According to his successor, Émile Dantinne, Joséphin Péladan’s L’Ordre de la Rose+Croix Catholique et Esthétique du Temple et du Graal had three patron saints for its three degrees:

“Leonardo da Vinci in whose name neophytes took the oath of the first degree, Dante Alighieri, in whose name they swore for the second degree, and Saint John and the Holy Spirit for the final degree of Commander.”[1]

The second degree of Chevalier, as an esoteric knighthood in which initiates swore by the name of the medieval Florentine poet Dante Alighieri, is especially linked to the Knights Templar, of which Péladan claimed a true filiation through his brother Adrien. As is well known, Péladan’s own order existed under the triple banner of the Rosicrucians, the Templars, and the Grail Mysteries.

But why, during this second degree, swear by the name of Dante, rather than a more well-known Templar figure like Jacques de Molay? The answer lies in Péladan’s belief in the esoteric interpretation of Dante, first espoused in the mid-nineteenth century by Gabriele Rossetti and Eugéne Aroux, taken up by Péladan and incorporated into his Rosicrucian order, and later restated not only by other esotericists, like René Guénon in his books The Esoterism of Dante and Insights into Christian Esoterism, but by mainstream writers like the Modernist poet Ezra Pound.

These writers and esotericists believed that Dante’s circle of Italian poets, the Fedeli d’Amore, was in fact an initiatory order of mystic chivalry, centered around the divine feminine (embodied, for Dante, in the figure of Beatrice). They often saw a filiation for this order in the related movement of French troubadours, and ultimately in the Gnostic Cathars, perhaps the quintessential medieval heresy. “Amor,” the watchword of the Fedeli — the poet’s chivalric love of the high-borne Lady and the subject matter of his lyrics — was seen as a heterodox Cathari reversal of the word “Roma,” symbolizing the orthodox doctrines of the Roman Church.

But Péladan didn’t stop there. Ultimately, he believed that the Cathars, the French troubadours, the Italian Fedeli d’Amore, the German minnesangers, the skalds in Norway, minstrels in Wales, the Knights Templar, and finally the Grail Knights of medieval Arthurian romance all constituted one continuous tradition deriving — if you go all the way back — from Plato, Orpheus, and the Eleusinian Mysteries, an initiatory chain stretching from antiquity to the Middle Ages, and thence to the Renaissance and to the Occult Revival of Péladan’s own day. As he writes in Le Secret des troubadours:

“If one studies the hidden meaning of medieval literature, the Renaissance no longer appears to be a sudden resurrection of the ancient world.

Neoplatonism had already penetrated our tales of adventure, and when it showed itself openly under the Medicis it was because they assured it effective protection against the Roman Inquisition.

Gemisto Plethon and Marsilio Ficino are the official teachers of old Albigensianism, as Dante is its prodigious Homer.

Fiction and history correspond with a striking similarity on this subject: do not the knights Templar represent in reality the Grail Knights, and does not Monsalvat have a real name, Montségur? …

The heretics, then, become troubadours in Provence, and ‘trouveres’ in the north, guillari, men of joy in Italy, minnesingers in Germany, scales in Norway, minstrels in Welsh countries.”[2]

Amor, of course, relates ultimately for Péladan to the Platonic theories of Beauty and Love — in which, guided by Eros or desire, the philosopher moves from the love of the physical beauty of his beloved to the Love of the transcendental Beauty of the Ideal. As Liebregts summarizes in his book on Ezra Pound and Neoplatonism, the philosopher “must learn to see that such beauty of a particular individual is interchangeable with the beauty of many others. Therefore he will concentrate on the essence of all those beautiful human beings and contemplate what constitutes their beauty. Then this common denominator of all mortal beauty will be regarded no longer as bound to one person, but will be pursued in its Ideal Form, that which supplies the forms with its essence. Finally, the soul will ascend to a visionary knowledge of true Beauty itself.”[3]

Tracing the idea through history (and ultimately to Péladan and Pound), Liebregts quotes a beautiful passage from Plutarch, in which he describes the role of Eros in the ascent of the soul to transcendental Beauty:

