Pansophers has been a long time fan of Dr. Hereward Tilton which is why we are proud to present the first of his articles published on this blog with us. Hereward has taught on European esoteric traditions at the University of Exeter, the University of Amsterdam and the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich. Our fans will best know him for his published work on Rosicrucianism, magic and alchemy titled “The Quest for the Phoenix: Spiritual Alchemy and Rosicrucianism in the Work of Count Michael Maier (1569-1622).” We are excited to see more from Hereward as he currently rolls out his findings from reading the source materials of the Gold und Rosenkreuzer, a favourite topic of everyone here!

I came to Austria on the trail of the ʾûrîm and tūmmîm (אוּרִים וְתֻמִּים, ‘lights and perfections’). Enigmatic objects born upon the ḥōšęn (חֹשֶׁן, breastplate) of the high priests of pre-exilic Israel, they were lost to history until their resurrection as ritual magical artefacts by the alchemico-Cabalist Heinrich Khunrath in the late sixteenth century. A century later we find them among the initiates of the Gold- und Rosenkreuz; in accordance with Khunrath’s tradition, they are conceived as Philosophers’ Stones, inlaid upon an object composed of the seven metals and utilised for scrying by the seven Magi at the order’s peak. Having studied Gold- und Rosenkreuz manuscripts in London and Munich detailing the construction and use of this artefact, I was invited by Thomas Hakl to inspect the Octagon copy of the Thesaurus thesaurorum (Treasure of Treasures), an extensive manuscript compendium of the order which contains fleeting references to the Urim and the Thummim (referred to synecdochically as a singular ‘Urim’), as well as to the electrum magicum upon which they were inlaid. With a wealth of manuscript and printed Rosicrucian material to hand, and ensconced within what seemed to be the very vault of Christian Rosenkreuz, I set about a source-critical analysis of the Thesaurus thesaurorum which would cast a great deal of light not only upon the cultus (group religious ceremonial) of the Gold- und Rosenkreuz, but also upon the history of this important occult order. Perhaps most surprisingly, I discovered that a pre-Rosicrucian Christian Cabalistic tradition handed down by a Böhmian exile in Amsterdam lay at the heart of the order’s doctrine and praxis. Indeed, while the quest to uncover the origins of the Gold- und Rosenkreuz has shifted to Italy in recent decades, my own research suggests those origins lie well north of the Alps.

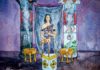

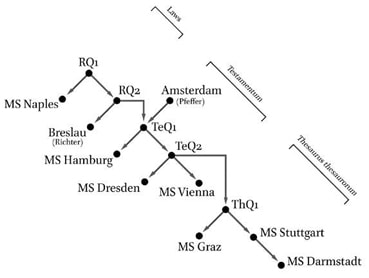

Only a brief précis of my findings is possible here. As a collection of seemingly disparate magical and alchemical procedures utilized by the order, the Thesaurus thesaurorum resembles a grimoire. The full title of the Octagon manuscript is Thesaurus Thesaurorum a Fraternitate Rosae et aureae Crucis Testamento consignatus, et in Arcam Foederis repositus suae Scholae Alumnis, et Electis Fratribus. anno. MDLXXX (The Treasure of Treasures, set down as a testament by the Fraternity of the Rosy and Golden Cross, and kept in the Ark of the Covenant for the protégés and chosen brethren of their school). Similar eighteenth-century compendia entitled Thesaurus thesaurorum exist in Darmstadt and Stuttgart.[1] However, while their titles vary only slightly, their content diverges from the Octagon manuscript in certain significant ways. For heuristic purposes I will refer to the Thesaurus thesaurorum in the singular as a distinct recension or family of documents; nevertheless, these compendia emerge from an extensive matrix of interrelated texts, their titles and content evolving in accordance with the practical and doctrinal proclivities of numerous redactors. As such they constitute not only a record of the order’s practice, but also a veiled record of its history, which can be uncovered via an examination of variations in textual content, terminology, iconography, orthography and chirography.

Figure 1. The three manuscripts of the Thesaurus thesaurorum: Octagon (A), Darmstadt (B) and Stuttgart (C).

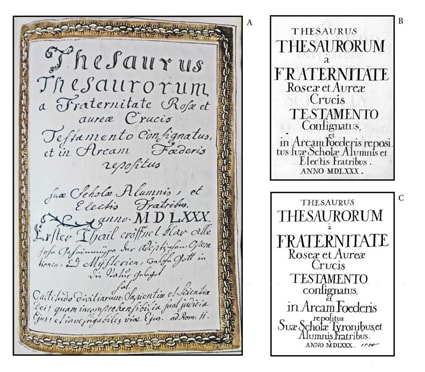

Figure 2. The three manuscripts of the Testamentum: Hamburg (A), Dresden (B) and Vienna (C).

Thus the Thesaurus thesaurorum is derived from a family of earlier, shorter alchemico-magical compendia associated with the Gold- und Rosenkreuz: the Testamentum, which also exists in three eighteenth-century versions at Vienna, Dresden and Hamburg.[2] Of these three versions, the manuscript most closely related to the textual genealogy I am tracing here – the Hamburg codex – is entitled Testamentum societatis aureae & roseae crucis darinnen gewiße geheime Operationes alß große Mysteria unseren Kindern u. Schülern Magiae divinae & Cabalae eröffnet werden. I. W. R. (Testament of the Society of the Golden and Rosy Cross, in which certain secret procedures are revealed as great mysteries to our children and students of divine magic and Cabala. I. W. R.). All three versions of the Testamentum share the same basic structure and content:

a) a pseudo-history tracing the origins of the order and its prisca magia to the Hebrew patriarchs, who utilised the Urim to evaluate new candidates for their ‘magical priesthood’

b) the laws of the order and details of the neophyte initiation ceremony

c) nine chapters of ‘ecstasies’ or secret procedures concerning the production of essential tinctures from the mineral realm (bismuth, antimony, silver ore, sulphuric acid, mercury, rock salt), vegetable realm (wine), animal realm (blood, urine, excrement) and astral realm (dew, rainwater, snow, air, earth); the same material is divided into only seven chapters in the Vienna and Dresden codices

d) nine chapters devoted to magical doctrine and practice (the creation of a homunculus from rotting human flesh; rejuvenation via fasting with animal and astral tinctures; rainmaking with a magical electrum sphere; the fertilisation of plants with an astral tincture; the construction of a type of camera obscura with magical electrum mirrors; and the production of a sympathetic powder that kills at a distance); the same procedures (bar the last) are presented in only seven chapters in MS Vienna and MS Dresden

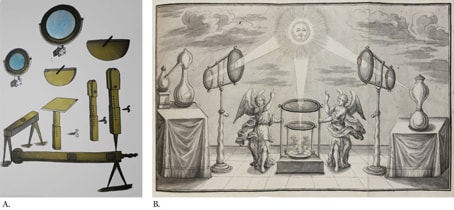

Figure 3. Construction and operation of a ‘magical machine’ for producing the secret fire of nature: Thesaurus thesaurorum, Octagon Collection (A) and Arcana divina, Beinecke Library MS 88 (B).

Sections a), b) and c) of the Testamentum correspond closely to book one of the Stuttgart and Darmstadt versions of the Thesaurus thesaurorum. However, section c) is missing from the Octagon Thesaurus thesaurorum: in its place we find a different text which corresponds in certain places to another family of manuscripts, the Arcana divina.[3] While this variant text also deals with the production of tinctures from the four realms, its defining feature is the employment of a ‘secret fire of nature’ produced by a solar lens (figure 3).[4]

Section d) of the Testamentum corresponds to book two of all three versions of the Thesaurus thesaurorum, which is entitled De magia divina et naturali. However, in place of the passage on the homunculus, the Thesaurus thesaurorum describes the attainment of planetary angelic visions with a lapis magicus created through repeated ingestion of gold with one’s own urine. As the Testamentum evolved into the Thesaurus thesaurorum it also accrued additional alchemical recipes: these comprise the third and fourth books of the Stuttgart and Darmstadt manuscripts. Both of these manuscripts are written by the same scribe and – judging by their chirography – both date to circa 1760-1780. The pseudonymous author of the Erklärung des mineralischen Reichs (1783) – ‘Joseph Ferdinand Herverdi, M. D. in Rotterdam’ – was probably a late redactor of text in both the Stuttgart and Darmstadt manuscripts,[5] which nevertheless have southern German Catholic origins. Thus the most recognisably Böhmian material in the Testamentum – chapter ten (Von der geheimen Magia) and chapter eleven (Von der geheimen Cabala) – is replaced in the Stuttgart and Darmstadt versions of the Thesaurus thesaurorum by a much shorter exposition drawn from the popular definition of ‘Cabala’ given in Toxites’ Onomastica, as well as from a condemnation of the ‘degenerate’ and ‘damned’ Jewish Kabbalah given in a Jesuit (!) Bible commentary.[6] The exposition in the Stuttgart Thesaurus is still in the original Latin; in the German translation given in the Darmstadt Thesaurus its explicitly Catholic reference to the ‘Apostolic See’ is excised.[7] The Octagon manuscript derives from a common source (ThQ1; see figure 4) which had the same Latin exposition of the Cabala, as it lends that Latin a different meaning in at least one place;[8] although it usually abridges the common source,[9] the Octagon manuscript also preserves certain sections which have been excised from the Stuttgart and Darmstadt manuscripts. Its chirography suggests a date of circa 1780-1800; idiosyncrasies in its title and laws indicate it is related to – or identical with – a copy of the Thesaurus thesaurorum once held by the Supreme Council of the Ancient and Accepted Rite of Freemasonry in London.[10]

Figure 4. Source history of the Gold- und Rosenkreuz laws, Testamentum and Thesaurus thesaurorum (illustrating the minimum possible number of redactions; more complex permutations are possible).

