Foundations in Esoteric Systems, Teachings, and Orders

With the amount of information at our fingertips today, it seems we’re not limited by our ability to discover things, as much as our ability to use critical judgment and formulate the right questions to understand what we’re looking at. While we can easily find materials related to things like lineages, manuscripts, diagrams, processes, texts, and more, shedding meaningful light on these involves work, praxis, and developing experience. Through such development, perhaps we may even contact something more ageless and revealing our connection to the foundations and traditions of the past. Doing so might help us see that in many ways we exist not in a vacuum, but in a continuum, with the knowledge and work of those having come before left as an inheritance.

Over time, the teachings of esoteric traditions have varied in approach and emphasis, however, key themes revealing their core principles remain intact. Their discovery involves not only the research of texts but an understanding their methodologies; focused on what their work was meant to accomplish.

The Purification of the Soul in Patterns of Initiation

Looking to the work of many Western initiatic systems, there’s a common thread related to the development and purification one’s soul (sometimes referred to one’s subtle anatomy), to bring about harmony and qualities sympathetic with the divine. Whether we’re discussing the removal of undesired vices, the refinement of the personality through the humors, or even the early stages of alchemy, there is the suggestion of our natal emergence bearing a fragmented or unbalanced soul.

The soul has received numerous definitions over time, many related to Platonic, Christian, Eastern, Kabbalistic, Heremetic or Gnostic ideas in the Western Esoteric Traditions. Some correlate the Soul with the centers of thought and emotion, while others consider it more close to the Jungian concept of personality or character. Some equate the closest part to us with the astral sphere and others as a sphere of animation, or a vehicle that, through its purity is capable of ascending to higher, noetic realities.

According to Plato in his Republic, the soul is comprised of three parts: logos, thymos and eros. For Plato, the logos relates to nous and reason. Thymos corresponds with emotion and spiritedness. Eros relates to desire, or, one’s appetitive nature. Further exploration might see these as corresponding in some way to the four elements.

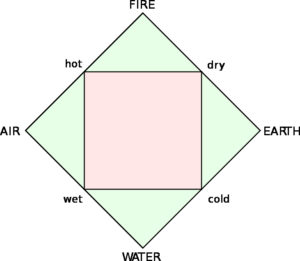

The best place to discuss the four elements is with Empedocles. Empedocles’ 4 elements was used to describe what the world is made from; qualities related to fire, air, water and earth. According to Empedocles, the elements (what he called “roots”) rested under the jurisdiction of Zeus, Hera, Nestis and Hades, respectively.[1] Furthermore, all beings, all souls and all matter were made up of these elements in various proportions. These proportions were dependent on the amount of forces of Love and Strife within them. These forces—of love and strife—relate to powers of attraction and repulsion.

To emphasize the relationship of these forces with the soul, its important to point out that the elements as such were not just though about in terms of their materiality, but also in terms of their influence over specific qualities of nature; no less physical, however, lighter, as virtues. Aristotle’s move in this direction can be shown by looking at such qualities in relationship to their elemental root. For example, Fire is dry and hot. Air is wet and hot. Water is wet and cold. Earth is dry and cold.[3]

In this manner, each quality can be thought of as a pole placed on one corner of a 4-pole “magnet”. The harmony of the four could be thought of as a state of “equipoise”, whereby the constituent elements have been acquired, expressed, and measured in equal proportion; establishing stability within their co-influence of virtues. [3]

Turning back to Aristotle, he also introduces the idea that the sensible qualities of these elements conjoins the physical with the invisible realm in a very specific way. In his Metaphysics, he says, “all organs, in all instances of perception, always come to exemplify the sensible qualities they perceive”.[4] According to this line of thought, that which is physical and penetrable by perception can come to emulate the virtues of the elements in their sensible form. Here, a clear relationship between the physical and invisible (albeit sensible) worlds takes place.