“Love, who has come to it through the medium of bodily forms, is its divine conductor to the truth from the realm of Hades here; Love conducts it to the Plain of Truth where Beauty, concentrated and pure and genuine, has her home. When we long to embrace and have intercourse with her after our separation, it is Love who graciously appears to lift us out of the depths and escort us upward, like a mystic guide beside us at our initiation.”[4]

Now, Péladan contrasted the marriage rites of Roma, centered around procreation, with the Platonic, spiritual love of Amor: “In the provencal religion marriage meant obedience to Roman orthodoxy, and love meant adherence to the Occitane doctrine; such is the first key to all the love literature” (trans. Surette). The legendary lineage here from ancient Platonism, to the Cathar religion, to the love literature of the Middle Ages — and ultimately to Dante — is clear.

The Knights Templar seem like an aside in this lineage, but Dante (as well as the Cathars) was also often connected to the Templar Order. Many esotericists have suggested that he was an initiate or even a leader of a tertiary order of the Templars called the Fede Santa, whose dignitaries bore the title of “Kadosh” (familiar from the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry). This would explain why Dante chose St. Bernard of Clairvaux as his guide in the Paradiso, Bernard being the ecclesiastical founder of the Templar Order and the writer of its Rule.

In this connection, René Guénon summarizes the reflections of Aroux in his book on Dante, especially the links between Dante’s symbolism and the twenty-sixth degree of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, the Prince of Mercy or Scottish Trinitarian. Like many Masonic degrees, which are a hodgepodge of symbols, references, and vague remembrances of older esoteric traditions and independent orders, the Prince of Mercy ritual contains little of the esoteric theory that figures like Guénon would make explicit. But the degree does contain the basic symbols of the esoteric interpretation of Dante — the colors of the three theological virtues with which Beatrice is also draped in the Commedia, the symbolism of the numbers three and nine, the Most Excellent Chief Prince as the incarnation of Love or Amor with his arrow, and, above all, the statue of a virgin (an image of the divine feminine) as the palladium of the Order.

Thus for how writers like Péladan and Guénon have interpreted the esoteric lineage of Dante. But as we can see from Péladan’s use of an oath to Dante in his own Catholic Rose+Croix, he was not writing out of a merely scholarly interest in this tradition — he saw his own order as continuing this lineage, including the work of Dante, “its prodigious Homer.”

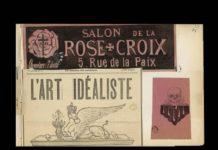

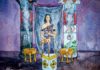

During the fin de siècle occult revival, Péladan would take the esoteric interpretation of Dante and overlay it with his own occult understanding of art and aesthetics. In Aman-Jean’s poster for the second Salon de la Rose+Croix in 1893, Beatrice is led away (to Heaven?) by an angel, while gazing at and passing a lyre to someone out of the frame — presumably Dante. Above, the symbol of the Rose+Croix surmounts the scene. Symbolically interpreted, the image combines the esoteric interpretation of Dante with the myth of Orpheus and his lyre (also dear to Péladan’s heart, and a common theme in the Salons), all under the auspices of the Rose+Croix.

In this interpretation, Beatrice is not just an earthly woman for whom Dante pined away. She is a manifestation of the divine Sophia, the Immaculate Wisdom with whom we must marry ourselves if we are to conceive the Divine Light (the Incarnate Logos or the Christ) within ourselves. Understood in this way, Dante’s paeans to Beatrice become hymns to Sophia, and his journey through the three realms of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven in the Divine Comedy in order to find Beatrice — like Orpheus’ journey to the underworld to reclaim his wife Eurydice — become an initiatory journey in three degrees, in a quest to encounter the divine feminine or Sophia.

According to Péladan’s aesthetic esotericism, it is the love of Beauty that allows one to recall one’s divine heritage and to reintegrate with God. As suggested by the Platonic lineage into which he inserts Dante, Péladan’s aesthetics follow the philosophies of Renaissance Neoplatonists like Ficino, Pico della Mirandola, and Bruno; he also traces his theories back to late antique philosophers like Plotinus and Iamblichus, and ultimately to Plato, Pythagoras, and Orpheus. God is transcendental Beauty and, though creation is fallen, traces of the divine Beauty remain in book of Nature — the Mirror of Wisdom or Sophia — to be discovered by the initiate of the mysteries. These traces, when pursued by the initiate, lead back up a ladder through the celestial hierarchies to God.