The title of the Thesaurus thesaurorum states that its raison d’être is the transmission of esoteric knowledge within the order; the fact the text is committed to safe-keeping within the Ark of the Covenant is symbolic of its status as restricted knowledge controlled by the ‘high priests and consummate Magi’ alone. Given the order reconstructed the artefacts of the ancient Hebrew cultus for its ritual practice, the ‘Ark’ may also have been a physical object: thus in the related initiatory rituals of the Asiatic Brethren the Urim is taken from the Holy of Holies amidst the burning of entheogenic incense.[11] A Freemasonesque concern with the Tabernacle and its fixtures is evident throughout the order’s Hebrew patriarchal pseudo-history given in both the Thesaurus thesaurorum and the Testamentum, which identifies Bezalel – the chief artisan of the Ark and its sanctuary – as the first Imperator. The order’s alchemical and magical practices are portrayed as traditions established by the patriarchs: thus the twelve stones of the Urim are associated with the twelve stones collected by representatives of the twelve tribes at the parting of the Jordan (Joshua 3.1-4.24). Together with the twelve ‘magical priests’ carrying the Ark, these men represent the order’s traditional membership quota (twenty-four).[12]

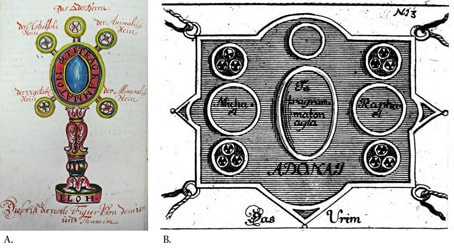

Despite their restricted status,[13] neither the Thesaurus thesaurorum nor the Testamentum is a complete record of the order’s doctrines and practices. Although the Urim and related magical artefacts are alluded to, their manufacture is not explained: indeed, while the Testamentum refers to the pertinent order tract (Magia divina),[14] the scribes of the Thesaurus thesaurorum – whether intentionally or otherwise – give the impression they are not privy to this secret.[15] A higher-grade treatise explains why this knowledge is restricted: only those whose hearts are ruled by the Holy Spirit may construct the Urim.[16] More complete texts describing the production of essential tinctures or ‘stones’ from the four realms and their employment in the creation of the Urim include R. Abrahami Eleazaris uraltes chymisches Werck (depicting a pendant breastplate with twelve stones),[17] the Schrifftliche Unterrichtung der wahren Weißheit von der F. R. C. (depicting group use of a free-standing artefact with six stones),[18] the Himmlisches und übernatürliches Geheimnis des Geistes und der Seele der Welt (depicting individual use of the free-standing artefact),[19] and γνῶθι σεαυτόν seu noscete ipsum: Sextus sapientiae liber verus ac genuinus (depicting both individual and group use of the free-standing artefact).[20] While the number of stones in the pendant Urim corresponds to the pseudo-history of the Thesaurus thesaurorum and the Testamentum, a free-standing Urim appears in their description of the neophyte initiation ritual, indicating that an early redactor was aware of both artefactual traditions.

Both the pendant and the free-standing Urim are created by inserting stones from the four realms into crystal fixtures within artefacts of electrum magicum – an alloy of the seven metals first described in the pseudo-Paracelsian Archidoxis magica, which details the creation of magical mirrors and spirit-summoning bells similar to those described in the order’s manuscripts.[21] At the centre of both types of Urim the Tetragrammaton is inscribed and a larger stone incorporating all four types of stone is inserted; the free-standing artefact is crowned by a further colloidal gold ‘ruby’ manufactured with a liquid ‘fire of the Lord’.[22]

Figure 5. The Urim in its free-standing and pendant forms: Schrifftliche Unterrichtung der wahren Weißheit von der F. R. C., Wellcome Library MS 4808 (A) and R. Abrahami Eleazaris uraltes chymisches Werck (B).

The significance of this sacred object to the order cannot be overemphasised: it is ‘Jehova Jesus himself’, and the divine light shining within it is the Holy Spirit.[23] When in use at the Imperator’s dwelling the Urim is placed upon a table between two ever-burning lamps fuelled by the ‘fire of the lord’;[24] as they scry, the seven Magi at the order’s apex sit in chairs inscribed with the characters of the seven planets (a fact indicative of a further initiatory hierarchy within the grade of Magus corresponding to the angelic order), while the rest of the gathered brethren must remain lying with their faces to the floor in a state of ‘inner communion’ with God.[25] Within the artefact’s stones various scenes are revealed, including cosmogonic processes reminiscent of Böhme and apocalyptic visions of the future.[26] The Urim also grants the Magi powers of surveillance and control: through scrying the activities of lower brethren may be observed, while their hearts are probed and God’s judgment on their fate is learnt as the central stone brightens or darkens.[27] This vetting function explains the presence of the Urim at the initiation ceremony described in the Thesaurus thesaurorum and the Testamentum.[28] Thus the order’s most prominent member during its quasi-Masonic phase, crown prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia, became a Magus himself after he ‘passed the Urim and Thummim and was approved’ in April of 1783.[29]

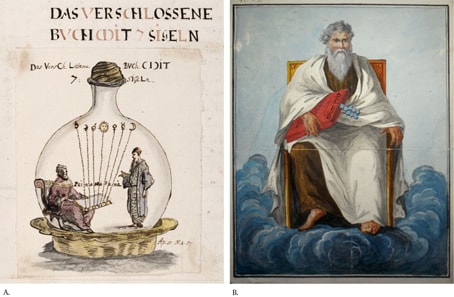

What are the origins of this extraordinary Christian practice? Heinrich Khunrath (1560-1605) details the production of magical artefacts from electrum magicum in his restricted esoteric teachings;[30] he also refers to the Urim and Thummim in his printed work as artefacts manufactured from the Philosophers’ Stone by which God reveals his secrets to the theosopher;[31] what is more, a remarkable manuscript tableau uncovered by Forshaw depicts Khunrath consulting just such artefacts in order to secure the aid, solace and counsel of ‘a great benevolent spirit from the Empyrean’.[32] Before an altar the ‘practising theosopher’ beseeches God to grant him success; upon the altar-cloth the preconditions of that success – prayer, fasting, penitence, faith, humility, alms-giving – are written, together with a reminder that the pure in heart are blessed, ‘for they shall see God’ (Matt. 5.8). Upon the altar a Psalter (marked ‘the theosopher’s obedience-book’)[33] lies next to a spirit-summoning bell of electrum magicum.[34] Two polished mirror-like stones marked ‘Urim’ flank a further ‘wonder-working stone of the wise’ – the ‘Thummim’ – in which the emblems of an opened copy of Khunrath’s Amphitheatrum sapientiae aeternae are reflected.

Figure 6. Consulting the Urim and Thummim. Tabulae theosophiae Cabbalisticae, British Library, Sloane MS 181.

As it is infused with a ‘powerful ray of divine omnipotence’, the tableau in question is both a magical artefact and an instructional aid[35] in an esoteric tradition transmitted by Khunrath to his followers. The tableau itself appears to date from the early seventeenth century:[36] but how did this tradition – somewhat modified but still fully recognisable – come to play such a central role in the Gold- und Rosenkreuz in the following century? Let us proceed to a closer analysis of the Thesaurus thesaurorum.

Stylistic and redactional evidence indicates the earliest identifiable redactor of the Testamentum (and hence the Thesaurus thesaurorum) was Ulrich Pfeffer (?-1680), a surgeon and physician from Itzehoe in Holstein. Indeed, it appears Pfeffer was the custodian of an esoteric tradition that forms an essential foundation for the entire edifice of the doctrine and practice of the Gold- und Rosenkreuz. Of Pfeffer’s early life I know nothing, except that he mistook the ‘serpent’s guile’ of his academic training for wisdom, and subsequently spat that bitter poison out.[37] In 1660 he relinquished Lutheranism and became a member of the Society of Friends (‘Quakers’);[38] this conversion was probably contingent upon the arrival in Friedrichstadt in 1657 of the Quaker missionary William Ames.[39] According to Friedrich Breckling – a Radical Pietist close to the Holstein Quaker circle[40] – Pfeffer subsequently turned away from the Society of Friends and devoted himself to the study of Böhme, van Helmont, Weigel, Paracelsus and Basil Valentine.[41] Whether his inclinations at the time were primarily Quakerish or Böhmian, Pfeffer moved to the Netherlands, a relatively safe haven for inspirationists of all stripes. There he lived on the Egelantiersgracht in Amsterdam.[42] Along this short canal lay the house and offices of Christoffel Cunrad, the Dutch publisher of Böhme, von Franckenberg, Penn and Breckling; between 1672 and 1680 Breckling himself lived and worked there with Cunrad’s family.[43] From 1673 Egelantiersgracht was also the site of Johann Georg Gichtel’s communal house of Böhmians – the Engelsbrüder (Angelic Brethren), so named for their commitment to angelification in this life.[44] While it is not clear if Pfeffer resided at either of these houses,[45] it is evident he was extremely close – both geographically and ideologically – to this circle of Böhmian exiles. Thus Pfeffer’s praise of Böhme is included in the foreword to the edition of Böhme’s Theosophische Schriften published in Amsterdam by Heinrich Betke in 1675.[46] Breckling records Pfeffer’s death in 1680, a year in which he says many thousands died of the plague in Amsterdam.[47]

Pfeffer left behind a large corpus of unpublished and in part fragmentary manuscript texts. These contained teachings of an esoteric nature intended for Pfeffer’s ‘disciples’ that would normally – more Cabalistico – be passed on orally.[48] A partial inventory of these texts was published in Franz Rottman’s Treuhertzige Vermahnung (1680), and a more complete list appeared three years later in Georg Ernst Aurelius Reger’s Gründlicher Bericht auff einige Fragen (1683); [49] both of these books from Rottman and Reger appear to have been stitched together from Pfeffer’s work, [50] while a further anonymous work published by Reger in 1686 is also likely to be Pfeffer’s.[51]

Reger’s inventory of Pfeffer’s manuscript works includes the titles of three texts associated with the Gold- und Rosenkreuz. Firstly, there is the Cabala et philosophia naturae et artis; the subtitled description states it was written ‘for the instruction of my favourite disciples out of love’.[52] Two eighteenth-century manuscripts with this title exist at The Hague and Amsterdam, and both are ascribed to Friedrich Gualdi of the Italian Cavallieri dell’ Aurea Croce (cf. infra).[53] The Amsterdam copy is bound together with the aforementioned Himmlisches und übernatürliches Geheimnis des Geistes und der Seele der Welt – a work ascribed to Trithemius, but which nevertheless contains Pfeffer’s words verbatim in a chapter entitled ‘Was Magia naturalis’.[54]

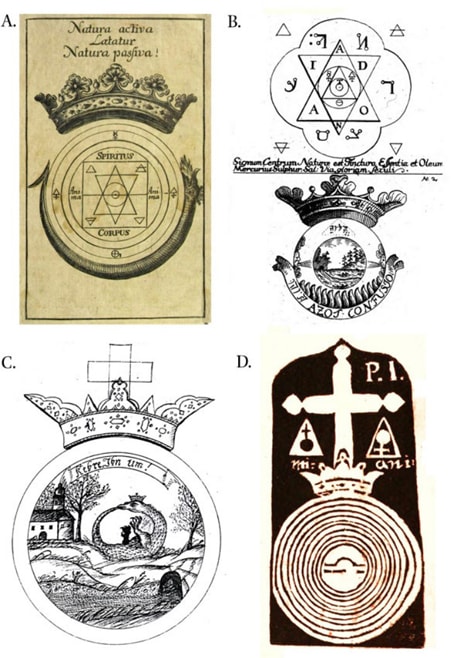

Secondly, Reger lists among Pfeffer’s works an Occulta philosophia, coelum sapientum et vexatio stultorum, which shares its title with the Occulta philosophia, coelum sapientum et vexatio stultorum published in 1737 by Augustinus Crusius of Erfurt. In the faux-Jewish Uraltes chymisches Werck (1735) of ‘Abraham Eleazar’, the same publisher announces a list of manuscripts he is ‘inclined’ to print, which includes the Occulta philosophia, a work of ‘Eric Pfeffer’ entitled Secretum denutatum[sic] philosophiae occultae and the Coelum reseratum chymicum of pseudo-Thölde.[55] While the Secretum denutatum philosophiae occultae was not printed, the other three works – Occulta philosophia, Uraltes chymisches Werck and Coelum reseratum chymicum – contain large swathes of text that are also to be found in the Testamentum and the Thesaurus thesaurorum, as well as a closely related iconography .[56]

Figure 7. Iconography of the Coelum reseratum chymicum (A), Uraltes chymisches Werck (B), Testamentum (MS Hamburg) (C) and the Occulta philosophia (D).