Furthermore, since such sensible qualities are related to the physical world, and thus the body, they also correspond to the soul. This is because the relationship between the body and soul is integral, with divisions of the body corresponding directly to parts of the soul. As Aristotle explains in his De Anima, “the soul is the form of the body in much the same way the form of a house structures the bricks and mortar from which it is built.”[5]

Taking Aristotle’s influence forward, its along these lines that Hippocrates of Kos (once dubbed “the Asclepiad” by Plato and thus named after Asclepius, the God of healing) had devised a system of medicine. This system eventually evolved into the concept of humorism [6]. Hippocrates’ humorism diagnoses four temperaments (or humors) that are either abundant or deficient within the constitution of the individual. The humors were thought to be indicated through fluidic substances of the body known as: black bile, phlegm, yellow bile and blood. According to humoral philosophy, individuals possessing a nearer-to-equal proportion of the humoral substances were more prone to expressing greater intelligence and keeping to more pure perceptions.[7]

Similar to Empedocles’ concept of proportions of love and strife in the elements, Hippocrates posited that the near-equal proportions of the four humors as temperaments in an individual’s character produced an individual in good health. However, an imbalance—or a dyscrasia—of these corresponding four temperaments were thought to be the cause of all diseases in the body. Thus, diagnosing a person’s health was determined through assessing the expression of the temperaments through one’s character, evidenced through the four humoral substances. The temperaments were identified as the melancholic (corresponding to black bile), phlegmatic (to phlegm), choleric (to yellow bile) and sanguine (to the blood). One might also relate these to the elements of Earth, Water, Fire and Air elements, respectively.

A person suffering from a certain affliction could thus be diagnosed by looking to the disproportionate relation of temperaments in their constitution or character (corresponding to the balance or imbalance of their fluidic substances). Restoring health to the person might thus involve balancing these temperaments with their corresponding elemental virtues. This might be achieved through adjusting character, or, in the case of some theorists, through the beneficial influence of food, drink, or music. In other words, by affecting and transforming the temperament of the character, the balance of one’s physical health could thus be influenced.[8]

According to Galen of Pergamon, a Roman physician and proponent of humorism in the 2nd century AD, the humors were also prone to influence from “non-naturals”—unnatural movements caused by distortions in man’s innate tendencies, otherwise described as “passions or perturbations of the soul”[8a]. Thus to restore the balance of the soul, one must purge themselves of these unnatural perturbations that are connected to the temperaments of individual.

For discussing the development of virtues in relationship to the soul, we must discuss Plato. In The Republic, Plato describes a system of order that governs both the Just City as well as the Just Man. The Just City is structured into three classes: the producers, the auxiliaries, and the guardians. Correspondence to these classes of the city, in the Just Man, the soul is divided into three parts: the appetitive, the spirited and the logical. To bring harmony between these separate social classes and parts of the Soul, a series of four cardinal virtues are prescribed. These are Courage (Fortitude), Temperance (Moderation), Wisdom (Prudence) and Justice.

In Plato’s application of the virtues to the classes and divisions of soul, Temperance is prescribed for the appetitive and the producers. Courage is applied to the spirited and the auxiliaries. Wisdom is used for the logical and the guardians. The final virtue, Justice, stood in its own class—emerging out of, as well as ruling over—the proper harmony of the other three.

A relationship between the 4 elements and the soul becomes perhaps most clear in Plato’s Timaeus. There, the elements—in various divisions of difference, sameness and being (i.e. identity)—are used to create both the World Soul and the human soul. The World Soul (i.e. of the universe) is considered the ordered harmony of all creation, and that which is made manifest by the benign, loving demiurge. The human soul, on the other hand, although said to be comprised of the same substance as the World Soul, is considered less pure since it was made of but a fraction of what remained after the universe was formed. In other words, in the human soul, difference, sameness and being also exist, but they appear there less harmonious than in the World Soul.

