechsel Karl Christian Friedrich Krauses: Zur Würdigung seines Lebens und Wirkens. Leipzig: Otto Schulze. P 192

[7] Higher Spiritualization of the True Traditional Fundamental Symbols of Freemasonry – Höhere Vergeistigung Der Echt überlieferten Grundsymbole Der Freimaurerei.- By Karl Christian Friedrich Krause. (n.d.). Freemasonry Research Forum and Virtual Library of Rare Masonic Books. https://www.freemasonryresearchforumqsa.com/krause/

[8] Krause, The Ideal of Humanity and Universal Federation, p25.

[9] Ibid, pp 30-31

[10] Krause, Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie, pp. 239-240

[11] Ibid, p 240

[12] Ibid, pp 240-244

[13] Ibid, p 244-247

[14] Krause, Die drei ältesten Kunsturkunden der Freimaurerbrüderschaft, p. 30

[15] See: “Die Bauhütte: Organ für die Gesamt-Interessen der Freimaurerei” Volume 31, 1888. page 5, the “Journal of proceedings of the M. W. Grand Lodge of the Ancient and Honorable Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons, of the State of New Hampshire” (1869), and the “Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the State of New York” (1865).

[16] Polak, Mozes Salamon (1855). Die tapis in ihrer historisch-paedagogischen, wissenschaftlichen und moralischen Bedeutung. Amsterdam, Günst. Forward by Johann Leutbecher.

[17] Traenker, Heinrich “History of the Rose Cross Movement” Pansophic Intellectualizer, Feb. 1936, Vol I No. II, p 25

[18] Göcke, p 22

[19] Göcke, pp 127-128

[20] Göcke, p 80

[21] Göcke, p 138

[22] Krause, Karl C. F. (1869). Der zur Gewissheit der Gotteserkenntnis p. 313

[23] Krause, Karl C. F. (1869). Der zur Gewissheit der Gotteserkenntnis p. 25