A third text associated with the Gold- und Rosenkreuz that is listed in Reger’s inventory of Pfeffer’s works is the Testamentum an die Kinder der Kunst und Weißheit Göttlicher Magiae, Englischer Cabalae und Natürlicher Philosophiae. There is no further indication of the content of this manuscript in Reger’s Gründlicher Bericht, but given a) the correspondence of the title’s terminology and syntax to that of the Testamentum; b) the aforementioned presence of Pfeffer’s words in the Thesaurus thesaurorum and another text describing the order’s magical activities (Himmlisches und übernatürliches Geheimnis des Geistes und der Seele der Welt); and c), the doctrinal and terminological commonalities of Pfeffer’s oeuvre with the Cabalistic sections of the Testamentum, it is highly likely that the manuscript in Reger’s inventory was a forebear of the order compendia analysed here.

Among those commonalities we find generic Pietist, Böhmian and Christian Cabalistic themes: the Weltgelehrten (those taught by the world),[57] Schriftgelehrten (those taught by texts)[58] and Pharisaic Sterngelehrten (those taught by the stars)[59] are guided by fallible human reasoning[60] and scholastic book-lore,[61] and are thus fully incapable of attaining a new Adamic body through spiritual rebirth,[62] of passing from this visible world into the inner Mysterium, of penetrating to ‘the Centre of the great spirit’ and achieving spiritual union with Jehovah.[63] Such union is the primary concern of ‘divine magic’, which utilises the seven Quellgeister (source-spirits) as a bridge between this ephemeral world and the eternal realm of triune divinity;[64] these spirits exist within the human microcosm as sealed ‘psychic qualities’, and their seven seals (cf. Revelations 5.1-5) are broken through the light of Christ as the initiate follows the aphorism of the prisci theologi: nosce te ipsum.[65] The (Joachimite) chiliastic dimensions of this spiritual process are evident in both Pfeffer’s work and the texts of the order.[66]

Figure 8. The book with seven seals: Gold- und Rosenkreuz manuscript (c.1760), Beinecke Library, Mellon MS 110 (A) and Ad 1ste Hauptstuffe Nr. 1 + Nr. 3 (Asiatic Brethren tables), Octagon Collection (B).

However, some commonalities are less generic. Thus the Gründlicher Bericht states that, just as higher angels instruct those beneath them, so the secret of the Urim and Thummim was passed down in an esoteric lineage among the prophets, who were practitioners of magia divina.[67] In another place in Pfeffer’s presumed oeuvre divine revelations in a speculum magicum divinum are mentioned.[68] At the end of his inventory, Reger also lists a number of manuscripts owned but not authored by Pfeffer ‘that have never been printed’: this includes a ‘manual’ of Heinrich Khunrath that is the likely source of the esoteric magical practices in question.[69]

This evidence suggests Pfeffer belonged to an esoteric lineage stretching from Khunrath to the later Gold- und Rosenkreuz. However, while the doctrines and practices described in the printed works associated with Pfeffer are certainly consonant with the worldview of the order’s Testamentum, should we attribute that text in its earliest form to Pfeffer? Let us compare the title of the Dresden Testamentum with the Testamentum that Reger claims is Pfeffer’s own work:

Tes t[d]ament[d]um [der Frader Aurae vel Rosae – als gewiße Extases oder geheime operationes, wo durch das Misterio er öffnet.] an die [unßere] Kinder der Kunst und Weiß[ys]heit[,] Göttlicher Magiae, [und] Englischer Cabalae und Natürlicher Philosophiae. [I. W. R. anno 580.]

Note that the last term in Pfeffer’s all-pervasive leitmotiv – göttliche Magia, englische Cabala und natürliche Philosophia[70] – has been removed, indicating the excision from Pfeffer’s Testamentum of material written under the rubric of ‘natural philosophy’ (i.e. the medical reflections to be found in Pfeffer’s surviving printed texts). However, there is insufficient data to draw a firm conclusion concerning the tract’s authorship. Notwithstanding the fact we are examining both texts through the lens of a number of redactions, stylistic dissimilarities between the Böhmian passages of the Testamentum and the work which can most safely be ascribed to Pfeffer – Das Buch Amor Proximi – raise the possibility that the Testamentum was a work redacted by, but not first authored by, Pfeffer.

If Pfeffer was a redactor of the Testamentum, was he a ‘Rosicrucian’? The above title comparison suggests the attribution of his Testamentum to ‘a brother[hood] of the golden or rosy [cross]’ was a later interpolation, as does the distinctive term Extases associated with pseudo-Gualdi (cf. infra). Indeed, in the Dresden codex the confusion of possessives and an incongruous full stop in the midst of the title still attest to this interpolation. While Pfeffer refers in Das Buch Amor Proximi to the ‘F. R. ✠’[71] – an abbreviation reminiscent of the Hessen-Darmstadt ‘Rosen✠er’[72] – in the manuscript titles of Reger’s inventory Pfeffer repeatedly addresses his own disciples with the Böhmian terminology of ‘children of lilies and roses’.[73] Once again, the data available does not support any definite conclusions concerning the ‘Rosicrucian’ affiliation of either Pfeffer or the Testamentum he authored/redacted.

Another interpolation evident from the comparison of titles is the conspicuous backdating of the Testamentum to ‘580’, which becomes a slightly more plausible ‘1580’ in the titles of the Thesaurus thesaurorum. Such backdating is characteristic of a number of ‘orphaned’ texts claimed by the Gold- und Rosenkreuz and related to Pfeffer’s oeuvre. By the mid-eighteenth century the Himmlisches und übernatürliches Geheimnis des Geistes und der Seele der Welt had been backdated to 1566 and ascribed to Trithemius; likewise, by the point of their publication in Erfurt in the mid-1730’s the Occulta philosophia, Uraltes chymisches Werck and Coelum reseratum chymicum had accrued pseudo-historical framing narratives.[74] That of the Occulta philosophia describing the conflict of its supposed author – Ludwig Conrad ‘Orvius’ of Berg – with the draconian Imperator of the Gold- und Rosenkreuz in the early seventeenth century is manifestly fictional;[75] by 1926 Scholem had already noted the Böhmian terminology utilized by the allegedly fourteenth-century author of the Uraltes chymisches Werck, ‘Abraham Eleazar’;[76] and the Coelum reseratum chymicum in its print and existing manuscript versions is backdated to 1612 in an attempt to portray its author as Johann Thölde (c.1565-c.1614), the publisher of the works of Basil Valentine (and thus demonstrate the priority of the order’s lineage in relation to the Rosicrucian manifestos). The latter two texts appeared under the guise of works that had been alluded to by earlier authors (Flamel,[77] Tolle[78]) but were never published, as did a further related text, the spurious ‘third book’ of Kirchweger’s Aurea catena Homeri:[79] in this manner one or more redactors have attached more illustrious names to unpublished material that originated in part with Pfeffer.

In the case of the order’s Testamentum, the most likely scenario given the available evidence is that the redactor: 1) was a resident of Utrecht; 2) wrote under the name of ‘Friedrich Gualdi’; 3) was a custodian of Pfeffer’s esoteric magical tradition; 4) worked at the hub of a large epistolary network of practicing alchemists and magicians; and 5), died in 1724. According to this scenario, the ‘pseudo-Gualdi’ in question was responsible for splicing Pfeffer’s Testamentum together with the laws of the fraternity associated with the true Friedrich Gualdi. The earliest version of these laws in exoteric circulation is an Italian manuscript housed at the Biblioteca Nazionale in Naples and dated to 1678.[80] A comparison of these Italian laws with those given in the three Testamentum codices reveals the insertion of idiosyncratic material designed to bring them into conformity with Pfeffer’s esoteric tradition:

a) the unveiling of a free-standing Urim during the neophyte initiation ceremony[81]

b) the appearance of ‘seven elders’ or Magi[82]

c) a reference to spiritual union with God through abnegation of the flesh[83]

d) a statement that the order’s secrets pertain to ‘magia’ and ‘Cabala’[84]

e) the addition of order meeting-houses in Amsterdam, Hamburg and ‘Ancona’ (Altona?) to the original meeting-house in Nuremberg[85]

The short pseudo-history of the Italian laws describes the reformation of the order in 1542-43.[86] In its stead the Testamentum supplies the much longer patriarchal pseudo-history I have briefly described; various fictional ‘events’ in the history of the order are also added to the laws, such as the exposure of brethren due to indiscretions with women and canting clerics.[87]

The Italian laws appear to belong to the alchemical and magical sect led by Friedrich Gualdi: the Cavallieri dell’ Aurea Croce (Knights of the Gold Cross), which constituted a conspiratorial cabal within high diplomatic and political circles in Venice. Notwithstanding their likely inclusion of hearsay and deliberate defamation, the Inquisitorial records refer to Gualdi as ‘a star that dominates Venice’ (presumably just as the sage dominates the stars),[88] and mention is made of an elixir produced from human semen by which the operator is ‘exalted to an angelic nature’ and becomes a ‘prophet dominating the aerial and subterranean spirits’.[89] These are summoned and subdued with the help of un libro di negromanzia containing their characters, legions and circles;[90] thus one diabolical spirit is said to be kept captive in a flask (cf. figure 6, lower left).[91] The legend of Gualdi’s longevity is also present in the records.[92] This is attributable to the Philosophers’ Stone he possesses: thus most of the Italian laws (if they indeed belong to Gualdi’s ‘high sect’)[93] are directed toward the maintenance of secrecy and the correct handling of this lapis, which takes powdered, liquid and solid forms. There are also references to a (magical or ecstatic?) riversioni di spiriti as well as natural magical artefacts such as ever-burning lights.[94]