Thus the World Soul and human soul are somewhat reflective of one another, essentially as macrocosm and microcosm. However, they exist in a different hierarchy of order in terms of their different states of harmony (that is, at least in terms of one’s natal state). This is somewhat similar to how the classes of society in Plato’s Republic reflect the different parts of the individual soul. There is a pattern seen in Plato where the soul of the individual corresponds with the social order, and perhaps the social order with the cosmic order. Such concepts might give us important clues about the purposes behind the ordering of the stages of initiation, as we will next explore.

In each example, a general premise appears consistent; that in its native state, the human soul or character arrives inherently unbalanced and out of harmony with the divine order of nature or the cosmos.

The Work of the Soul in the Outer Orders, the Lesser Mysteries?

The fractured, fallen, or inharmonious state of the soul is an idea that appears time again in the Western traditions. If we extend this definition to include developing the state of one’s character, one’s emancipation from restricting influences, or even banishing sin, this approach can be expanded even further. In biblical terms, for example, we find the temptation and fall from Eden. In several ancient myths, we find a struggle between one’s animal nature vs. society or nature. The whole of alchemy is dedicated to multiple states of purifying and perfecting substances for their eventual reintegration. In Freemasonry, there’s the rough ashlar that needs to be worked on to become the perfected ashlar. And so on. In each example, a general premise appears consistent; that in its native state, the human soul or character arrives inherently unbalanced and out of harmony with the divine order of nature or the cosmos.

From a classical perspective, another way to read it might be that a person with an unbalanced influence of the elements or temperaments is subject to the whims and fluctuations of the “lower” mental or emotional vehicles or passions. Until bringing these into accord, one is thus controlled by fleeting external, rather than eternal and internal causes.

Carrying this perspective forward into the present, we could look to Rosicrucianism as reflecting such principles. Because of its relationship with Hermetic philosophy (in the sense of a microcosmic and macrocosmic relationship, as well as a divine union), and with its reformation aims, it might seem apt to consider the role of the soul not only in relation to the individual character but also with respect to the relationship with the forces of nature. Ideally, the harmony of nature would thus become reflected in the individual, as well as in the overall social harmony. These are ideas present in the Manifestos. Perhaps not all groups or teachings appear to use the very same model, but if we look more closely, perhaps we can identify a familiar pattern or language being used on either an individual or social scale.

Take the Golden Dawn, for example. Its system has four elements that are placed or integrated into the sphere of sensation of the candidate. These also comprise the first four grades (not including Neophyte) of the outer order. The passing from the first to the second order thus occurs when the four elements have been integrated into grade ritual as well as in personal practice, as is outlined in grade meditations and knowledge lectures. If we accept at face value that the four elements of the outer order of the GD are meant to be purified within the Ruach of the candidate, then by affiliating the Ruach with not only the individual soul, but also Yetzirah (i.e. the world of formatin) we could be more certain of speaking of the same pattern as found in the humors, virtues and the elements of the soul in relationship to a particular level of the cosmic order.[9]

Furthermore, one might consider how three of the classical virtues spoken of by Plato follow cards of the Major Arcana of the post-Waite/Smith Tarot. These are Temperance, Justice and Strength (with Strength representing the virtue of Fortitude). Considering that the virtue of Temperance marks the path moving from the outer order to the inner order of the GD (the other two apply to paths of the second order), we might consider here the movement of the candidate from the appetitive part of the soul to the spirited part of the soul. In the Portal grade, the left and right paths to Tiphareth are blocked for the candidate (represented by The Devil and Death cards). The aspirant must work through the middle.