For Péladan, Orpheus provides the archetype of the artist-initiate, the ancient source of the esoteric intellectual lineage detailed here.[5] By using his artifice (which Péladan believed was taught to humanity by the fallen angels, a whole other side to Péladan’s teachings which we will have to explore another day) Orpheus was able to play celestial music on his lyre that would immediately bring its hearers back to their origin in the Divine. The traces of divinity in his music were so powerful that they even allowed Orpheus to charm Hades himself, temporarily allowing him to reclaim his wife Eurydice from the underworld.

Allegorically speaking, we have here a myth that suggests that art and aesthetics, when properly understood, allow the initiate to invoke the divine traces in creation, immediately reverting us to our heritage in God. This theurgical understanding of art was shared by Péladan, who in the Manifesto of the Salons de la Rose+Croix famously wrote:

“Artist, you are a priest: Art is the great mystery and, when your effort leads to a masterpiece, a ray of the divine shines down as on an altar … Artist, you are a magus. Art is the great miracle and proves our own immortality.”

This is why, in Aman-Jean’s image, the figure of divine Wisdom, Beatrice, hands over the lyre. The image suggests that though Sophia might be seemingly out of reach in a fallen or fragmented creation, through the medium of the lyre (art, music, and artifice) the artist-initiate might rediscover the traces or signatures of the divine Wisdom, and might recall his hearers into the presence of the Beatific Vision. (In this sense, the lyre here takes the place of the phallus in the myth of Isis and Osiris, or the sprig of acacia in the Masonic legend.)

Dante, then — interpreted through the aesthetic esotericism of Péladan — is revealed to be an artist-initiate who, through his poetry, is able to lead his readers on an initiatory journey to the place of the heavenly Beatrice or Sophia, the nine spheres of heaven in the Paradiso. Dante (and Péladan as his interpreter) is revealed to possess a sophianic mysticism based on the veneration of the divine feminine, which is attained through artistic-esoteric practice, through — in Dante’s case — divine poesis. Traces of Sophia are to be found all over the material cosmos; it is up to the artist-initiate, through artistic practice, to discover and concentrate them into initiatory forms. As Dante says in the final canto of the Paradiso, in an inchoate attempt to describe his vision of the Divine Light,

“O grace abounding and allowing me to dare

to fix my gaze on the Eternal Light,

so deep my vision was consumed in it!

I saw how it contains within its depths

all things bound in a single book by love

of which creation is the scattered leaves:

how substance, accident, and their relation

were fused in such a way that what I now

describe is but a glimmer of that Light.”[6]

Thank you Nicholas for this insightful blog post!

If you’re new to our blog, don’t forget to sign up to stay informed. We’ll never send you any marketing emails, just blog updates on top posts sent out every quarter!

[1] Sasha Chaitow, “Symbolist Art and the French Occult Revival: The Esoteric-aesthetic vision of Sâr Péladan,” Newtopia Magazine, 2014.

[2] Trans. Leon Surette, The Birth of Modernism, 127–128.

[3] P. Th. M. G. Liebregts, Ezra Pound and Neoplatonism, 64–65.

[4] Plutarch, Moralia, 764F–765A.

[5] For more on the Orphic influences on Péladan, see Sasha Chaitow, “Making the Invisible Visible: Péladan’s Vision of Ensouled Art,” Project AWE, 2015.

[6] Dante, The Divine Comedy Vol. 3: Paradise, trans. Mark Musa, 392–394.

Thanks for finally talking about >”All Things Bound in a Single Book by Love”: Dante,

Péladan, and Esotericism <Loved it!

Since most of the information about Peladan came from Sacha Chaitow’s work – why not ask her to contribute instead? That would be far more illuminating, and better scholarship too.