What was the relationship of the Cavallieri dell’ Aurea Croce to the Germanic Gold- und Rosenkreuz associated with Pfeffer’s esoteric tradition? There is little indication in either the Inquisitorial records, the Italian laws or Gualdi’s genuine works[95] of Pietist, Böhmian and Christian Cabalistic themes or terminology. Nevertheless, angelification via a seminal tincture (alchemically assisted theurgy)[96] and pseudo-Solomonic demon-binding are consonant with the practices described in the esoteric manuscript literature of the Gold- und Rosenkreuz.[97] The twofold division of the order into ‘brethren of the golden cross’ (signified by a red cross) and ‘brethren of the rosy cross’ (signified by a green cross) alluded to in all existing versions of the order’s laws may indicate the amalgamation of the alchemically oriented Italian ‘Philosophers of the Gold Cross’[98] with a Rosicrucian tradition based in Nuremberg and represented by Gualdi.[99] Although Gilly argues that the laws of the order were ‘originally written in Italian by Roman Catholics’, and that their content is ‘of good Catholic stock’,[100] the Naples manuscript clearly states that the order’s headquarters (la casa maggiore) are in Nuremberg, residence of the imperatore (quite possibly Gualdi, the ‘prince of the high sect’).[101] Moreover, Gualdi is repeatedly referred to in the Inquisitorial records as a German and ‘native of Augsburg’.[102] Nor are Richter’s laws a translation of the Naples text, as Gilly asserts.[103] Rather, they are derived from a Protestant German manuscript (RQ2); therefore it is too early to conclude the laws are an ‘Italian import product’.[104]

Whether it existed beforehand or not, the first hard evidence for the doctrinal and organisational continuity of the Cavallieri dell’ Aurea Croce with the Germanic Gold- und Rosenkreuz is to be found in the figure of pseudo-Gualdi – a follower of both Gualdi and Pfeffer who (according to the aforementioned scenario) was responsible for those transformations in the order’s grade system and cultus that are manifestly derived from Pfeffer’s esoteric tradition.[105] After Gualdi’s death, this pseudo-Gualdi more or less opportunistically traded on the mystique surrounding Gualdi and his life-giving elixir.[106] Thus the Amsterdam manuscript of Pfeffer’s ‘orphaned’ Cabala et philosophia naturae et artis is ascribed to ‘Fridericus Gualdianus’, and has a preface signed in Utrecht in ‘1678’ – yet the real Gualdi was still in Venice in that year.[107] Furthermore, two Pietistically tinged letters describe a Dutch ‘Friedrich Gualdianus’ undertaking a mission in September 1721 on behalf of the ‘Brüderschafft der Rosen-Creutzer’ to collect secret manuscripts belonging to a recently deceased ‘brother’: a two-part Schlüssel der wahren Weisheit (Key to True Wisdom) and Der güldene Begriff (The Golden Compendium), the latter of which forms the bulk of the fourth book of the Darmstadt Thesaurus thesaurorum.[108] While the veracity of the narrative presented in these letters is by no means assured, pseudo-Gualdi refers to himself therein as a Dutchman, and describes a journey from Utrecht to Nuremberg, Augsburg and Biberbach, where the brother’s widow awaits him with the said order manuscripts.[109] Another tract ascribed to ‘Prinz Utasop a.k.a. Friedrich Gualdianus’ and dated to 1722 is to be found in a collection of thirteen ‘letters’ from pseudonymous brethren of the ‘Fradernität Rosee Crucis Aurea’; purportedly written from Utrecht (home to the ‘Imperator’), Limbourg, Helsingør, Wolfenbüttel, Hamburg, Maastricht and Lübeck, they give the impression of an epistolary network used to share laboratory experience and exchange alchemical recipes for the creation of tinctures from the four realms.[110] One manuscript version of these letters is bound together with the aforementioned laws of the fraternity; another is bound with the spurious ‘third’ book of Kirchweger’s Aurea catena Homeri, which in its printed version is also dated ‘Utrecht the 18th of October 1654’.[111]

The identity of pseudo-Gualdi is addressed by the Swiss alchemist Friedrich Mumenthaler (1700-1777), who is better known by his pseudonym ‘Hermann Fictuld’.[112] Mumenthaler was the customs inspector and public treasurer of Langenthal, a small but prosperous trading centre some 50 kilometres south of Basel; to the east of this country town he built a (now ruined) manor-house he named Sonnenberg (solar mountain), where it was rumoured he engaged in alchemical and magical experiments.[113] In his Probier-stein Mumenthaler describes two men writing under the name of Friedrich Gualdi: 1) ‘Fredricus Gualdus der I’, a German resident in seventeenth-century Venice and Vicenza who wrote tracts in both Italian and German; and 2), ‘Fredricus Gualdus der II’, who wrote letters under the name of the first Gualdi and who was a personal friend of Mumenthaler.[114] This second pseudo-Gualdi was a ‘descendant and disciple’ of the first Gualdi who adopted his name and title ‘out of thankfulness and high respect for his patron’, and who spent his days visiting and corresponding with other disciples (hence, perhaps, his alleged journey to Augsburg, Nuremberg and Biberbach).[115] According to Mumenthaler, pseudo-Gualdi died in 1724 – a date confirmed by the alchemist Johann Gottfried Meister, who adds that he died in ‘N.’, where the town administration took possession of his effects.[116] The widespread dissemination and publication of order texts in the years that followed may well be contingent upon this fact.

In this manner Mumenthaler lays to rest the ubiquitous and persistent legend of Friedrich Gualdi’s remarkable longevity. It is probable that one and the same individual was responsible for putting the name of ‘Friedrich Gualdi of Utrecht’ to both his own letters and Pfeffer’s Cabala et philosophia naturae et artis; likewise, it is probable that this same pseudo-Gualdi was responsible for marrying Pfeffer’s Testamentum an die Kinder der Kunst und Weißheit with what appear to be the laws of Gualdi’s fraternity.

While it cannot be adduced as proof, the date of origin of the order’s Testamentum does not speak against this probability. Gilly dates the text to 1737;[117] yet the terminus ante quem for the creation of the Vienna Testamentum is 1735, the year in which it was acquired by the Silesian nobleman Johann Adalbert Prinz de Buchau.[118] Its provenance is southern German,[119] and the Hebrew patriarchal pseudo-histories of all copies of the Thesaurus thesaurorum are derived from a lost common source of this manuscript (TeQ2).[120] The Dresden Testamentum is part of the aforementioned cache of order manuscripts donated to the Kursächsische Archiv des geheimen Konsiliums (1702-1834; today the Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek or ‘SLUB’); its distinctive Low German orthography links it to the SLUB manuscript of the letters of pseudo-Gualdi and his twelve fellow ‘brethren’.[121] Another tract in the same cache and from the same hand was acquired by ‘J. L. V.’ from ‘Geheimer Rath Sepach’ (Ludwig Alexander von Seebach, 1668-1731[122]) in 1729.[123] As for the Hamburg Testamentum, it once belonged to Rudolph Johann Friedrich Schmid (1702-1761), an alchemist active in Jena, Copenhagen, Vienna and Hamburg whose extensive manuscript collection was acquired by the Hamburg city library upon his death.[124] It is possible that Schmid himself was a member of the Gold- und Rosenkreuz: not only do his experiments on the alchemical reanimation of corpses resemble those of the Testamentum he possessed,[125] but at some point prior to 1742 he assured an acquaintance that Freemasonry was ‘united with magic and alchemy’ (the earliest indication of the fateful merger of Rosicrucianism with Freemasonry that I am aware of).[126] In any case, there are a number of good reasons to believe the Hamburg manuscript Schmid once owned is the earliest of the three existing versions of the Testamentum: for example, both the Dresden and Vienna manuscripts mistake Das Buch der Weißheit ascribed to pseudo-Thölde in the Hamburg Testamentum for the deuterocanonical Wisdom of Solomon.[127] Furthermore, the sixth page of the Hamburg manuscript gives the very plausible date ‘1708’.

It is unclear if the emergence of the order’s Testamentum (i.e. TeQ1) coincides with the rise of order ceremonial activity involving the use of the Urim, or indeed with the rise of the grade structure of the later Gold- und Rosenkreuz and its seven ‘Magi’. However, the Testamentum and Thesaurus thesaurorum do not present us with the mere literary form of ceremony, or a fictional brotherhood such as that apparently portrayed in the Rosicrucian manifestos. Nor was the order a purely virtual entity, notwithstanding the evident centrality to its operation of the epistolary network inherited from Gualdi by pseudo-Gualdi of Utrecht, and subsequently by Imperator Tobias Schultz (1686-c.1770) of Amsterdam.[128] I am not aware of the survival of any electrum magicum artefacts utilised by the Gold- und Rosenkreuz; of the pendant Urim utilised by the Asiatic Brethren, the ‘old, true original’ was once said to be held in Vienna.[129] But there is credible historical evidence of ceremonial practice among European ruling elites that contradicts Geffarth’s suggestion that the highest grade of the Gold- und Rosenkreuz was a purely literary expression of the order’s ideals.[130] This evidence is from the quasi-Masonic phase of the order and includes both the aforementioned initiation of Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia,[131] as well as the ceremonies of the Metatronisten centred upon Friedrich Wilhelm’s first cousin Duke Karl of Södermanland (later Karl XIII of Sweden).[132] The latter group’s name is associated with the magia Metatrona of the Gold- und Rosenkreuz;[133] a manuscript in Duke Karl’s own hand shows a floor-plan of a Sanktuarium secreted at the heart of the Swedish royal palace, complete with Menorah, incense altar and Holy of Holies.[134] There white-robed brethren – including the noted spirit mediums Gustaf Björnram and Henrik Gustaf Ulfvenklou – employed the ‘Urim and Thummim’ to ‘clearly discern the precise character and nature of a man, as if in a mirror’.[135]

Figure 9. Ceremonial magical architecture of Duke Karl of Södermanland: the Sanktuarium (from von Schinkel and Bergman, Minnen ur Sveriges nyare historia) (A) and the spirit-summoning temple of Abramelin (Magia divina, Svenska Frimurare Ordensbiblioteket, MS 13.106 Mystik; image courtesy of Tommy Westlund, Sodalitas Rosae+Crucis & Solis Alati).