For the Martinists, a mask is worn to represent the identity, personality and temperament of the individual character. It’s been said that by donning the mask, the initiate’s personality is concealed while s/he becomes “an unknown among unknowns”. The role of anonymity would appear to represent a liberation from the outer personality, personal passions and the trap of vanity:

“We who are assembled here care not for the recognition, honor, or distinction the world may have conferred upon us and by which we are known to it. These things are of the outer personality and the mask conceals them from ourselves and others so that nothing may distract us from the light we seek.”[10]

In the Martinist S.’.I.’. degree, the candidate is further tested on their understanding of the mask’s symbolism. In this degree, the candidate is required to present a special dissertation after which s/he will wait in silence while their peers question and scrutinize their work. Should the candidate demonstrate or express any sign of anger, they are deemed to have failed and unable to pass into the second temple. [11]

Clearly, this is a test of the candidate’s patience, self-control, and temperance of their lower passions. Again, the concept relates to the character of the individual and fostering of virtues over succumbing to rash perturbations. Further along these lines, in the 5th and 6th degrees of the Chevaliers Bienfaisants de la Cité-Sainte (CBCS) of Willermoz’s Rectified Scottish Rite, the four classical virtues are in fact stated as goals for the candidates. Justice is called to reign in the heart, Temperence to govern the tongue, Prudence to inspire one’s actions, and Fortitude (referred to as Strength) for guiding personal conduct.[12]

That such ideals are present in the language and work of Masonry, then, hardly appears as a surprise. While Freemasons have their “peculiar system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols”; many of these deal with truing, leveling, squaring, balancing, and polishing. That the rough and polished ashlars are accepted as representations of the candidate’s character appears at the center of this inquiry of purifying the soul. The subjects of morality (correct self-acting) and ethics (correct social action) play significant roles in this symbolism and are yet another clue to the nature of the work of a Freemason.

Recent teachers of magic, like Franz Bardon, spoke about the humors and elements in the form of a “tetrapolar” magnet. This four-poled magnet might be visualized as the four-pointed compass of the elements. In his Initiation Into Hermetics, Bardon instructs the initiate to work on elemental aspects of the humors directly, by reflecting upon each through a Soul Mirror. This process identifies the influence of the humors within the individual, where one’s unconscious and subconscious tendencies are brought to light. By carrying through with this process, one enters into a state of equipoise, which, as Bardon explains, is required before any magical work. Without this balance or purification of the elements—i.e. working on the Soul—the initiate is otherwise exposed and unprotected from potentially harmful psychological or spiritual beings.

In each of the above examples, the qualities of the character, the temperament of the soul, and the sensible forms of the elements are considered as real and affective substances. Though subtle, they are approached as shapable and transformative in the sense of their influence on the individual—both within the soul as well as the physical being. As Josephine Peladan once stated, “…I will say without fear: That which manifests the external form of an idea, will realize its internal essence…equally, the internal essence can bring forth an adequate external form.”

Other concepts that represent these ideas appear in Western Esotericism.

In his Oration of the Dignity of Man, Pico della Mirandola states: “The Paradise of God is bathed and watered by four rivers; from these same sources you may draw the waters which will save you”. Here it seems we are looking at another pattern relating to the 4 elements and the soul. As St. Ambrose had once put forth:

“We read of a fountain and a river which irrigates in Paradise the fruit-bearing tree that bears fruit for life eternal. You have read, then, that a fount was there and that ‘a river rose in Eden,’ [ Gen 2:10 ] that is, in your soul there exists a fount“.

As implied, the four rivers flowing out of Eden originate from a single source; this source is a fountain.[13].

Other Examples

In Lurianic Kabbalah, the rectification of Olam HaTohu (The World of Tohu: Chaos/Confusion) into Olam HaTikun (The World of Tikun: Order/Rectification) reflects the purifying of the soul as well (in addition to a more worldly reformation) with the goal of evolving each level of the soul towards a higher and more pure state. [14]

In Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa’s Three Books of Occult Philosophy, he states that the attainment of wisdom proceeds through the work of “merit” (dignitas meritoria), and this requires moral and intellectual training. He explains that through the overcoming of corporeal passions and one’s sense impressions, a recovery of knowledge ensues. One’s soul then becomes a “soul standing and not falling” (anima stans et non cadens) which is able to perform miracles “by God’s virtue” (in virtute Dei). [15]