Gilly has argued that ‘the Rosicrucians experienced their cultural nadir’ under the Gold- und Rosenkreuz, having replaced the noble reform programme of the original manifestos with ‘empty ceremony and hollow alchemical phraseology’.[136] My research under the patronage of Thomas Hakl has painted a very different picture of the order. The cultus of the Gold- und Rosenkreuz has its origins in an esoteric tradition predating the manifestos; amongst this tradition’s guardians and practitioners we find a preponderance of manual workers (miners are prominently represented)[137] with an enchanted experience of the natural order, a pious disregard for conformity and an ‘exilic’ Gnostic attitude linked to an imminentist eschatology.[138] In their marginalised form of Christianity, interaction with lower spirits is an essential step on a path to God that at once reverses and consummates the cosmogony; for this reason their faith has all too easily been condemned as diabolical heresy, enthusiastic insanity or irrational absurdity by those who have failed to subjugate (and are therefore ruled by) their own demons. While there is no evidence of any continuity of organisation between the Gold- und Rosenkreuz and the early network in Gießen, Ulm and Marburg ostensibly self-identifying as ‘Rosicrucian’,[139] both were inheritors of an anti-institutional inspirationist tendency – present, albeit obscured, in the manifestos – promoting the irenicism of the radical Reformers (Franck, Weigel) and drawn to the addressative magic of the Paracelsians, Christian Cabalists and the grimoire tradition. Flowing forward in time to the Golden Dawn and Thelema, this is a current of esoteric praxis that is not always visible to the intellectual historian or historian of ideas, but that is nevertheless of considerable significance to the history of religion in Europe.

Bibliography

Manuscripts

Ad 1ste Hauptstuffe Nr. 1 + Nr. 3. Octagon Collection.

Adnotationes Hermeticae, Fasciculus III. Vienna: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. Ser. n. 4135 Han.

Arcana divina. Yale: Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Mellon MS 88.

Aurum Seculum ChurFürst. Augusti und Christano. Primi. mid Eignen henden gearbeidet. Dresden: Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, MS e 8/1.

Das zweyte Silentium Dei in des Königs Salomonis des Weisen paradiessischen Lustgarten. Yale: Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Mellon MS 136.

De magia divina oder Caballistischer Geheimnüsse. London: Wellcome Library, MS 4808, pp. 223-263.

Der güldene Begriff. Dresden: Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, MS N 166.

Geheime Manipulatio etlicher Rosen- und Gulden Creuzer. Amsterdam: Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica, MS M 203.

γνῶθι σεαυτόν seu noscete ipsum: Sextus sapientiae liber verus ac genuinus. Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Kiesewetteriana 1 d (1777).

Gualdi, Friedrich. Philosophia hermetica, overo vera, reale e sincera descriggione della pierra filosofica. New Haven: Yale University, Beinecke Library, MS 131, ff. 1-41.

Gualdi, Friedrich [pseud.]. Cabala et philosophia naturae et artis: Fridericus Gualdianus, ein geberner orientalischer Prinz u. Bluthsverwander des Keyssers von Marocco 1698. The Hague: Bibliotheek van de Orde van Vrijmetselaren, MS 190 E 55.

Gualdi, Friedrich [pseud.]. Fridericus Gualdianus. Ein geborener Orientalischer Printz und Bluths verwandter des Keysers von Marocco, Cabala et philosophia naturae et artis 1698. Amsterdam: Bibliotheca Philosophia Hermetica, MS M 217.

Haussen, Johann Salomon and Tobias Schultz. Briefwechsel Tobias Schultzens, Ehelichs und Haußens. Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Kiesewetteriana 30.

I. N. R. I. Magia divina, die Gott der Herr nur seinen Kindern vorbehalten hat, worinnen unaussprechliche Wunder zu sehen, von Wort zu Wort beschrieben. The Hague: Bibliotheek van de Orde van Vrijmetselaren, MS 240 A 43.

Jesvs et Maria et Ioseph. London: Wellcome Library, MS 259.1, ff. 1 recto – 2 verso.

Kabbalistische Geheimnisse de magia divina worinnen allerhand rare unerhoerte Dinge enthalten. Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Kiesewetteriana 18.

Khunrath, Heinrich, Consilium de Vulcani magica fabrefactione armorum Achillis Græcorum omnium fortissimo et cedere nescii. Stockholm: Kungliga Biblioteket MS Rål 4.

L. B. V. D. Testamentum societatis aureae & roseae crucis darinnen gewiße geheime Operationes alß große Mysteria unseren Kindern u. Schülern Magiae divinae & Cabalae eröffnet werden. I. W. R. Hamburg: Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg, Cod. alchim. 750.

‘Liber Theophrasti de septem stellis’, in Septimus sapientiae: Liber verus ac genuinus. Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Kiesewetteriana 1 e, pp. 180-343.

Magia divina die Gott der Herr nur seinen Kindern vorbehalten hat, worinnen unaussprechliche Wunder zu sehen, von Wort zu Wort beschrieben. Dresden: Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, MS N 166.

Magia divina. Stockholm: Svenska Frimurare Ordensbiblioteket, MS 13.106 Mystik.

Orvius, Ludwig Conrad. Occulta philosophia. Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Kiesewetteriana 24.

‘Osservationi inviolabibili [sic] da osservarsi dalli Fratelli dell’ Aurea Croce, ò vero dell’ Aurea Rosa precedenti la solita professione’. In Andreas Segura, Filosofia filosofica [sic]. Naples: Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli, Cod. XII-E-30, ff. 226 recto – 242 verso.

Paracelsus [pseud.]. ‘Dei [sic] magia oder magia divina seu praxis Cabulae albae et naturalis’, in Septimus sapientiae: Liber verus ac genuinus. Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Kiesewetteriana 1 e, pp. 426-572.

Paracelsus [pseud.]. Universal Anleitung. Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Kiesewetteriana 25 d.

Schlüssel der wahren Weisheit. Dresden: Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, MS N 162.

Sponte comparuit Francesci Giusti contra Federicum Gualdum et sequacis de magicis artibus. Venice: Archivio di Stato di Venezia, Sant’Uffizio, Processi, MS b 119.

Tabulae theosophiae Cabbalisticae. London: British Library, Sloane MS 181.

Tesdamendum der Frader Aurae vel Rosae [sic] – als gewiße Extases oder geheime operationes, wo durch das Misterio er öffnet. an unßere Kinder der Kunst und Weysheit, Göttlicher Magia und Englischer Cabala. I. W. R. anno 580. Dresden: Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, MS N 158.

Testamentum der Fraternitet Rosae et Aureae Crucis, alß gewise Exstases oder geheime Operationes, wodürch das Mysterium eröffnet an unsere Künder der Weißheit göttl. Magiae und Englischer Cabalae. J. W. R. Anno 580. Vienna: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. Ser. n. 2897 Han.

Thesaurus Thesaurorum a Fraternitate Rosae et aureae Crucis Testamento consignatus, et in Arcam Foederis repositus suae Scholae Alumnis, et Electis Fratribus. anno. MDLXXX. Octagon Collection.

Thesaurus thesaurorum à fraternitate roseae et aureae crucis testamento consignatus, et in arcam foederis repositus suae scholae tyronibus, et alumnis fratribus. Anno MDLXXX. 1580. Stuttgart: Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart, Cod. theol. et phil. Qt 514.

Thesaurus thesaurorum à fraternitate roseae et aureae crucis testamento consignatus, et in arcam foederis repositus suae scholae alumnis et electis fratribus. Anno MDLXXX. Darmstadt: Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Darmstadt, Hs 3262.

Thölde, Johann [pseud.]. Schrifftliche Unterrichtung der wahren Weißheit von der F. R. C. London: Wellcome Library, MS 4808.

Trithemius [pseud.]. Heimliches und uebernatuerliches Geheimnis des Geistes und der Seele der Welt, 1506. Überlingen: Leopold-Sophien-Bibliothek, MS 234.

Trithemius [pseud.]. Himmlisches und übernatürliches Geheimnis des Geistes und der Seele der Welt und von der natürlichen Magia. Amsterdam: Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica, MS M 217.

von Woellner, Johann Christoph. Johann Christoph von Woellner to Johann Rudolf von Bischoffwerder, 22 April 1783. Berlin: Geheime Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, BPH Rep. 48 – König Friedrich Wilhelm II, Nr. 8, Bd. 1, ff. 2o recto – 21 recto.

Books

Abafi-Aigner, Ludwig. ‘Die Entstehung der neuen Rosenkreuzer’, Die Bauhütte 36, 11 (1893), 81-85.

‘Authentische Nachricht von den eigentlichen Grundsätzen der wahren Rosenkreutzer, und wo sich die Originalnachrichten davon befinden’, Der Deutsche Zuschauer 16, 6 (1787), pp. 198-208.

Arnold, Gottfried. Fortsetzung und Erläuterung… der unpartheyischen Kirchen- und Ketzer-Historie. Frankfurt am Main: Thomas Fritschens sel. Erben, 1729.

Arnold, Gottfried. Unpartheyische Kirchen- und Ketzer-Historie, vol 2. Frankfurt am Main: Thomas Fritsch, 1700.

Ayscough, Samuel. A Catalogue of the Manuscripts Preserved in the British Museum hitherto Undescribed, vol 2. London: John Rivington, 1782.

Boella, Alessandro and Antonella Galli (eds.). L’alchimia della confraternita dell’Aurea Rosacroce. Rome: Edizioni Mediterranee, 2013.

Böhme, Jacob. Informatorium novissimorum, oder Unterricht von den Letzten Zeiten, vol 13 of Theosophia Revelata. S.l.: s.n., 1730.

Böhme, Jacob. Theosophische Schriften. Amsterdam: Heinrich Betke, 1675.

Brecht, Martin. ‘Die deutschen Spiritualisten des 17. Jahrhunderts’, in Der Pietismus vom siebzehnten bis zum frühen achtzehnten Jahrhundert, 205-240. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1993.

Breckling, Friedrich. ‘Mehrere Zeugen der Wahrheit’, in Gottfried Arnold, Fortsetzung und Erläuterung… der unpartheyischen Kirchen- und Ketzer-Historie, 1089-1110. Frankfurt am Main: Thomas Fritschens sel. Erben, 1729.

Breckling, Friedrich. Autobiographie: ein frühneuzeitliches Ego-Dokument im Spannungsfeld von Spiritualismus, radikalem Pietismus und Theosophie, ed. Johann Anselm Steiger. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 2005.

Curieuse Untersuchung etlicher Mineralien, Thiere und Kräuter. S.l.: s.n., 1703.

Die alten Matrikeln der Universitaet Strassburg 1621 bis 1793, vol 1, ed. Gustav Carl Knod. Strasbourg: Karl J. Trübner, 1897.

Die Brüder St. Johannis des Evangelisten aus Asien in Europa, oder die einzige wahre und ächte Freimaurerei. Berlin: Johann Wilhelm Schmidt, 1803.

Dreyzehn geheime Briefe von dem großen Geheimniße des Universals und Particulars der goldenen und Rosenkreutzer. Leipzig: Adam Friedrich Böhme, 1788.

Duveen, Denis. Bibliotheca alchemica et chemica. London: Dawsons of Pall Mall, 1965.

Edelmann, Johann Christian. Joh. Chr. Edelmann’s Selbstbiographie, ed. Karl Close. Berlin: Karl Wiegandt, 1849.

Eleazar, Abraham [pseud.]. R. Abrahami Eleazaris Uraltes Chymisches Werck, 2 vols. Erfurt: Augustinus Crusius, 1735.

Faivre, Antoine. Access to Western Esotericism. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994.

Feßler, Ignaz Aurelius. Fessler’s sämmtliche Schriften über Freymaurerey. Wirklich als Manuscript für Brüder. Berlin: s.n., 1801.

Fictuld, Hermann [Friedrich Mumenthaler]. Azoth et ignis… Aureum vellus. Leipzig: Michael Blochberger, 1749.

Fictuld, Hermann [Friedrich Mumenthaler]. Der längst gewünschte und versprochene chymisch-philosophische Probier-Stein, 2 vols. Frankfurt: Veraci Orientali Wahrheit und Ernst Lugenfeind, 1753.

Fictuld, Hermann [Friedrich Mumenthaler]. Wege zum Grossen Universal, oder Stein der Alten Weisen. S.l.: s.n., 1731.

Forshaw, Peter. ‘“Behold, the dreamer cometh”: Hyperphysical Magic and Deific Visions in an Early Modern Theosophical Lab-Oratory’, in Joad Raymond (ed.), Conversations with Angels: Essays towards a History of Spiritual Communication, 175-200. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Geffarth, Renko. Religion und arkane Hierarchie: Der Orden der Gold- und Rosenkreuzer als geheime Kirche im 18. Jahrhundert. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

Gilly, Carlos and Cis van Heertum. Magia, alchimia, scienza dal ‘400 al ‘700. L’influsso di Ermete Trismegisto, vol 2. Florence: Centro Di, 2005.

Gilly, Carlos. ‘Vom ägyptischen Hermes zum Trismegistus Germanus’, in Konzepte des Hermetismus in der Literatur der Frühen Neuzeit, ed. Peter-André Alt and Volkhard Wel, 71-131. Göttingen: V&R Unipress, 2010.

Gmelin, Johann Friedrich. Geschichte der Chemie, vol 2. Göttingen: Johann Georg Rosenbusch, 1798.

Häll, Jan. I Swedenborgs labyrint. Studier i de gustavianska swedenborgarnas liv och tänkande. Stockholm: Atlantis, 1995.

Heijting, Willem. ‘Hendrick Beets, uitgever voor de Duitse Böhme-aanhangers in Amsterdam’, in Willem Heijting, Profijtelijke boekskens: boekcultuur, geloof en gewin, 209-243. Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren, 2007.

Hermetisches A. B. C. derer ächten Weisen, vol 3. Berlin: Christian Ulrich Ringmacher, 1779.

Herverdi, Joseph Ferdinand. Erklärung des mineralischen Reichs. Berlin: Arnold Wever, 1783.

Herzog, Katharina Christiane. ‘Mythologische Kleinplastik in Meißener Porzellan 1710-1775’. Doctoral dissertation, Universität Passau, 2012.

Hochhuth, Karl. ‘Mitteilungen aus der protestantischen Secten-Geschichte in der hessischen Kirche’, Zeitschrift für die historische Theologie 32, 1 (1862), 86-159.

Hochhuth, Karl. ‘Mitteilungen aus der protestantischen Secten-Geschichte in der hessischen Kirche’, Zeitschrift für die historische Theologie 33, 2 (1863), 169-262.

Humbertclaude, Eric. Federico Gualdi à Venise: fragments retrouvés (1660-1678). Paris: L’Harmattan, 2010.

Jugel, Johann Gottfried. Geometria subterranea. Leipzig: Johann Paul Kraus, 1773.

Juterczenka, Sünne. Über Gott und die Welt: Endzeitvisionen, Reformdebatten und die europäische Quäkermission in der Frühen Neuzeit. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008.

Khunrath, Heinrich. Amphitheatrum sapientiae aeternae. Hanau: Erasmus Wolfart, 1609.

Khunrath, Heinrich. De igne Magorum philosophorumque secreto externo et visibili. Strasbourg: Zetzner, 1608.

Kiesewetter, Karl. ‘Die Rosenkreuzer, ein Blick in dunkele Vergangenheit’, Sphinx: Monatsschrift für die geschichtliche und experimentale Begründung der übersinnlichen Weltanschauung auf monistischer Grundlage 1 (1886), 42-54.

Kirchweger, Anton. Aurea catena Homeri. Frankfurt: Johann Georg Böhme, 1723.

Kirchweger, Anton. Aurea catena Homeri. Jena: Christian Henrich Cuno, 1757.

Klenk, Heinrich. ‘Ein sogenannter Inquisitionsprozeß in Gießen anno 1623’, Mitteilungen des Oberhessischen Geschichtsvereins 49 (1965), 39-60.

Kopp, Hermann. Die Alchemie in älterer und neuerer Zeit: ein Beitrag zur Culturgeschichte, vol 1. Heidelberg: Carl Winter, 1886.

La critica della morte. Colonia: s.n., 1694.

Lekeby, Kjell. Gustaviansk Mystik – alkemister, kabbalister, magiker, andeskådare, astrologer och skattgrävare i den esoteriska kretsen kring G. A. Reuterholm, hertig Carl och hertiginnan Charlotta 1776 – 1803. Södermalm: Vertigo Förlag, 2010.

Lindner, Johann Gotthelf. Ganz besonderer und merkwürdiger Brief an die Herren Herren [sic] Hohen unbekannten Obern Gold- und Rosenkreuzer, Alten Systems in Deutschland und anderen Ländern. S.l.: s.n., 1820.

Magia divina, oder gründ- und deutlicher Unterricht, von denen fürnehmsten Caballistischen Kunst-Stücken derer Alten Israeliten Welt-Weisen, und Ersten, auch noch einigen heutigen wahren Christen. S.l.: L. v. H., 1745.

Mazal, Otto and Franz Unterkircher. Katalog der abendländischen Handschriften der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, ‘Series Nova’ (Neuerwerbungen), vol 2 (Cod. ser. n. 1601-3200). Wien: Prachner, 1963.

Meister, Johann Gottfried. Curiöse historische Nachricht von Verwandlung der geringen Metalle in Bessere. Frankfurt am Main: s.n., 1726.

Meyer-Salzmann, Marta. Langenthaler Handwerksärzte und Apotheker im 18. Jahrhundert und ein Blick ins 19. Jahrhundert. Langenthal: Stiftung zur Förderung wissenschaftlich-heimatkundlicher Forschung über Dorf und Gemeinde Langenthal, 1984.

Michelmann, Jakob. Der Wunder-volle und heiliggeführte Lebens-Lauf des auserwehlten Rüstzeugs und hochseligen Mannes Gottes, Johann Georg Gichtels, vol 7 of Johann Georg Gichtel, Theosophia practica. Leiden: s.n., 1722.

Moller, Johann. Cimbria literata, vol 1. Copenhagen: Orphanotrophius Regius, 1744.

Mulsow, Martin. ‘You Only Live Twice: Charlatanism, Alchemy, and Critique of Religion, Hamburg, 1747–1761’, Cultural and Social History 3 (2006), 273-286.

Münter, Friedrich. Authentische Nachricht von den Ritter- und Brüder-Eingeweihten aus Asien: zur Beherzigung für Freymaurer. Copenhagen: Profft, 1787.

Olearius, Gottfried. Halygraphia topo-chronologica. Leipzig: Johann Wittigau, 1667.

Orvius, Ludwig Conrad. Occulta philosophia, coelum sapientum et vexatio stultorum. In der Insul der Zufriedenheit [Erfurt]: Augustinus Crusius, 1737.

Paracelsus. Astronomia magna, vol. 12 of Sämtliche Werke, ed. K. Sudhoff. Munich: Oldenbourg, 1933.

Paracelsus. Werke, vol 5, ed. Will-Erich Peuckert. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1968.

Paracelsus [pseud.]. Archidoxis magica, in Paracelsus, Sämtliche Werke, vol 14, ed. K. Sudhoff, 437-498. Munich: Oldenbourg, 1933.

Patai, Raphael. The Jewish Alchemists: A History and Source Book. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Paulus, Julian. ‘The Collection of Alchemical Books and Manuscripts in Hamburg’, in Alchemy Revisited: Proceedings of the International Conference on the History of Alchemy at the University of Groningen, 17-19 April 1989, ed. Z. R. W. M. von Martels, 245-249. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1990.

[Pfeffer, Ulrich]. Das Buch Amor Proximi: Geflossen aus dem Oehl der Göttlichen Barmhertzigkeit. The Hague: Pieter Hagen, 1686.

Reger, Georg Ernst Aurelius. Nosce te ipsum physico-medicum. S.l.: s.n., c.1705.

Reger, George Ernst Aurelius. Gründlicher Bericht auff einige Fragen. Hamburg: Georg Wolff, 1683.

Renatus, Sincerus [Samuel Richter]. Die wahrhaffte und vollkommene Bereitung des Philosophischen Steins der Bruderschaft aus dem Orden des Gulden- und Rosen-creutzes. Breslau: Fellgiebels seelige Wittwe und Erben, 1710.

Rottman, Franz. Treuhertzige Vermahnung in diesen itzigen gefährlichen/ doch wunderbahrlichen Zeiten… Hamburg: Georg Wolff, 1680.

Schmidt-Biggemann, Wilhelm. Apokalypse und Philologie. Göttingen: V&R Unipress, 2006.

Scholem, Gershom. ‘Zu Abraham Eleazars Buch und dem Esch Mezareph’, Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums 70, 3 (1926), 202-209.