The ancient Orphic rituals were involved with directing the influence of catharsis to affect the soul; to purify it or “purge” it of unnecessary perturbances. [16]

The Chivalric codes of the Grail of the Knights dealt with moral codes, ethics and the management of their lower passions to express higher ideals such as romance, fidelity, and honor. [17]

Marsilio Ficino adopted the Platonic model of ascension via the purification of the soul and separated the virtues into 2 types: Moral Virtues and Intellectual (or speculative) virtues. Moral Virtues are those that, when expressed through routine and habit, release the Soul from the dictating needs of the bodily senses while governing desires and appetites. The Intellectual (or speculative) virtues are those which govern the world of forms: the divine, knowledge of nature and the craftsman’s ability to produce artifacts. [18]

Conclusion

It’s often been said that the profane (ie the impure) are prevented from entering the inner sanctuary of the temple. With this, perhaps we have a better sense of what was meant by this. With respect to the teachings of the orders and sages over time, it seems clear that many share this wisdom in common. Before the inner order, or before performing divine or magical work, the Soul should first be stripped of its lower urges and imbalanced tendencies and purified.

New readers, don’t forget to sign up to our blog to read other more interesting articles just like this. We’ll never send you marketing emails. Just a quarterly update on the most recent top post. Sign up if you love this reading and Pansophers!

[1] See: Sextus Empiricus, Against the Mathematicians, section X: Against the Physicists

[2] Found in Aristotle’s On Generation and Corruption

[3] Franz Bardon’s Initiation Into Hermetics is a good example of this idea, his “tetrapolar” magnet involving the 4 elements is an excellent practice in this regard

[4] Shields, Christopher, “Aristotle’s Psychology”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/aristotle-psychology/

[5] ibid

[6] Hippocrates, Hippocratic Corpus, On The Sacred Disease.

[7] Kingsley, K. Scarlett and Parry, Richard, “Empedocles”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/empedocles/

[8] A good source for such remedies is Marsilio Ficino’s Three Books on Life. His work is influenced by many philosophers of the classical age, but is a good summary of many such concepts in the vein of Pythagoras, Galen, or Orpheus.

[8] Galen’s Six Non-Naturals,”Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 44 (1970): 372-377.

[9] Refer to John Frederick Charles Fuller’s Golden Dawn notes transcribed in 1906 and 1907 from the personal copies of Allan Bennett, held in the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, as referred to: https://hermetic.com/gdlibrary/the-nature-structure-and-role-of-the-soul/the-sphere-of-sensation

[10] From “The Martinist Pentacle”: https://themartinistpentacle.wordpress.com/category/symbols/

[11] Stichting Argus: http://www.stichtingargus.nl/vrijmetselarij/martiniste_r3.html

[12] Stichting Argus: http://www.stichtingargus.nl/vrijmetselarij/s/rsr_r5.html http://www.stichtingargus.nl/vrijmetselarij/s/rsr_r6.html

[13] Hexameron, Paradise, and Cain and Abel (The Fathers of the Church, Volume 42)

[14] for example, summarized on Chabad-Revisited: http://chabadrevisited.blogspot.com/2012/12/tohu-tikun-and-divine-imperfection.html Read Leonora Leet, The Kabbalah of the Soul: The Transformative Psychology and Practices of Jewish Mysticism offers a more thorough explanation.

[15] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, section on Agrippa: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/agrippa-nettesheim/

[16] Catharsis: On the Art of Medicine, by Andrzej Szczeklik offers some discussion on the purifying effect of music and dramatic art.

[17] The 7 Knightly Virtues of Courage, Justice, Mercy, Generosity, Faith, Nobility and Hope are similar to other virtues such as the Cardinal Virtues and the 7 Theological Virtues and can be considered all much for the same purposes.

[18] A summary of Ficino’s theory of ascension with the Moral and Intellectual Virtues can be found on The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: https://www.iep.utm.edu/ficino/