Schröder, Friedrich. Neue alchymistische Bibliothek für den Naturkundiger, vol 1. Frankfurt am Main: Heinrich Ludwig Brünner, 1772.

Schultze, Johannes. Forschungen zur brandenburgischen und preussischen Geschichte. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1964.

Scott, Edward. Index to the Sloane Manuscripts in the British Museum. London: William Clowes and Sons, 1904.

Semler, Johann Salomon. Unparteiische Samlungen zur Historie der Rosenkreuzer, vol 2. Leipzig: Georg Emanuel Beer, 1787.

Sinapius, Johannes. Schlesische Curiositäten, vol 2. Leipzig: Michael Rohrlach, 1728.

Söldner, Johann Anton. Keren Happuch, Posaunen Elia des Künstlers, oder deutsches Fegefeuer der Scheidekunst. Hamburg: Libernickel, 1702.

Sturzen-Becker, Oscar Patric. Reuterholm efter hans egna memoirer. Stockholm: s.n., 1862.

Telle, Joachim. ‘Eine deutsche Alchimia Picta des 17. Jahrhunderts: Bemerkungen zu dem Vers/Bild-Traktat von der Hermetischen Kunst von Johann Augustin Brunnhofer und zu seinen kommentierten Fassungen im Buch Der Weisheit und im Hermaphroditischen Sonn- und Monds-Kind’, Aries 4, 1 (2004), 3-23.

Thölde, Johann [pseud.]. J. G. Toeltii, des welt-berühmten Philosophi Coelum reseratum chymicum. Erfurt: Carl Friedrich Jungnicols hinterlassene Wittwe, 1737.

Tilton, Hereward. ‘Alchymia Archetypica: Theurgy, Inner Transformation and the Historiography of Alchemy’, in Transmutatio: La via ermetica alla felicità (Quaderni di Studi Indo-Mediterranei, vol 5), ed. Daniela Boccassini and Carlo Testa, 179-215. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso, 2012.

Tilton, Hereward. ‘Of Electrum and the Armour of Achilles: Myth and Magic in a Manuscript of Heinrich Khunrath (1560-1605)’, Aries: Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism 6, 2 (2006), 117-157.

Tilton, Hereward. ‘Of Ether, Entheogens and Colloidal Gold: Heinrich Khunrath and the Making of a Philosophers’ Stone’, in Aaron Cheak (ed.), Alchemical Traditions: From Antiquity to the Avant-Garde, 355-422. Melbourne: Numen Books, 2013.

Tirinus, Jacobus. In universam Sacram Scripturam commentarius, vol 2. Venice: Nicolai Pezzana, 1760.

Tolle, Jacob. Manuductio ad coelum chemicum. Jena: Johann Christoph Crökern, 1752.

Tolle, Jacob. Sapientia insaniens. Amsterdam: Janssonius van Waesberge, 1689.

Toxites, Michael. Onomastica II. Strasbourg: Bernhard Jobin, 1574.

Trithemius [pseud.]. Wunder-Buch von der göttlichen Magie, ed. Johann Scheible. Passau [Stuttgart]: [Johann Scheible], 1506 [1857].

Trois traitez de la philosophie naturelle non encore imprimez. Paris: Guillaume Marette, 1612.

van Dam, Cornelis. The Urim and Thummim: A Means of Revelation in Ancient Israel. Warsaw: Eisenbrauns, 1997.

von der Recke, Elisa. Nachricht von des berüchtigten Cagliostro Aufenthalte in Mittau, im Jahre 1779. Berlin: Friedrich Nicolai, 1787.

von Plumenoek, Carl Hubert Lobreich [Bernhard Joseph Schleiß von Löwenfeld]. Geoffenbarter Einfluß in das allgemeine Wohl der Staaten der ächten Freymäurerey. Amsterdam [Regensburg]: s.n., 1777.

von Sabor, Chrysostomus Ferdinand. Practica naturae vera. Nuremberg: Getruckt auf Kosten der Rosencreutzer Brüderschafft, 1721.

von Schinkel, Bernt and Carl Bergman. Minnen ur Sveriges nyare historia, vol 3. Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & Söner, 1853.

von Vanderbeeg, I. C. Manuductio Hermedico-philosophica. Hof: Johann Ernst Schultz, 1739.

von Woellner, Johann Christoph. Der Signatstern oder die enthüllten sämmtlichen sieben Grade der mystischen Freimaurerei nebst dem Orden der Ritter des Lichts, vol 2. Berlin: C. G. Schöne, 1803.

Waite, Arthur Edward. The Brotherhood of the Rosy Cross. London: William Rider & Son, 1924.

[1] Thesaurus thesaurorum à fraternitate roseae et aureae crucis testamento consignatus, et in arcam foederis repositus suae scholae tyronibus, et alumnis fratribus. Anno MDLXXX. 1580. Stuttgart: Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart, Cod. theol. et phil. Qt 514 (henceforth MS Stuttgart); Thesaurus thesaurorum à fraternitate roseae et aureae crucis testamento consignatus, et in arcam foederis repositus suae scholae alumnis et electis fratribus. Anno MDLXXX. Darmstadt: Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Darmstadt, Hs 3262 (henceforth MS Darmstadt).

[2] Testamentum der Fraternitet Rosae et Aureae Crucis, alß gewise Exstases oder geheime Operationes, wodürch das Mysterium eröffnet an unsere Künder der Weißheit göttl. Magiae und Englischer Cabalae. J. W. R. Anno 580. Vienna: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. Ser. n. 2897 Han (henceforth MS Vienna); Tesdamendum der Frader Aurae vel Rosae [sic] – als gewiße Extases oder geheime operationes, wo durch das Misterio er öffnet. an unßere Kinder der Kunst und Weysheit, Göttlicher Magia und Englischer Cabala. I. W. R. anno 580. Dresden: Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, MS N 158 (henceforth MS Dresden); L. B. V. D. Testamentum societatis aureae & roseae crucis darinnen gewiße geheime Operationes alß große Mysteria unseren Kindern u. Schülern Magiae divinae & Cabalae eröffnet werden. I. W. R. Hamburg: Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg, Cod. alchim. 750 (henceforth MS Hamburg).

[3] Hence MS Octagon, 54-60/95-96 = Arcana divina. Yale: Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Mellon MS 88 (c.1725), ff. 10 verso – 16 verso/41 recto – 41 verso. Material from MS Octagon, 61-76 is also to be found, abbreviated and dispersed, in this version of the Arcana divina. Other members of the Arcana divina family of manuscripts include: pseudo-Paracelsus, Universal Anleitung. Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Kiesewetteriana 25 d (1767; Johann Haussen scripsit); Das zweyte Silentium Dei in des Königs Salomonis des Weisen paradiessischen Lustgarten. Yale: Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Mellon MS 136 (1798; Johann Haussen scripsit); Adnotationes Hermeticae, Fasciculus III. Vienna: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. Ser. n. 4135 Han (c.1780-1799; Teofil Kelíni scripsit), pp. 1-50.

[4] Cf. Heinrich Khunrath, De igne Magorum philosophorumque secreto externo et visibili (Strasbourg: Zetzner, 1608), pp. 70-72.

[5] An extract from an unpublished work of ‘Herverdi’ is given in the first book of the Darmstadt and Stuttgart manuscripts (MS Darmstadt, 46-47); Herverdi’s Erklärung des mineralischen Reichs (Berlin: Arnold Wever, 1783), pp. 36-37, supplies an extract from Das Buch der Weißheit from the fourth book of MS Stuttgart (MS Stuttgart, 279-280), and promises to reveal more in a manuscript he possesses (which is presumably either the Thesaurus thesaurorum or his own work cited in its first book). A redactor of MS Stuttgart inserts prolonged accusations of impropriety against ‘J. C. Vanderbeeg’ for printing Das Buch der Weißheit (an early order text: cf. MS Hamburg, 20) whilst omitting its essential passages; the same redactor proceeds to supply those passages in MS Stuttgart (pp. 275 ff.). In the preface to Erklärung des mineralischen Reichs, f. 2 verso, the editor states it was never Herverdi’s intent to publish this work; yet on p. 37 Herverdi advertises his possession of restricted knowledge by stating he may not say more in print. Hence Herverdi was a contemporary of the publisher, with whom he collaborated. See I. C. von Vanderbeeg, Manuductio Hermedico-philosophica (Hof: Johann Ernst Schultz, 1739), pp. 234-277; the fact the redactor refers to the second edition (c.1750) of this book supplies a rough terminus post quem for MS Stuttgart.

[6] MS Octagon, II, 7-8; MS Stuttgart, 153-158; MS Darmstadt, 138-143; Michael Toxites, Onomastica II (Strasbourg: Bernhard Jobin, 1574), pp. 410-412; Jacobus Tirinus, In universam Sacram Scripturam commentarius, vol 2 (Venice: Nicolai Pezzana, 1760), Index I, p. iii.

[7] MS Stuttgart, 158; MS Darmstadt, 143.

[8] MS Octagon, II, 7; MS Stuttgart, 157; MS Darmstadt, 142. MS Octagon, III, 45-66, conforms to the chapter order of MS Darmstadt, 312-344, not MS Stuttgart; hence it is not derived from MS Stuttgart.

[9] Thus the related group of ‘animal tinctures’ made from blood, urine and sweat are numbered one to three in MS Darmstadt, 346-363; in MS Octagon, III, 73-81, the blood tincture is omitted, as is the numbering for the other two tinctures.

[10] Hence the sub-titled ‘Iuramentum Fraternitatis’, MS Octagon, I, 29; cf. Arthur Edward Waite, The Brotherhood of the Rosy Cross (London: William Rider & Son, 1924), pp. 70, 634.

[11] Johann Christoph von Woellner, Der Signatstern oder die enthüllten sämmtlichen sieben Grade der mystischen Freimaurerei nebst dem Orden der Ritter des Lichts, vol 2 (Berlin: C. G. Schöne, 1803), pp. 114, 117. The primary ingredient of the incense is mandrake; the Holy of Holies and other fixtures are illustrated in the Octagon’s Asiatic Brethren manuscript tables for the first main grade rituals, Ad 1ste Hauptstuffe Nr. 1 + Nr. 3 (c.1786); cf. Die Brüder St. Johannis des Evangelisten aus Asien in Europa, oder die einzige wahre und ächte Freimaurerei (Berlin: Johann Wilhelm Schmidt, 1803), pp. 208 ff.

[12] MS Hamburg, 9-10; MS Dresden, 3-4; MS Vienna, 4-5.

[13] Thus both the Thesaurus thesaurorum and the Testamentum instruct initiates to show only the laws of the fraternity and the Buch der Weißheit (cf. infra) to a potential candidate; and as even these tracts allude to higher secrets, care should be taken lest ‘the seal is broken prematurely’, the candidate leaves and restricted knowledge is profaned.

[14] MS Vienna, 248: ‘…habe bey der handt eine Kugel, so aus der Electrum gegossen, wie wir dir solches gelehret in der Magia Divina’. Magia divina die Gott der Herr nur seinen Kindern vorbehalten hat, worinnen unaussprechliche Wunder zu sehen, von Wort zu Wort beschrieben. Dresden: Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden, MS N 166, pp. 167-197 (1728); I. N. R. I. Magia divina, die Gott der Herr nur seinen Kindern vorbehalten hat, worinnen unaussprechliche Wunder zu sehen, von Wort zu Wort beschrieben. The Hague: Bibliotheek van de Orde van Vrijmetselaren, MS 240 A 43 (1730); De magia divina oder Caballistischer Geheimnüsse. London: Wellcome Library, MS 4808, pp. 223-263 (1737); Kabbalistische Geheimnisse de magia divina worinnen allerhand rare unerhoerte Dinge enthalten. Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Kiesewetteriana 18 (1767); published as Magia divina, oder gründ- und deutlicher Unterricht, von denen fürnehmsten Caballistischen Kunst-Stücken derer Alten Israeliten Welt-Weisen, und Ersten, auch noch einigen heutigen wahren Christen (s.l.: L. v. H., 1745), a rare work also held at the Octagon.

[15] MS Octagon, II, 22: ‘…habe bey der hand eine Kugel, so aus dem Electro seu Wismutho gegossen ist’; MS Darmstadt, 155: ‘…habe bey der Hand eine Kugel, so aus dem Electro im ersten Theil dieses Buchs gegossen worden’; in this manner the scribes refer to electrum not as an alloy of the seven metals (electrum magicum) but rather as bismuth, i.e. the mineral referred to in the first book of ThQ1 (cf. MS Darmstadt, 106). This is a reference to electrum as a mineral ‘full of seminal power’: Paracelsus, Werke, vol 5, ed. Will-Erich Peuckert (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1968), p. 415.

[16] Pseudo-Paracelsus, ‘Dei [sic] magia oder magia divina seu praxis Cabulae albae et naturalis’, in Septimus sapientiae: Liber verus ac genuinus. Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Kiesewetteriana 1 e (1778), pp. 426-572 (pp. 567-568).

[17] R. Abrahami Eleazaris Uraltes Chymisches Werck, 2 vols (Erfurt: Augustinus Crusius, 1735).

[18] Pseudo-Thölde, Schrifftliche Unterrichtung der wahren Weißheit von der F. R. C. London: Wellcome Library, MS 4808 (1737); apparently this text was translated from the French (see the notarial attestation on the verso of the last leaf) and was subsequently split into two parts for publication as pseudo-Thölde, J. G. Toeltii, des welt-berühmten Philosophi Coelum reseratum chymicum (Erfurt: Carl Friedrich Jungnicols hinterlassene Wittwe, 1737) and Magia divina (1745, cf. n. 14 supra). The preface from ‘Johann Carl von Frisau, Imperator’ in Wellcome Library MS 4808 includes a passage (p. 6) on the Urim and Thummim that is excised from the printed Coelum reseratum chymicum, ff. 8 recto – 8 verso.

[19] Pseudo-Trithemius, Himmlisches und übernatürliches Geheimnis des Geistes und der Seele der Welt und von der natürlichen Magia. Amsterdam: Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica, MS M 217; pseudo-Trithemius, Heimliches und uebernatuerliches Geheimnis des Geistes und der Seele der Welt, 1506. Überlingen: Leopold-Sophien-Bibliothek, MS 234; the latter text is closely related to Scheible’s printed edition: Wunder-Buch von der göttlichen Magie, ed. Johann Scheible (Passau [Stuttgart]: [Johann Scheible], 1506 [1857]).

[20] γνῶθι σεαυτόν seu noscete ipsum: Sextus sapientiae liber verus ac genuinus. Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS Kiesewetteriana 1 d (1777); the title of this manuscript comes from its first chapter, which corresponds with that of MS Stuttgart, MS Darmstadt and the Testamentum (‘Erkenne dich’).

[21] Cf. Hereward Tilton, ‘Of Electrum and the Armour of Achilles: Myth and Magic in a Manuscript of Heinrich Khunrath (1560-1605)’, Aries: Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism 6, 2 (2006), pp. 117-157.

[22] Cf. Hereward Tilton, ‘Of Ether, Entheogens and Colloidal Gold: Heinrich Khunrath and the Making of a Philosophers’ Stone’, in Aaron Cheak (ed.), Alchemical Traditions: From Antiquity to the Avant-Garde (Melbourne: Numen Books, 2013), pp. 355-422; see also Khunrath, De igne Magorum, 89-90: the ‘URIM Theosophorum’ is created ‘Physico-Chymicé, divino Magicé, Et Christiano-Kabalicé’ from the ‘IGNIS Naturae internus Catholicus’.

[23] Pseudo-Paracelsus, Dei magia, 568.

[24] Schrifftliche Unterrichtung, 235; cf. Khunrath, De igne Magorum, p. 90: the ‘IGNIS Naturae internus Catholicus’ (i.e. ether) used to create the Urim is also the fuel for ever-burning lamps.

[25] Schrifftliche Unterrichtung, 232.

[26] Pseudo-Paracelsus, Dei magia, 567-568, 569.

[27] Schrifftliche Unterrichtung, 233-234; the conception of the Urim and Thummim as brightening or darkening gemstones is to be found in the work of Augustine and other Church Fathers: Cornelis van Dam, The Urim and Thummim: A Means of Revelation in Ancient Israel (Warsaw: Eisenbrauns, 1997), pp. 27-28.

[28] MS Octagon, 28-29; MS Vienna, 37; MS Dresden, 36; MS Hamburg, 33.

[29] Von Woellner, Johann Christoph. Johann Christoph von Woellner to Johann Rudolf von Bischoffwerder, 22 April 1783. Berlin: Geheime Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, BPH Rep. 48 – König Friedrich Wilhelm II, Nr. 8, Bd. 1, ff. 2o recto – 21 recto (f. 20 recto). In the previous year the prince had reached the penultimate eighth grade (Magister): Johannes Schultze, Forschungen zur brandenburgischen und preussischen Geschichte (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1964), p. 254.

[30] Heinrich Khunrath, Consilium de Vulcani magica fabrefactione armorum Achillis Græcorum omnium fortissimo et cedere nescii. Stockholm: Kungliga Biblioteket MS Rål 4 (1597).

[31] Heinrich Khunrath, Amphitheatrum sapientiae aeternae (Hanau: Erasmus Wolfart, 1609), p. 204.

[32] Tabulae theosophiae Cabbalisticae. London: British Library, Sloane MS 181, ff. 1 verso – 2 recto; cf. Peter Forshaw, ‘“Behold, the dreamer cometh”: Hyperphysical Magic and Deific Visions in an Early Modern Theosophical Lab-Oratory’, in Joad Raymond (ed.), Conversations with Angels: Essays towards a History of Spiritual Communication (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 175-200 (pp. 184-186).

[33] An expression of the notion that the psalms exert magical power over spirits: hence a Psalterium magicum is bound together with the Dresden Magia divina (cf. n. 14 supra).

[34] Khunrath, Consilium, 43; the origins of the electrum magicum bells are to be found in pseudo-Paracelsus, Archidoxis magica, in Paracelsus, Sämtliche Werke, vol 14, ed. K. Sudhoff (Munich: Oldenbourg, 1933), pp. 437-498 (p. 488); the same tradition is described in (e.g.) De magia divina, Wellcome MS 4808, 244-248.

[35] Hence Tabulae theosophiae Cabbalisticae, f. 1 verso: ‘…diese der GOTTHEIT geheiligte Ahnbedeutungs Zeichen…’

[36] Edward Scott, Index to the Sloane Manuscripts in the British Museum (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1904), p. 90 (cf. p. 289) dates it to the seventeenth century, while Samuel Ayscough, A Catalogue of the Manuscripts Preserved in the British Museum Hitherto Undescribed, vol 2 (London: John Rivington, 1782), p. 880, dates it to the sixteenth; the chirography and the interior design of the theosopher’s house suggest a slightly later date than the related oratory emblem of the Amphitheatrum (which was engraved in 1595), but still possibly within Khunrath’s lifetime.

[37] George Ernst Aurelius Reger, Gründlicher Bericht auff einige Fragen (Hamburg: Georg Wolff, 1683), p. 76: ‘…ich habe auch in meiner Jugend gemeint bey dieser Huren grosse Weißheit zu finden/ aber ich fand nur der Schlangen Klugheit/ welche ich als bittere Galle wieder hab müssen ausspeyen.’

[38] Johann Moller, Cimbria literata, vol 1 (Copenhagen: Orphanotrophius Regius, 1744), p. 494.

[39] Gottfried Arnold, Unpartheyische Kirchen- und Ketzer-Historie, vol 2 (Frankfurt am Main: Thomas Fritsch, 1700), p. 655; Sünne Juterczenka, Über Gott und die Welt: Endzeitvisionen, Reformdebatten und die europäische Quäkermission in der Frühen Neuzeit (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008), p. 96. Quakers faced persecution as ‘separatists’ (vis-à-vis corrupted ecclesiastical and secular power structures) and inspirationists (or Schwärmer, to use Luther’s derogatory term). Thus another Quaker in Pfeffer’s circle, Peter Arend, was banished from Halle in 1663: Gottfried Olearius, Halygraphia topo-chronologica (Leipzig: Johann Wittigau, 1667), p. 488; this fact contradicts the counter-assertion in the supplement to Gottfried Arnold’s Fortsetzung und Erläuterung… der unpartheyischen Kirchen- und Ketzer-Historie (Frankfurt am Main: Thomas Fritschens sel. Erben, 1729), p. 1271, that Pfeffer and Arend ‘were never Quakers’.

[40] Breckling graduated from the University of Strasbourg in the same year (1655) as another member of the Holstein Quaker circle, Johannes Grimmenstein; both men were from Flensburg. Die alten Matrikeln der Universitaet Strassburg 1621 bis 1793, vol 1, ed. Gustav Carl Knod (Strasbourg: Karl J. Trübner, 1897), p. 623.

[41] Friedrich Breckling, ‘Mehrere Zeugen der Wahrheit’, in Arnold, Fortsetzung und Erläuterung, 1089-1110 (p. 1098).